Showing ‘The Bengal Files’ To Kids: The Art Of Killing Innocence For Propaganda!

When Filmmaking Becomes Child Endangerment Disguised As Art!

On September 12, filmmaker Vivek Agnihotri proudly shared a photograph of families, including young children, attending a screening of his latest film ‘The Bengal Files’, which is an “A”-certified (adults-only) film due to its graphic violence. YouTuber Dhruv Rathee immediately called out Agnihotri by saying “Are you seriously making children watch an adult-rated film? This should be a crime. You are traumatising their childhood by showing them so much blood, gore and violence.” Rathee’s rebuke, which quickly went viral, has ignited a broader debate revolving around,

“Why allowing kids to watch such violent content like ‘The Bengal Files’ is harmful, and how did it happen despite rules meant to prevent it?”

This article critically examines the controversy and delves into urgent questions it raises. We explore psychological research on violent media’s impact on children, India’s film rating enforcement (and lapses), parental awareness and content warnings, the role of the Censor Board (CBFC) in protecting minors, and whether The Bengal Files approaches its harrowing historical subject matter in a responsible or harmful way for young viewers. We also consider how graphic depictions of communal violence might skew a child’s understanding of history, what alternatives exist for teaching history age-appropriately, the societal costs of normalizing extreme violence for kids, and how India balances filmmakers’ freedom of expression with the duty to shield children from harm.

Does Violent Content Traumatize Kids? (Evidence of Long-Term Harm)

Psychologists and pediatric experts overwhelmingly caution that exposing children to extreme violence, gore, or trauma on screen can inflict lasting emotional and behavioral damage. Decades of research globally and in India support these concerns:

- Fear, Anxiety and Nightmares: Young children have vivid imaginations and struggle to distinguish fiction from reality. Violent or gory images can activate the brain’s fear circuitry, triggering stress hormones as if the child were in real danger. Counseling psychologist Srishti Vatsa explains that horror/gore films provoke intense reactions, even if our “brain” knows a movie isn’t real, the body reacts with increased heart rate, tension, cortisol and adrenaline. In children (with still-developing brains), this can create immediate distress as many kids feel restlessness, jumpiness or anxiety after witnessing violent scenes. Nightmares are a common repercussion. The American Academy of Pediatrics notes that “media violence can contribute to nightmares and fear of being harmed” in children. In short, graphic violence can quite literally haunt a child’s dreams and instill a lasting sense of insecurity.

- Lasting Trauma & Phobias: Beyond short-term fright, repeated exposure may lead to long-term anxieties or phobias. Mental health experts observe that children who see graphic violence can develop new fears (e.g. fear of the dark, fear of being alone) that persist well after the movie ends. Vatsa gives a striking example where an entire generation who saw certain violent films now cannot drive behind a log truck without panic, which is a phobia traced to traumatic scenes in Final Destination. For a child, witnessing massacre or gore (like in The Bengal Files) could similarly leave psychological scars associated with places, communities or situations depicted. One viewer recalled watching a brutal film (Sethu) as a child and taking “years to emotionally dissociate from that harrowing experience.” Such anecdotal evidence, echoed by many, underscores how childhood exposure to violence can leave indelible trauma.

- Desensitization and Aggression: Paradoxically, another outcome is the numbing of empathy. If children are repeatedly shown bloodshed, they may start seeing it as “normal.” This was the same concept when the movie ‘Animal’ was released. Research indicates that violent media exposure significantly correlates with desensitization to violence. Over time, kids may become less shocked by real-life violence, less sensitive to others’ pain, or even more aggressive themselves. One Indian psychologist notes that “exposure to violent audiovisuals can desensitize children to violence and make them more prone to aggressive behavior.” This is backed by extensive studies where children who watch a lot of violence often show increased hostile or imitative behavior and a tendency to use violence as a “problem-solving tool”. Aggressive play can spike even after a single violent movie. For instance, an experimental study found that children (aged 8–12) who watched a film with gun violence were far more likely to grab and “fire” a toy gun at others shortly after. The American Academy of Pediatrics warns that media violence contributes to aggressive behavior in some children and “desensitization to violence”. In plain terms, regular violent content can blunt a child’s natural aversion to cruelty, making brutality seem acceptable or even exciting.

