4 years Of Ken-Betwa: Whose Thirst It Will Quench, Citizens Or Politicians?

Will Ken-Betwa Provide What It Promised Or Will It Be A Plague Of Political Favour?

Ken-Betwa After Four Years: Promise Or Politically Whimsical?

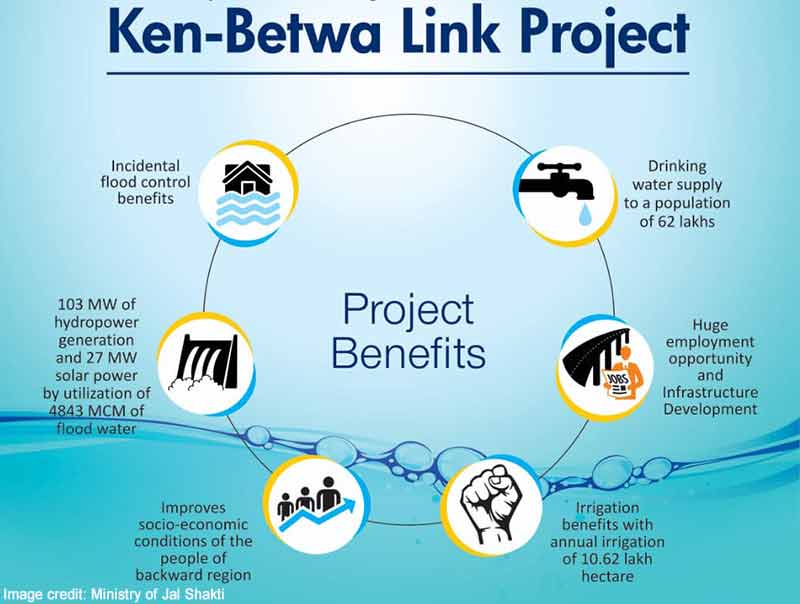

Four years on from the Cabinet’s nod, India’s first major river-link project, Ken-Betwa, still looks more like a political play than a solution to Bundelkhand’s woes. Officially launched by PM Modi in December 2024, the ₹44,605 crore scheme “transfers surplus water from the Ken to the Betwa” via the 77m-high Daudhan Dam and a 221-km canal. In Parliament, Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav recently said that the project will irrigate 10.62 lakh hectares, supply 194 MCM to 62 lakh people, and generate 103 MW hydropower (plus 27 MW solar).

The project is packaged as a lifeline for drought-prone Bundelkhand, a “project of national importance” that promises to “open new doors of prosperity and happiness” for 13 districts of MP and UP. These are the talking points. But, four years in, where’s the substance behind the slogans?

Promises vs. Problems: Official Claims

Promoters make Ken-Betwa sound golden. According to government sources, the Ken-Betwa Link Project (KBLP) will irrigate 10.62 lakh hectares (8.11 lakh in MP, 2.51 lakh in UP) and give drinking water to ~62 lakh people. It will generate 103 MW of hydropower plus 27 MW of solar energy, benefiting 10 districts in MP and 4 in UP. CM’s and ministers hype it as Bundelkhand’s salvation. The Union Govt. calls it the first “centrally driven” river-link under India’s National Perspective Plan, with all “environmental clearances… given” and “necessary steps” taken to protect flora and fauna.

Key touted benefits (per official statements) include:

– Massive irrigation: 10.62 lakh ha of farmland (8.11 lakh in MP, 2.51 lakh in UP).

– Drinking water for 62 lakh people (194 MCM annually).

– Power generation: 103 MW hydro + 27 MW solar.

– Phase I cost: ₹44,605 crore, to be built in 8 years.

– Political backing: Signed by the Jal Shakti Minister and the CMs of MP/UP (Mar 2021), inaugurated by PM Modi on Vajpayee’s birth anniversary Dec 25, 2024.

“Surplus water of Ken will be diverted to water-short Betwa areas,” the Jal Shakti Ministry insists. Officials depict a story of water shortage solved, crops saved, hydropower added and jobs created. Bundelkhand, a poor, underdeveloped region, is promised a lifeline and shower of projects. Hard not to swoon at the rhetoric: water, wealth, and well-being for the backward Bundelkhand – on paper, it sounds transformative.

Reality Check: Cost, Progress and Accountability

But promises alone don’t irrigate fields. Money has flowed, even too much, perhaps, too soon, while actual benefits remain illusory. Official records show that over the past three years, ₹3,969.79 crore has already been spent on Ken-Betwa out of a ₹4,469.41 crore budget. That’s nearly 90% of funds disbursed, yet construction has barely begun beyond felling a few trees and marking lands. In fact, as of mid-2025 about ₹3,969 crore has been expended. In other words, more than half of the Phase I budget is already gone, on land acquisition surveys, canal alignment, preparatory works and bureaucracy, but nothing tangible, like a single drop of diverted water, has reached the parched Bundelkhand fields yet.

Where is the money going? Official replies suggest it’s on land and rehab: 7,193 Project-Affected Families are identified and states are to handle their resettlement. Madhya Pradesh even approved a special “rehabilitation package” in Sept 2023. Fine. But with nearly ₹4,000 crore down the drain, progress should be visible. So far it isn’t. Work is not complete yet on the Daudhan Dam or the linking canal; the foundation stone was just laid, and authorities claim “implementation phase” recently began.

Strikingly, a recent briefing shows detailed project reports (DPRs) for 11 interlinking projects done and Ken-Betwa the only one “under implementation,” yet it has still expended funds at a rate that outpaces construction. The National Water Agency even claims Ken-Betwa is to finish by March 2030 – that’s another five years from now to complete what’s essentially still on paper.

