Inflation VS Income: The Slow Bleed Of The Middle Class

The Incredible Shrinking Paycheck Of Indian Middle Class Where Your Salary Never Catches Up to Your Bills

In a country where economic headlines trumpet double-digit GDP growth and technological progress, a curious phenomenon unfolds in the lives of common man. For example, the water tank of 6000 litres that once cost ₹500 in Bengaluru now demands ₹800 from your wallet. Your child’s school casually sends a notice about a 15% fee hike “to maintain educational standards.” The hospital bill makes you wonder if they accidentally charged you for someone else’s treatment, too. Meanwhile, your income increment letter sits on your desk, proudly announcing a “competitive” 8% raise.

Welcome to the peculiar mathematics of modern living, where your income and expenses seem to operate in parallel universes with distinctly different rules of arithmetic.

This isn’t just about inflation; it’s about the systematic erosion of purchasing power that leaves millions feeling perpetually out of breath in the race to maintain their standard of living.

The phenomenon isn’t new, nor is it unique to India. The same issue has perplexed the common man throughout history: “If the economy is booming, why am I struggling more than before?” Understanding how the cost of basic services rises faster than incomes, resulting in a growing disparity that leaves people increasingly impoverished in real terms, even while nominal incomes rise, is the key to the solution.

Let’s examine this paradox through the lens of everyday life in contemporary India, where this economic mystery unfolds with remarkable consistency across urban centres and small towns alike.

The mathematics of feeling poorer isn’t complicated. When the water tanker that previously cost ₹500 now requires ₹800, that represents a staggering 60% increase in a single year. This isn’t a luxury item one can simply choose to forego—it’s water, the most basic necessity of human existence. In cities like Bengaluru, Chennai, and Delhi, the privatization of this essential resource has transformed accessing clean water from a fundamental right into a commercial transaction with profit-maximizing entities.

Medical inflation in India consistently hovers around 14% annually, far outstripping general inflation rates. A simple hospital visit that cost ₹10,000 five years ago might easily run ₹20,000 today. The scenario becomes even more dire when considering serious medical conditions. Treatments that once consumed a month’s income now devour six months’ worth of earnings, pushing families into debt spirals that can last decades. The ancient Sanskrit saying “Arogya param labh” (health is the most incredible wealth) has taken on a cruelly literal meaning—good health has indeed become a luxury that only the wealthy can consistently afford.