- Emotional and Cognitive Impact: Young viewers aren’t just at risk of aggression. They can suffer wider emotional disturbances. One recent review emphasizes a link between media violence and anxiety/depressive symptoms in adolescents. Frequent exposure can distort a child’s perception of reality, leading to “a sense of a hostile, crime-prone world” that fuels chronic anxiety. Some kids may withdraw, lose sleep (insomnia), or exhibit regressive behaviors (bed-wetting, clinging to parents) after consuming traumatic content. In serious cases, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)-like symptoms can emerge if the child has personally experienced violence in the past; graphic scenes may re-trigger flashbacks or emotional shutdown similar to real trauma. Pediatric therapists note that children with existing anxiety or trauma histories are especially vulnerable as their stress response might “misinterpret on-screen dangers as real threats,” compounding their trauma.

In summary, child psychology evidence is unequivocal. Exposing kids to extreme violence and gore (like that depicted in The Bengal Files) puts them at risk of nightmares, anxiety, phobias, desensitization, aggression, and long-term emotional dysregulation. For developing minds, such content is far from harmless as it can fundamentally alter how a child sleeps, feels and behaves. As Dhruv Rathee admonished, it can “traumatise their childhood”. This raises the question that how did children gain access to an adults-only film in the first place? Are India’s safeguards failing?

Are Film Ratings in India Clear and Enforced, ENOUGH?

India does have a film rating system intended to protect minors from inappropriate content. The Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) classifies films into categories:

- U (Universal)

- U/A (parental guidance for under-12)

- A (Adults only, 18+)

- S (restricted to a special class)

The Bengal Files was duly rated “A” for its depictions of grisly violence, meaning no one under 18 is permitted by law. On paper, this is a clear safeguard. In practice, however, enforcement often falls short, as this incident highlights. Well, regulations on paper and broken rules in reality is not a new thing; it’s a common phenomena…

Indian cinemas are expected (and legally required) to bar entry to underage viewers for A-rated films, but implementation is patchy. According to a former CBFC CEO, the Board has even issued official notices reminding all cinemas to uphold age restrictions after receiving “a lot of complaints” about children being taken to adult films.

Theaters are supposed to check IDs and display warnings. For instance, many multiplexes put up prominent signs or announcements that “This film is A-rated and viewers must show age proof.” Indeed, prior to The Bengal Files, when a violent film (Coolie) got an A certificate, some cinemas proactively printed posters stating “Valid age proof is required”. Ticket-booking apps and box offices also usually mark A-rated shows with an age disclaimer. In theory, these safeguards should prevent any child from entering an adult screening.

Why, then, were children present at The Bengal Files? The answer exposes a cultural and enforcement gap. Despite clear ratings, many Indian parents routinely bring kids to adult movies, and theater staff often struggle to stop them. “In India, movie time is family time, and parents rarely leave their children behind, even if the rating is clearly displayed,” notes one cinema exhibitor. Especially in smaller cities and towns, ushers either don’t bother or don’t dare to enforce the rules.

An exhibitor from a Tier-II city admits that “In Tier-II and Tier-III cities, no one asks and no one stops kids from entering. And honestly, parents turn into street fighters if you tell them not to bring kids.” Another theater manager recalled a parent retorting angrily, “Now cinema wale (the theater guys) will tell us what’s good or bad for our child?”. Such attitudes where parents insisting they know best or that “it doesn’t matter, the child won’t understand or will sleep through it”, lead to frequent flouting of age rules.

Even in big city multiplexes with stricter staff, determined parents often find ways. They may buy tickets online (bypassing the human ticket checker) or simply argue and guilt-trip the ushers. “If stopped, their excuses are gold that ‘mera bachcha so jayega (my child will sleep)’ or ‘toh ab bache ko kahan le jaayein? (then where do we leave the kid?)’,” recounts one cinema employee.

On busy weekends, staff may be too overwhelmed to verify every young face in a packed hall. As a result, children slip into adult films surprisingly often. A recent media investigation bluntly titled it “Mission Impossible: Stopping Indian parents from bringing kids to A-rated films”. Despite rules, this “ongoing issue undermines the purpose of film certifications”, rendering ratings futile if kids get in anyway.

