China Plans 3rd Trans-Himalaya Forum Near Contentious Arunachal Border, China’s Ally Pakistan, Mongolia And Afghanistan To Attend; The Escalating India-China Border Tensions

The ongoing border tensions between India and China have become a source of global concern since December 2022 when both nations witnessed renewed confrontations along their 2,100-mile-long disputed border, commonly known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC). These tensions have escalated despite earlier clashes, notably the deadly encounter in the Galwan Valley in June 2020, which marked one of the most perilous Sino-Indian border crises since 1967. In the current, China is set to convene the 3rd Trans-Himalaya Forum for International Cooperation in Nyingchi, Tibet, near the border of Arunachal Pradesh, a move that could further strain relations between Beijing and New Delhi. What is particularly striking about the current situation is the intense military build-up on both sides of the border, suggesting that both countries are strategically utilizing peacetime to enhance their logistical capabilities, potentially for future conflict scenarios.

China is set to convene the 3rd Trans-Himalaya Forum for International Cooperation in Nyingchi, Tibet, near the border of Arunachal Pradesh, a move that could further strain relations between Beijing and New Delhi.

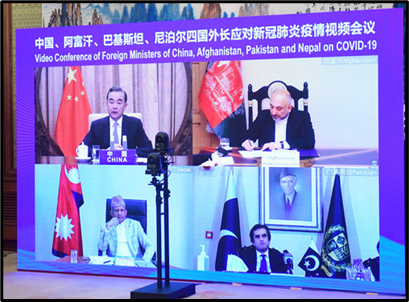

Pakistan’s acting foreign minister, Jalil Abbas Jilani, will be in attendance, potentially adding complexity to Sino-Indian ties, especially in light of China’s recent refusal to grant visas to athletes from Arunachal Pradesh for the Asian Games; at the same time, Mongolia and Afghanistan will also send representatives to the event, which is being held just 160 kilometres from Arunachal Pradesh.

The Pakistan foreign ministry released a statement stating that Foreign Minister Jalil Abbas Jilani was visiting China at the special invitation of Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi to participate in the 3rd Trans-Himalaya Forum for International Cooperation, scheduled from October 4th to 5th in Nyingchi, Tibet Autonomous Region.

The Trans-Himalaya Forum, launched in 2018, aims to enhance practical cooperation among regional nations on various topics such as geographical connectivity, environmental preservation, ecological conservation, and the strengthening of cultural ties.

The forum’s previous in-person meeting took place in 2019, and this year’s theme is ‘Ecological Civilization and Environmental Protection.’

During his stay in Tibet, Foreign Minister Jilani will deliver the opening ceremony’s address and hold meetings with several regional dignitaries, including the deputy prime minister of Mongolia, the foreign minister of China, and the interim foreign minister of Afghanistan, as per the Pakistan foreign ministry’s statement.

China India

Last month, India formally protested China’s selective denial of visas and accreditation to athletes from Arunachal Pradesh, characterizing it as a deliberate obstruction of sportspersons; hence, in response to China’s actions, India’s Union sports minister, Anurag Thakur, cancelled his attendance at the opening ceremony of the Asian Games.

In a controversial move, China claims Arunachal Pradesh as its own territory, referring to it as South Tibet; in August, China released a new map that incorporated Arunachal Pradesh and the Aksai Chin region in eastern Ladakh, drawing international criticism.

India, however, firmly rejects all of China’s claims regarding Arunachal Pradesh.

Escalating Tensions Along the India-China Border

Since December 2022, when confrontations between Chinese and Indian forces erupted once more along their contentious 2,100-mile border, known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC), tensions have continued to mount.

Previous clashes, notably the June 2020 conflict in the Galwan Valley that resulted in the deaths of at least 20 Indian and four Chinese soldiers, marked the most precarious Sino-Indian border crisis since 1967.

Both India and China are now deeply engaged in a frenetic competition to enhance their infrastructure along the border; the build-up suggests that both nations have strategically opted to utilize peacetime to bolster their logistical capabilities, potentially for future military conflict.

The Growing Sino-Pakistan Relations

The already delicate situation is further compounded by their increasingly assertive foreign policies, with issues like Sino-Pakistan relations and tensions surrounding the succession of the Dalai Lama; hence, the risk of escalation remains significant between these two nuclear-armed powers.

China’s Border Build-up

The LAC is roughly divided into three sections: western, middle, and eastern, while the western section encompasses Ladakh on the Indian side and Tibet and Xinjiang on the Chinese side.