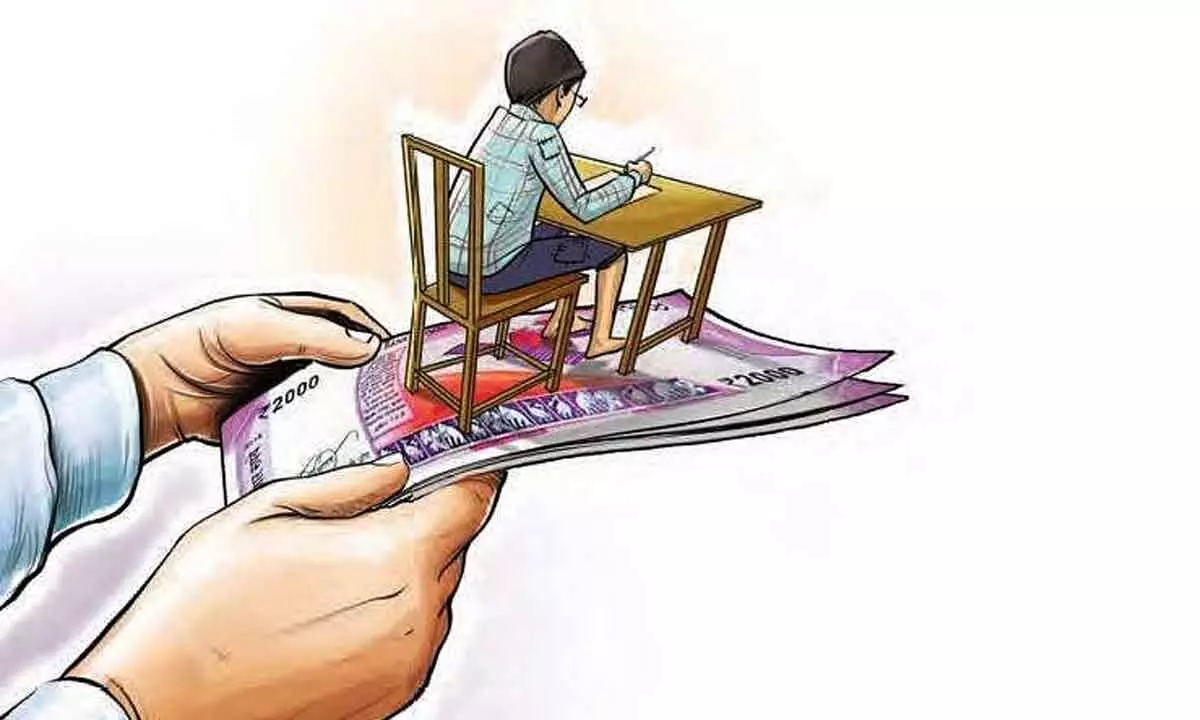

Education costs have metamorphosed into perhaps the most aggressive example of this phenomenon. Schools that once charged reasonable fees now position themselves as “premium institutions” with annual increases of 15-20%. The parents who grew up paying nominal fees for quality education now find themselves allocating significant portions of their income to provide the same for their children. The revered guru-shishya tradition, where knowledge was considered too sacred to be commercialized, feels like a quaint fairy tale in an era where education has become one of the most profitable business ventures.

Even your mobile phone bill, which is a modern necessity for participation in society, is projected to increase by approximately 20% this year. The digital bridge that was supposed to democratize access to information and opportunities is quietly becoming another tool for extracting more from the common man’s wallet.

The fascinating aspect of this economic reality is how it persists regardless of headline GDP growth figures. India’s economy has expanded impressively over decades, yet the common man feels an increasing slash on their pocket, which are similar to historical patterns observed across civilizations, where economic growth doesn’t automatically translate to improved living standards for the majority.

In 19th century Britain, during the height of the Industrial Revolution, factory owners and industrialists saw their wealth multiply exponentially while workers lived in squalid conditions with barely subsistence incomes. Charles Dickens wasn’t writing fiction so much as documenting the reality of a “booming economy” that left the majority behind. As he pointedly wrote in “Hard Times,” “It was a town of red brick, or of brick that would have been red if the smoke and ashes had allowed it.” The economic prosperity remained invisible to those whose labour created it.

Similar patterns emerged during America’s Gilded Age when robber barons accumulated unprecedented wealth while the average worker struggled. As Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner, who coined the term “Gilded Age,” observed, it was an era where a thin gold gilding covered severe social problems.

In post-independence India, this pattern has played out with remarkable consistency. During the License Raj era, economic growth was constrained, but the benefits were at least theoretically distributed through a managed economy. With liberalization, while GDP growth accelerated impressively, the gap between headline economic figures and lived experience widened for many citizens.

The underlying cause of this persistent gap between economic growth and personal prosperity isn’t merely market forces operating neutrally. At its heart lies what economists politely call “rent-seeking behaviour” but what most citizens recognize plainly as corruption. The water tanker you shouldn’t have to pay for in the first place, the school fees that seem disconnected from actual educational inputs, and the medical bills inflated beyond reason; all represent a systemic extraction of value without corresponding creation of value.

In a properly functioning system, the taxes paid by citizens would ensure basic services are provided affordably, if not freely. The Indian Constitution envisions the state as responsible for ensuring citizens’ welfare, yet the lived experience suggests a completely 180-degree different reality. The substantial tax revenue, both direct and indirect, paid by citizens often disappears into a rusting bureaucratic black hole, emerging as neither services nor infrastructure.

Mathematics becomes even more punishing when one considers how this affects different economic classes. For a family earning ₹25,000 monthly, a 60% increase in water costs represents a fundamental budget crisis. For someone earning ₹2,50,000 monthly, it’s an annoyance. This creates what economists call a “regressive effect,” where those with less income bear a proportionally higher burden, widening already substantial inequality.

Historical evidence suggests this pattern isn’t inevitable. The post-World War II economic boom in Western economies saw wage growth that actually outpaced inflation for decades, creating broad-based prosperity. South Korea’s economic miracle from the 1960s onward saw rising incomes across sectors, lifting millions into middle-class comfort. Singapore transformed from a resource-poor island to a global financial centre while ensuring citizens benefited tangibly from the growth.

The key difference in these success stories wasn’t merely GDP growth but how that growth was distributed and how corruption was managed. When essential services remain affordable and accessible, even modest income growth translates to improved living standards. When basic services become extraction opportunities, no nominal income growth seems adequate.

In contemporary India, this disconnect plays out daily in millions of households. A Software engineer in Bengaluru earning what would be considered an impressive income globally still find themselves calculating whether they can afford both quality education for their children and retirement savings. A government employee in Lucknow with employment security still worries about a potential medical emergency wiping out decades of careful saving. A factory worker in Surat sees their supposedly sufficient income eroded by rising housing costs that claim an ever-larger percentage of their income.