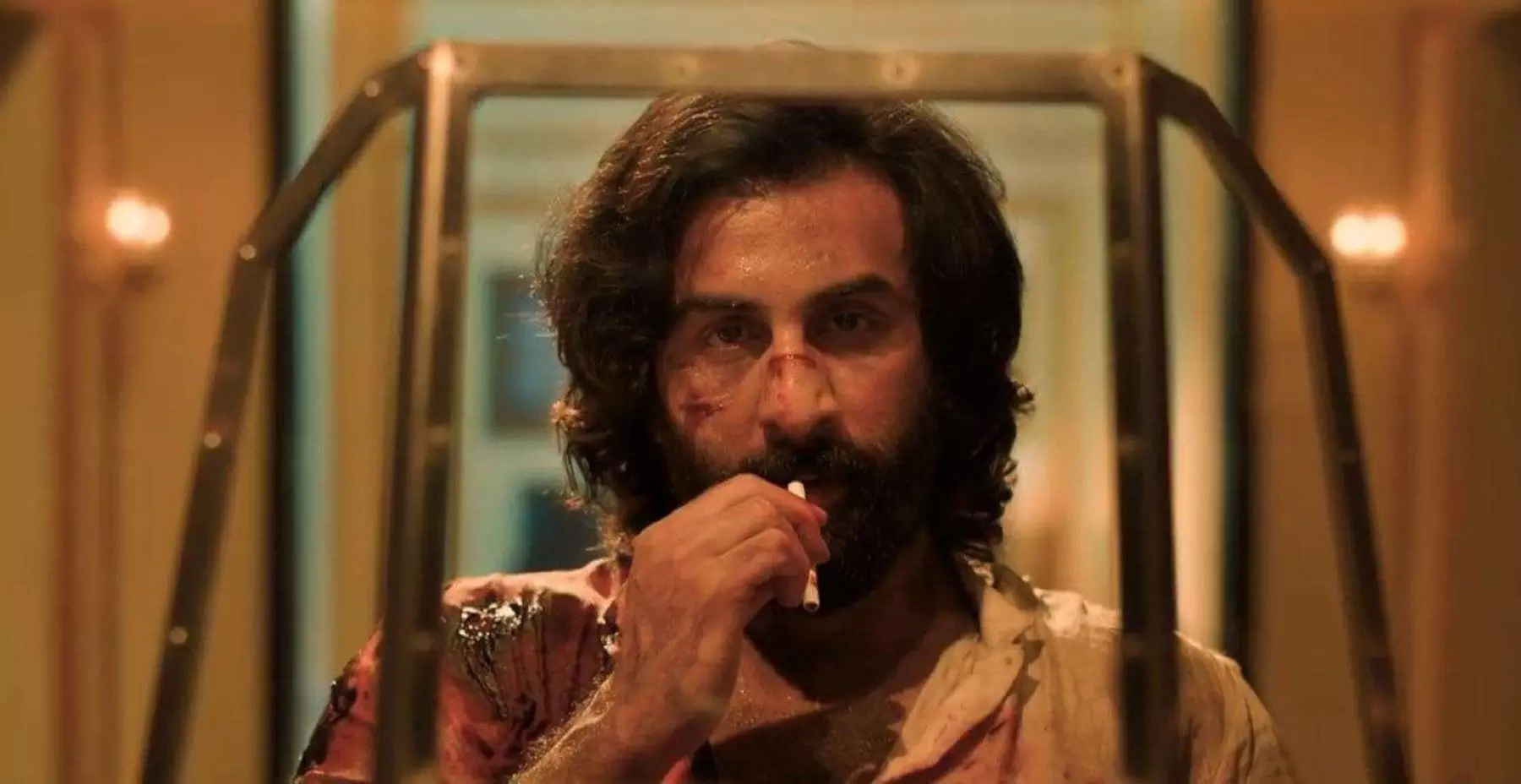

In the case of The Bengal Files, Vivek Agnihotri’s own actions might have compounded the problem. He openly shared a photo of children in the audience as a point of pride. This suggests the screening could have been a special show or premiere where enforcement was lax, possibly even with the filmmaker’s acquiescence. (Online sleuths noted the image looked artificial, sparking rumors it was AI-generated. But either way, the implication was clear that kids were present at an A-rated film’s screening.)