The middle section runs through Indian states Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh and Tibet on the Chinese side. The eastern section includes Arunachal Pradesh, referred to as “South Tibet” by China, and Tibet.

It is the western and eastern sections are the most disputed and have seen the greatest militarization efforts; in Tibet’s western section, satellite images indicate a well-established Chinese presence.

Since 2017, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has ordered the construction of an extensive network of military installations to support the deployment of People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops.

China has resettled over 250,000 Tibetans closer to the border to cement Beijing’s territorial claims by creating “well-off villages” (xiaokang) equipped with housing, roads, public services, including supermarkets, schools, police stations, and internet or 5G connectivity.

These villages are part of the CCP’s broader “Plan for the Construction of Well-off Villages in the Border Areas of the Tibet Autonomous Region,” involving the construction of 628 villages in 112 Tibetan border towns, and by last year, construction had been completed for all villages.

Careful Planning By Chinese

While the exact locations remain undisclosed, India’s Foreign Ministry suggests that one such village in Arunachal Pradesh, in the LAC’s eastern section, lies 4.5 kilometers within India’s claimed territory.

These villages serve as a means for Beijing to assert territorial control, reflecting the CCP’s civilian-military fusion policy; the Tibetan herders work alongside PLA and CCP security units as plainclothes security operatives, forming “border patrol teams” conducting regular patrols.

The patrols are aimed at familiarizing PLA and CCP units with local conditions and routes. Chinese flags are placed in key locations when necessary to assert territorial claims, and ongoing recruitment drives in these villages further ensure a reserve of security personnel.

China’s increased presence near the LAC includes air bases, heliports, and air defense sites, all of which have more than doubled in number since 2017.

In the western section of the LAC, China is also investing in constructing a significant highway, G695, connecting Tibet and Xinjiang, which is slated for completion by 2035, this route runs roughly 20-50 kilometers from the LAC, traversing the disputed Aksai Chin region through the Galwan Valley to Pangong Tso Lake, where China is establishing a substantial and long-term military presence.

Satellite imagery reveals new PLA headquarters and garrisons, accompanied by trenches, revetments for equipment storage, and shelters for weapons.

Additionally, a new radome, likely for signal intelligence collection or radar purposes, is under construction on a mountain peak north of the lake; moreover, just 23 kilometers away, a bridge is being hastily constructed across the Pangong Tso, linking the north bank, claimed by India as part of Ladakh, to the south bank in Tibet.

This bridge could facilitate the movement of PLA troops and equipment and serve as a means for China to establish territorial claims on the ground.

India’s Infrastructure Response

The build-up is not unilateral, as India has accelerated its construction of dual-use infrastructure along the LAC since 2020.

In the eastern sector, the Arunachal Frontier Highway, a 2,000-kilometer road following the McMahon Line, is under construction; starting at Mago in Arunachal Pradesh near Bhutan, the highway passes through Tawang and ends at Vijayanagar near Myanmar.

It Is expected to be completed by 2027 and located 20 kilometers from the LAC; it will enhance the mobility of Indian Army troops and equipment across valleys characterized by rugged terrain and harsh climate.

In Arunachal Pradesh, several other projects are in progress, including the East-West Corridor highway, the Trans-Arunachal Highway running the entire length of the state, and numerous smaller roads, bridges, tunnels, air bases, and heliports.

The 12-kilometer-long Sela Tunnel, set to provide all-weather connectivity to Tawang near the LAC, is critical for the Indian Army as it conceals its regional movements from PLA observation at the Sela Pass, situated at an altitude of 4,000 meters above sea level.

In April, the Indian government initiated the $600 million “Vibrant Villages Program” to develop 2,967 villages along the LAC. This program, which bears some resemblance to the CCP’s “well-off villages” initiative, includes the construction of roads, public services such as water supply, electricity, and internet connectivity, as well as healthcare centers.

The first phase, spanning 2023-2026, focuses on building 662 villages; while the program has yet to exhibit signs of civilian-military integration akin to its Chinese counterpart, comments from Indian Army personnel suggest that this may change.

Rebalancing the Indian Army

India’s military response reflects New Delhi’s acknowledgement of the altered strategic dynamics along the Sino-Indian border.