The economist Thomas Piketty captured this phenomenon succinctly in his work on inequality: capital tends to accumulate faster than economies grow, and certainly faster than income increase. This creates a natural divergence where those who own assets prosper disproportionately compared to those who rely primarily on labour income, making a K-shaped economy; and without corrective mechanisms, this divergence amplifies over time.

In India’s case, this economic principle operates alongside a system where essential services become profit centres rather than public goods. Water, which falls from the sky and should be managed as a community resource, becomes a commercial product with a markup that would make luxury goods manufacturers envious. Education, traditionally viewed in Indian culture as the greatest gift one generation provides to the next, transforms into a business opportunity with captive customers. Healthcare, which in many comparable economies is considered a basic right, becomes a financial nightmare for families already struggling with other rising costs.

The situation brings to mind the age-old Hindi proverb, “Jaise loha lohe ko kaat-ta hai, waise aadmi aadmi ko kaat-ta hai” (As iron cuts iron, so man exploits man). The exploitation isn’t always dramatic or visible—it’s the slow, steady extraction through a thousand small increases that collectively drain household finances.

This reality is particularly frustrating because it persists regardless of the political party in power. Governments change, and economic policies shift, but the fundamental experience of watching essential services grow increasingly unaffordable continues without any doubt, suggesting that the issue isn’t merely about specific policies; rather they are deeper structural problems in how the economy functions and how public resources are allocated.

The historical context provides further insight. During British colonial rule, wealth extraction from India was explicit and unapologetic. Post-independence, while the extractors changed, many citizens would argue the extraction continued through corruption, inefficiency, and misalignment of incentives. The colonial tax collector was replaced by the license raj bureaucrat, who was later replaced by the privatized service provider charging monopolistic rates.

This pattern isn’t unique to India. Latin American economies have struggled with similar dynamics for generations, creating what economists call the “middle-income trap”—where nations achieve moderate prosperity but struggle to translate that into broadly shared well-being. The phrase “so far from God, so close to the United States,” attributed to Mexican President Porfirio Díaz, might be adapted for the average Indian citizen as “so far from economic headlines, so close to financial anxiety.”

What makes the Indian experience distinct is the contrast between the country’s remarkable technological and economic achievements, named as ‘Vishwa Guru’ image and the persistent struggle of AAM AADMI to secure basic necessities at reasonable costs. The nation that can launch satellites economically, provide IT services globally, and produce world-class pharmaceuticals somehow struggles to ensure its citizens can access water without financial strain.

The consequences extend beyond household budgets. When citizens must allocate increasing resources to secure basics, their ability to invest in education, entrepreneurship, and other activities that drive long-term growth diminishes. The child whose parents cannot afford additional educational resources may never develop skills that would have contributed significantly to the economy. The potential entrepreneur who spends their savings on medical bills rather than a business idea represents innovation that never materializes.

This creates a negative feedback loop where addressing immediate needs constrains future potential, which in turn makes addressing future needs even more challenging. Economists call this a “poverty trap,” but it’s increasingly affecting middle-income households as well, creating what might be termed a “middle-class trap.”

The solution isn’t mysterious, though it is challenging to implement. It requires reimagining essential services as public goods rather than profit centres of specific business families of the nation, addressing corruption systematically rather than symbolically, and ensuring economic growth translates to improved living standards rather than just impressive statistics.

For the common man wondering why their supposedly adequate income never seems to stretch far enough, understanding these structural factors provides some context. The experience isn’t a personal failure of financial management but a systemic outcome of how essential services are conceptualized and provided.

As the ancient Sanskrit verse advises, “Vidya dadati vinayam” (Knowledge gives humility). Perhaps the first step toward addressing this persistent gap between economic growth and personal prosperity is acknowledging its systematic nature rather than accepting it as inevitable.

In the meantime, citizens will continue their creative mathematics—calculating how to make incomes that grow at 8% cover expenses that increase at 15-20%. They’ll continue wondering why the water that falls freely from the sky somehow costs ₹800 per tanker. And they’ll continue hoping that someday, the economic headlines about India’s growth will translate to something tangible in their daily lives beyond higher bills with stagnant services.

As the wise old saying goes, “Aata daal ka bhav pata hota hai” (The value of flour and lentils is what really matters). No matter how impressive the economic statistics, if the basics of life grow increasingly unaffordable, the growth remains theoretical rather than lived. Until that fundamental equation changes, your income will indeed continue to grow slower than the growth rate of necessary services, making each passing year a more challenging mathematical puzzle for household budgets across India.