Legally, allowing minors into an adult film is indeed a punishable offense in India. Under Section 7 of the Cinematograph Act, 1952, any theater owner or distributor who permits a child to watch a film “not certified for their age” can face up to 3 years imprisonment and/or a ₹100,000 fine. This law underscores that the onus is on cinemas to enforce ratings.

However, enforcement tends to be inconsistent. Industry insiders acknowledge that after occasional crackdowns or reminders, things improve “for some time, at least”, but old habits soon return. One film executive lamented, “There is so much fight over certifications. But it’s all pointless when kids are allowed anyway.” In essence, the best ratings system means little without compliance on the ground.

So, while the rating (“A”) for The Bengal Files was perfectly clear, the safeguards failed due to a mix of parental negligence and spotty enforcement. Educated, urban parents are not immuneas many simply feel their child can handle it, or they prioritize convenience (taking the kid along rather than hiring a babysitter). As one observer put it, “we’ve seen so much that nothing shocks us anymore”, which is a disturbing normalization that may blind some parents to what is age-appropriate.

The Bengal Files incident thus shines light on a broader phenomenon in India where film ratings exist, but they are often ignored, sometimes by audiences (sneaking in kids) and sometimes by exhibitors (turning a blind eye to sell tickets). The result is that children are accessing content meant only for adults, with potentially serious consequences.

Do Parents Know What They’re Signing Up For? (Content Warnings & Parental Awareness)

One pressing question is whether parents or guardians were fully aware of The Bengal Files’ content, its extreme violence and disturbing themes, before bringing their children. Were there adequate warnings in trailers, posters, or media coverage to alert them? Or did some parents walk in uninformed?

In the age of information, it’s unlikely that parents were completely oblivious. The Bengal Files was widely discussed in news and social media, often with emphasis on its gory nature and “A” rating. Reviews explicitly called it “disturbingly graphic, gory and gruesome”. The film’s trailer (if similar to The Kashmir Files’ marketing) presumably hinted at intense violence and historical carnage. Moreover, theaters usually mark tickets or display signage showing the “Adults Only” certification at the point of purchase. According to cinema operators, “People are already informed during ticket booking when it’s an A-rated film. We give content warning,” koi maanta nahi hai (no one listens).” This suggests that at least some warnings were provided, but possibly not heeded.

However, it’s worth examining how content warnings were delivered and if they were sufficient. A small “A” symbol on a poster or a line of text on a booking app can be easy to overlook or ignore. Unless a parent actively seeks out details (like reading reviews or checking Common Sense Media–style parental guides), they might not grasp how extreme the violence is. In promotional materials for The Bengal Files, the focus was likely on its historical angle, e.g., “the untold truth of 1946’s Direct Action Day.”

Some parents could interpret this as an educational historical drama, not realizing it graphically shows massacres and rapes. If the marketing leaned on patriotism or truth-telling, families might have assumed “important history, perhaps intense, but something kids can learn about.” For instance, the film’s tagline about “chapters of history deliberately suppressed” might frame it as a must-know story, potentially downplaying the trauma of its depiction.

That said, there is evidence that many people did know the film’s nature. Vivek Agnihotri himself hyped The Bengal Files as the third in his trilogy of hard-hitting “Files” films known for unflinching violence. His earlier film The Kashmir Files (2022) gained notoriety for brutally realistic scenes of killings. It’s probable that any parent familiar with that film (which The Bengal Files has been compared to) would expect similar or worse violence this time.

Indeed, The Bengal Files not only earned an A certificate but reportedly had 29 voluntary cuts by the makers to get approved, indicating the content was extreme even by adult standards. If parents were unaware of this, one might ask why Did they not research the movie at all? Or did the “historical truth” narrative overshadow the content warnings in their minds?