Following the 2020 clashes, Shivshankar Menon, former Indian ambassador to China and national security advisor, observed that “political relations will now be more adversarial, antagonistic… there is no grand bargain.” The 2020 crisis and subsequent CCP activities have, for India, ruptured the entire bilateral relationship.

In addition to the establishment of new border management infrastructure, India’s recognition of a broader threat has prompted a reconfiguration of its military forces away from Pakistan toward the LAC.

In 2021, the Indian Army reoriented its I Corps, one of its three strike corps, into a mountain strike formation responsible for launching offensive strikes across the LAC from Ladakh; previously, the I Corps had been tasked with penetrating Pakistani territory during wartime.

India’s 17 Mountain Strike Corps (MSC), which had been the only strike corps dedicated to offensive operations against China along the LAC’s western and eastern sectors until 2021, has also received 10,000 additional troops and equipment.

It has been exclusively redirected to focus on the LAC’s eastern sector, while I Corps concentrates on Ladakh in the west. Since 2022, the 17 MSC has participated in the Army’s Integrated Battle Group trials, aiming to create more flexible and technologically advanced units within the Indian Army.

Numerous other units have similarly been instructed to concentrate along the LAC, particularly in the middle section in Uttarakhand. As of 2021, over 50,000 Indian troops are stationed along the LAC, with border stability being a prerequisite for any normalization of relations with China.

CCP’s Salami Strategies

In January, Indian officials reported an increased PLA troop presence along the LAC’s eastern sector near Arunachal Pradesh. While updated figures are not publicly available, as of July 2020, the PLA deployed over 200,000 soldiers to its Western Theater Command (WTC), responsible for overseeing the entire Sino-Indian border region, including Arunachal Pradesh.

The addition of troops to an already substantial military presence, combined with CCP concerns about American forces in the Indo-Pacific, suggests the CCP’s heightened prioritization of the WTC and the LAC.

The PLA’s strategy along the LAC mirrors its approach in the South China Sea, employing a combination of hybrid and salami-slicing tactics. Along the LAC, Chinese forces have patrolled up to their claimed LAC, while the Indian army generally stayed short of the LAC, only approaching a line of 65 patrolling points (PPs) a few kilometers from the understood border.

Taking advantage of this unpatrolled gap, the PLA appears to have shifted the LAC back to the PPs line within Indian territory; as of January, India had lost access to 26 of its 65 PPs; this de facto cession of territory under Indian control to China demonstrates the effectiveness of these tactics.

On April 1, China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs released an updated list of “standardized geographical names” for 11 places in Arunachal Pradesh, containing names in Chinese, Tibetan characters, and pinyin.

China labeled this a “legitimate move and China’s sovereign right,” emphasizing that Arunachal Pradesh, or “South Tibet” as per the CCP, has been its territory since ancient times. This is not the first time China has attempted to advance its territorial claims through renaming localities, as similar lists were issued in 2017 and 2021, just prior to the CCP’s Land Borders Law taking effect.

The Viewpoint

Diplomatic efforts between India and China, including recent meetings of joint working groups on border issues, have yielded limited results.

The same is unsurprising, as sustained diplomatic exchanges obscure the reality of rapidly militarizing developments along both sides of the LAC; as a matter of policy, New Delhi has placed the border dispute at the center of Sino-Indian relations and without a new modus vivendi, competition will persist.

The CCP is likely to continue developing military capabilities within operational proximity of the LAC and advancing its salami tactics, as it did following the 2020 clashes and in line with its policies for national rejuvenation.

Military and infrastructure developments along both sides of the LAC will likely lead to further investments; with more troops from both sides in relatively closer contact, the risk of destabilizing incidents increases and the most probable scenario is continued escalation, with an elevated potential for conflict.

Other points of contention between India and China, including potential naval standoffs in the South China Sea, developments in Tibet related to the Dalai Lama’s succession, economic sanctions, China’s strategic alignment with Pakistan, and cyberattacks such as those targeting India’s electrical grid, add additional pressure on both Beijing and New Delhi.

However, it is challenging to predict whether either side will opt for escalation or de-escalation.

A less likely scenario would involve the latter and a substantial disengagement from the LAC; for instance, renewed violence could push Beijing and New Delhi to finally delineate and demarcate the LAC.

Such a settlement would be a significant achievement, freeing their militaries to focus on other strategic priorities, yet the CCP’s emphasis on sovereignty and India’s growing assertiveness make this outcome unlikely.

The long-standing historical shadow is likely to persist, with ample potential for future conflict.