It’s also possible some parents knew it was violent but assumed “my child can handle it”. As noted, a common excuse is “bachche ko samajh nahi aayega”, the child won’t understand anyway. This reflects a belief that graphic images won’t affect a kid if they can’t grasp the context. Unfortunately, psychology tells us the opposite that even if a child cannot follow the political storyline, the visual horror of blood and gore speaks a primal language of fear.

A toddler may not know who is killing whom, but they see frightening imagery that can imprint on their subconscious. So if any parent thought, “It’s just history, and my 8-year-old doesn’t know about Hindus vs Muslims, it’ll be fine,” they severely miscalculated the impact of seeing people brutally hacked or a body being beheaded on screen (scenes which The Bengal Files indeed contains).

Could theaters have done more in-the-moment? Perhaps verbal warnings at the door (“This film has graphic violence, please consider not taking young children”) might dissuade some last-minute. In countries like the US, it’s not customary, but given the Indian context of families showing up with kids, a proactive approach could help. However, the primary responsibility lies with parents/guardians to check content suitability. The fact that Rathee’s criticism resonated suggests that many adults agree those who took kids to this film exercised poor judgment. It wasn’t ignorance so much as negligence or willful disregard of the content warnings.

One indicator of awareness is how audiences reacted after viewing. Were parents shocked and regretful upon seeing the gore with their child? Or were they unfazed? While we lack specific reports, the outrage online (led by people like Rathee) suggests that society at large found it appalling, indicating this is not normal practice. If some parents truly didn’t know, one would expect to hear contrite comments like “We had no idea it was so violent; we would never have taken our kids had we known.” So far, we haven’t seen such testimonials in the press, implying that those who brought children likely either knew the risk or didn’t consider it at all beforehand.

In summary, content warnings were present (the A-rating, media reviews describing gore), but their effectiveness hinged on parental diligence. This case exposes a need for better communication of extreme content ,perhaps stronger public advisories for films with graphic violence (similar to how some streaming shows display “Viewer Discretion: Contains graphic violence”). Theaters could also train staff to verbally caution parents attempting to take a minor in (some already do, but it could be more consistent). Yet ultimately, if a parent is determined or apathetic, warnings won’t stop them. This dovetails into the next question that what more could authorities do,or have done, to enforce the adult-only restriction?

Role of the Censor Board: Are Rules and Penalties Enough?

India’s Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) is tasked not only with rating films but also with guiding their appropriate exhibition. The CBFC issues certificates with clear age restrictions, and as discussed, showing an “A” film to minors is legally forbidden. On paper, the CBFC’s job is done once a film is rated, enforcement is up to cinemas (and local authorities). However, given the recurring breaches, one might ask, could the CBFC or other regulators do more?

Firstly, the CBFC guidelines themselves emphasize child protection. The rules state that any film “unsuitable for exhibition to non-adults” shall be restricted to adult audiences. They even caution that for a U/A film, parents should be notified if any material might disturb children under 12. For an A film like The Bengal Files, the expectation is absolute as no child should be admitted. The CBFC regularly communicates these expectations. As mentioned, it sent notices to cinemas reminding them not to allow kids into adult movies. With each A-certified film, the certificate comes with a stipulation that the producer and theater must ensure compliance.

Are there penalties when violations occur? Yes, as noted, the law prescribes hefty penalties (jail/fine) for theaters breaking the rule. But enforcement typically requires either random checks or complaints. It’s rare for police or inspectors to patrol theaters for underage viewers.

In reality, enforcement might kick in only if there is a high-profile complaint or incident (for example, if a child suffered a medical emergency due to a scary scene, prompting investigation). The CBFC itself doesn’t have a police force; it relies on local administration to uphold the law. Given the covert nature of slipping a kid into a movie, violations largely go unpunished and cinemas cover it up, and patrons won’t complain (since it’s the patrons themselves violating the rule!).

Some have suggested the need for stricter checks, like requiring ID for all viewers at adult films, similar to how bars check age. Large multiplex chains in metro cities occasionally enforce this (especially if a patron obviously looks underage). For instance, a Reddit user noted “PVR multiplex is very strict and will definitely not allow people below 18” for A movies. But this level of strictness is not uniform across India. The CBFC lacks resources to monitor each screening nationwide.

Another lever is holding filmmakers accountable if they encourage underage viewing. In this case, Vivek Agnihotri posting that photo arguably condoned the violation. While free speech allows Vivek Agnihotri to celebrate his film’s audience, one could argue an ethical responsibility that he might have instead discouraged families from bringing kids, stating “This film is not for children.” On the contrary, his “one picture says it all” post (with kids visible) sent a mixed message. The CBFC or Ministry of Information & Broadcasting could censure such behavior, but there’s no clear rule against a filmmaker welcoming kids to an adult film. The onus legally is on theaters and parents, not the director.

Censorship boards in some countries take additional steps. For example, the UK’s BBFC provides detailed content breakdowns for films so parents know exactly what to expect. The CBFC could consider issuing public content advisories in extreme cases (e.g., “The Bengal Files contains graphic images of violence including beheading and torture”), to be displayed prominently at cinemas. Although this might overlap with what the rating implies, a specific warning might have more impact on a parent wavering on bringing a child.

The question also asks “Are there penalties for cinemas or filmmakers if children are allowed access?” Filmmakers per se aren’t penalized unless they actively abet the violation. One could conceive that if a filmmaker organized a special screening and knowingly let minors in, it’s a grey area legally, but they could be criticized or even face public interest litigation for endangering children. In this case, beyond Rathee’s public shaming, there’s been no legal action.

It’s worth noting, ironically, that The Bengal Files faced legal challenges of a different kind where a petition in Calcutta High Court questioning its certification for allegedly distorting history and defaming a real person. That petition was dismissed, but it shows how certification decisions can be contested in court. In theory, one could file a PIL asking “Why did CBFC certify this film as A and not something stricter, or ensure safeguards?” But the CBFC’s mandate is certification, not enforcement in halls.

In summary, the CBFC has done its part by labeling the film 18+ and reminding theaters of their duty. The framework (ratings, legal penalties) exists, but enforcement is the weak link. The situation reveals a need for better implementation, maybe surprise checks, stricter penalties for repeat-offender cinemas, or even suspension of licenses if rules are flaunted. Some have even called for punishing parents who bring underage kids to violent films, which is a drastic measure that might be hard to enforce, but indicative of how seriously some view the issue.

Ultimately, rules are only as good as the societal commitment to follow them. The Bengal Files controversy indicates that both parental culture and exhibitor practices in India need reform to truly keep kids out of adult content. The next questions turn to the film’s content itself and its potential impact on a child’s understanding, assuming, as has happened, that children have indeed been exposed to it.

History or Horror: Is The Bengal Files Presented Educationally or Sensationally (Especially for Young Viewers)?

Vivek Agnihotri’s The Bengal Files is based on real, harrowing events of the Great Calcutta Killings of August 1946 (Direct Action Day) and the Noakhali riots that followed. These were episodes of horrific communal violence in pre-Partition India, where thousands were killed. Handling such sensitive historical material on film poses a challenge where “do you depict the brutality to convey its reality (educational), or does that easily become sensational and traumatizing?” Agnihotri has positioned his “Files” films as uncovering hidden truths of history. But many critics feel The Bengal Files is more exploitative than educational, especially given its graphic approach.

According to reviews, the film shows extreme scenes where streets strewn with dead bodies, civilians being massacred and raped “left, right, and centre”, a character literally cut into half and another beheaded on-screen. The imagery is “in your face” rather than implied. While this certainly drives home the horror of the events, one must ask that what context or nuance accompanies these depictions? Is the violence framed with historical explanation and a message of peace, or is it used to shock and provoke anger?

Critics say the film lacks nuance and subtlety. It “asks many questions about communal violence,” but the only answer it seems to land on is more violence. This suggests a possibly one-sided or inflammatory narrative, not ideally how one would “teach” history to the young. A nuanced educational approach would involve explaining causes, acknowledging multiple perspectives, and emphasizing lessons to prevent such hatred in future. From accounts, The Bengal Files instead heavily portrays one community’s atrocities (Muslim league supporters chanting slogans and committing killings) and the justified retaliation by the other (a Hindu figure Gopal Patha urging “10 Muslims for 1 Hindu” revenge). The sheer graphic nature tilts it towards sensational cinema rather than a documentary style.

For younger viewers, this is especially problematic. An adult might discern the filmmaker’s bias or dramatic license, but a child could take what’s shown at face value. If a child (say 10-12 years old) watches The Bengal Files, what do they absorb? Possibly, “In history, group X savagely killed group Y; group Y had to fight back savagely. The world is cruel and divided by religions.” Without proper context, this can be a terrifying and simplistic takeaway.

There’s little evidence that the film provides counter-narratives or balanced context that a young mind would need. For instance, are there any scenes showing humanity or cooperation amidst the carnage? Any post-script or disclaimer explaining that the film is a dramatized version or urging communal harmony now? Not that we know of. (Agnihotri dedicated the film to “all victims of communal violence”, which is a respectful gesture, but it doesn’t necessarily mitigate the traumatic content.)

Educational presentation would also involve guiding the audience through the historical significance. The Bengal Files, however, seems to conflate 1940s events with a present-day political narrative (the film intercuts to modern West Bengal with insinuations about “vote bank politics” and certain communities’ rising population). This blending of history with current politics can be confusing, even misleading, for a child, who isn’t equipped to understand the nuances. It might come across as “violence of the past is directly linked to people today”, potentially fostering communal bias (more on that in the next section).

In terms of being respectful to the historical trauma, opinions diverge. Supporters might argue showing the full brutality honors the suffering of victims (not sugar-coating what happened). Indeed, history was horrific; perhaps sanitized depictions wouldn’t convey the magnitude. However, the counterpoint is that excessively graphic dramatization can border on voyeurism or propaganda, rather than respectful commemoration. The Calcutta High Court petition by Gopal Mukherjee’s grandson claimed the film “distorts history” and defamed his grandfather. Though dismissed, it indicates concerns from those with a stake in historical accuracy.

For children, “educational” requires age-appropriateness. A college student might learn a lot from a brutally honest film about communal riots (though even adults debated The Kashmir Files’ intent, some calling it propaganda). But a child needs a gentler introduction to such dark chapters, ideally through discussion or moderated content. The Bengal Files provides no moderation as it plunges one into the horror. There are no “pauses” to contextualize or expert narrations to explain why things escalated. It is an immersive emotional experience. That is effective cinema for adults, perhaps, but it’s overwhelming and potentially traumatizing for kids (as we discussed earlier).

In summary, while The Bengal Files purports to shed light on a forgotten genocide (which could be a noble educational goal), the way it presents the material is highly graphic and dramatized, arguably tipping into sensational territory. No special measures appear to have been taken to make it palatable or instructive for youngsters, quite the opposite, it’s meant only for mature audiences capable of processing such content. If children do see it, they are likely to be shaken, not enlightened. They would need a lot of guidance to turn that disturbing viewing into constructive understanding, guidance which a dark theater showing a violent film simply does not provide.

This leads to a crucial concern. What happens to a child’s view of history (and of communities) if they see graphic violence without proper context?

Consider what The Bengal Files depicts; members of one religious community committing barbaric acts against another, and retaliatory barbarism in return. If a child from community A sees this, they might develop an intense fear or anger toward community B (especially if they don’t realize this was 75 years ago in a specific context). Communal tensions in India are still a reality; an immature mind could easily generalize “People of X community are violent”. The film reportedly has scenes with slogans like “Allah hu Akbar” accompanying violence, a child could misinterpret that as “those words = danger”. This is how bias can take root.

One could argue that any depiction of a one-sided massacre can skew views, for example, Schindler’s List shows Nazis committing atrocities; a child might think “Germans are evil.” However, films often include context or subsequent education (in schools) to explain the broader picture (e.g., not all Germans were Nazis, etc.). In the case of The Bengal Files, the concern is it may lack a balanced portrayal.

If it heavily emphasizes Hindu victims and Muslim perpetrators (which reviews suggest it does), it might reinforce a single-sided communal narrative. A more balanced historical approach might show both communities suffering and extremists on both sides, but the film appears to lionize one side’s reprisals as necessary. This could validate a notion of “hatred is justified when we’re wronged” to a young viewer, a dangerous lesson.

Moreover, graphic depictions embed themselves in memory strongly. A child who witnesses a beheading scene connected to a certain group could have a visceral reaction of either fear or vengefulness when that group is mentioned later. Psychologists warn that observing violence can distort a young person’s reality perception, making the world seem more hostile. In communal terms, it can solidify an “us vs them” mindset. Communal biases are often passed down through charged stories; here, a film serves that role powerfully.

Did the filmmakers include any disclaimers to contextualize events fairly? Possibly at the start there might be the standard note that it’s based on true events and some characters are fictional. But there is no indication of a foreword or afterword explaining context (e.g., detailing actual historical records, acknowledging that while events were real, the film dramatizes them). On the contrary, Agnihotri’s narrative stance (judging by The Kashmir Files too) is that mainstream narratives ignored these truths, and he is correcting the record. Such a stance can come off as one-dimensional. For children especially, black-and-white storytelling can harden into bias, they don’t yet appreciate the grey areas of history.

Additionally, viewing such violence can evoke hatred or desire for revenge even in someone who never previously felt it. If a Hindu child watches fellow Hindus being slaughtered in 1946 (with no broader lesson attached), they might, out of shock and empathy with victims, develop resentment toward Muslims as a category. Similarly, a Muslim child watching might feel either defensive or traumatized, thinking “people hate us and want to kill us”. In both cases, it breeds fear and mistrust between communities, precisely the opposite of what one would hope to teach the next generation about past communal violence.

A truly educational portrayal would strive to promote understanding and tolerance, showing the tragedy and futility of communal hatred, and perhaps highlighting figures who helped or instances of humanity amidst carnage. It’s unclear if The Bengal Files does any of that. The NDTV review suggests the film basically wallows in gruesome details and a narrative of ongoing victimhood and threat That, without counterweight, is not a healthy historical lesson for a child.

In conclusion, presenting historical violence graphically without nuanced context absolutely risks skewing a child’s understanding toward fear and bias. No evidence suggests The Bengal Files contains sufficient disclaimers or balanced storytelling to prevent that. On the contrary, its style may exacerbate communal biases if seen by impressionable audiences. This is a prime reason such content should remain restricted to adults, who at least have critical thinking abilities (even then, the film has been accused of polarizing viewers). For kids, it’s like handing them a live wire of hatred with no safety instructions.

If we continue down a path where events like children in The Bengal Files screenings are brushed off, we risk desensitizing our future society and perpetuating cycles of violence and fear. The societal norm should be that childhood is a time for age-appropriate learning, not premature exposure to every horror the world has to offer. As many have observed, Indian cinema is heavily a “family experience” culture, perhaps it’s time to redefine what appropriate family viewing is, instead of dragging the kids into content they’re not ready for.

From the freedom of expression side, Should a filmmaker self-censor for the sake of potential child viewers? Ideally, no, if the film is meant for adults, the filmmaker creates it for adults. It’s the responsibility of others to keep kids away. Agnihotri has the freedom to depict the 1946 violence in all its gruesomeness as part of his artistic vision and message. Many would say that’s his right, and that society’s job is to make sure the right audience sees it.

Where it gets complicated is when filmmakers blur that line for publicity or agenda; for instance, if one wants children or teens to see it to propagate a certain viewpoint (nationalistic, historical, etc.). Some critics suspect that with The Kashmir Files, there was a push to get even young people to watch, as it was treated like “required viewing” by certain groups. If a filmmaker is actively encouraging breaking age rules, then the balance is being undermined from the art side too.

So the balance in guidelines is, Adults can choose to watch disturbing content, that’s freedom; Children cannot, that’s protection. This is similar to how we handle many things (e.g., adults can drink alcohol, children cannot, etc.). It’s a compromise rather than banning the content altogether.

In conclusion, the intended balance in India is that filmmakers like Agnihotri are free to make challenging, even graphic content portraying history as they see fit, but it is meant exclusively for a mature audience. The guidelines exist to maintain that dividing line. When everyone respects it, we achieve a scenario where art flourishes without harming children. The Bengal Files incident shows the system isn’t foolproof, a wake-up call that all parties (censors, theaters, and parents) must be more vigilant.