Environmental and Social Toll

Meanwhile, Ken-Betwa’s price in trees and tribes has mounted. Officially, 17,101 trees are slated to be cut in MP alone, including 12,404 within Panna Tiger Reserve. The JWST (Jal Shakti) Ministry noted no protests have been recorded against these cuts, which is a suspiciously quiet consent. Nearly 7,193 families will be displaced (per the RFCTLARR Act). Activists point out that over half the project land is forest and reserves, meaning the “socio-economic prosperity” touted may come at the expense of nature and tribal rights.

If one hoped for compensation, one sees none clearly outlined. The official Rajya Sabha reply touts a special rehab package, but tribals themselves describe mere promises, unfulfilled. A report details that hundreds of tribal families have seen their ancestral lands claimed with scant dialogue or adequate compensation. Leaders of affected villages openly wept at the foundation ceremony, lamenting that “on that day, people from 8 tribal villages did not light their stoves” in mourning. They ask: if development is for our welfare, why are we first being sacrificed? As one Gond tribal put it: “we will lose our fields, trees, land… Without economic justice, we will never rebuild our lives.”

The environmental stakes are staggering. Earlier expert reports warned that Ken-Betwa could submerge nearly 9,000 hectares, including vital parts of Panna Tiger Reserve. For a landscape that had no tigers left until a recent reintroduction, the project threatens a rebound. Government conservation data note 79 tigers (2022) roam in a 2,840 km² forest complex around Panna.

According to tiger experts, the dam’s reservoir will inundate much of their range: “a substantial portion of Panna Tiger Reserve is under threat of submersion… at least 3-4 tigresses [will lose habitat], and around a million trees in the core area will be felled”. Additionally, rare vultures and a host of other wildlife face habitat loss. In response, the forest department’s own advisory committee had bluntly recommended in 2017 that Ken-Betwa “should not be given clearance”. Instead, the ministry plowed ahead after ‘special meetings’ during the COVID years and now gives verbal assurances about protecting biodiversity.

So, is any environmental quid pro quo offered? A government press note vaguely claims “all necessary steps are being taken to protect… biodiversity”, but no clear mitigation plan is publicized. There’s no detailed restoration scheme for the 17,000+ trees cut (out of 1.7 million reportedly marked). And we are a country already battling polluted air and receding forests. To cut thousands more trees for dubious gains is, critics sniff, reckless. As one environmentalist quipped, India can’t boast “green growth” if its forests drown more people’s homes.

Technical Doubts and the New Science

Beyond ecology, hydrologists and water managers have been uneasy. As early as 2016, then-Union Water Minister Uma Bharti had theatrically threatened to strike if the project wasn’t cleared, indicating political zeal over reason. Key experts have since said the Ken river basin is barely surplus. Former Water Resources Secretary Shashi Shekhar, for example, flatly asserted that the official claim of irrigating 10.62 lakh hectares is “coming out of the air,” contradicting ground reality.

He notes that actual rainfall and hydrology data for Ken vs Betwa do not justify moving water away from Bundelkhand at all – ironically, the upper Betwa (not even Bundelkhand proper) gets much of the benefit. South Asia water expert Himanshu Thakkar of SANDRP adds that the project’s own DPR shows its “primary objective is to provide water to the upper Betwa, which is not part of Bundelkhand,” effectively siphoning Bundelkhand’s meager water to other areas.

Independent hydrologists point out something odd: the Ken basin’s gauged surplus is tiny. In fact, districts in upper Ken have historically seen much less irrigation and storage; they appear “water-surplus” on paper only because no one tapped them yet. Tap them, and the illusion vanishes. Even the experts appointed in 2009–11 complained that the key data on flows were hidden from them as “state secrets,” so they couldn’t verify whether Ken truly had extra water to spare. Water bureaucrats insist this is all based on secret NIH studies, but refuse to share the modelling. It certainly raises the spectre of a politically cooked DPR.

Adding to the skepticism is emerging climate science. A 2023 study in Nature Communications warns that massive interlinking can alter monsoon patterns. Computer simulations show that the extra irrigation lakes and canals can increase evapotranspiration and change rain recycling, reducing rainfall by up to 12% in some arid regions during late monsoon. In plain terms: irrigating more in one basin can leave other areas drier than before. The Ken-Betwa link, transferring monsoon floods, might thus blunt downstream flows or paradoxically worsen drought conditions elsewhere.

Professor Subimal Ghosh (IIT Bombay) warns that altering terrestrial water cycles without rigorous study is “a recipe for trouble”. The project’s own hydrologists counter that Ken-Betwa mostly uses monsoon peaks, but critics note no updated downstream impact assessment appears to have been done. In fact, activists say the project sailed through without a fresh environmental impact study or modern cost-benefit analysis.

One startling statistic from an expert panel study: rainfall in districts crossed by Ken and Betwa in recent years (2020–23) has been virtually identical, yet Ken was labelled “surplus basin”. If that’s true, the scientific justification for robbing Bundelkhand’s upper reaches of Ken water is suspect. Climate models now suggest every river is connected through the atmosphere – what you do in one basin affects others. The practical upshot: even if a dam and canal are built, they might not solve Bundelkhand’s thirst and could even create new problems downstream.

Critics’ Verdict: “Politically Motivated Vanity Project”

It’s no surprise critics loudly question the entire endeavor. Environmentalists, hydrologists and former officials have all labelled Ken-Betwa a “politically motivated” gift to certain constituencies. Why now? The Union Cabinet cleared it in Dec 2021, months ahead of key state elections (Uttar Pradesh 2022; Madhya Pradesh 2023). Then PM’s December 2024 launch in MP bore all the hallmarks of an election-time pledge.

Leaders from the ruling party tout it as proof of development; opponents see vote-bank pandering. “It’s a political decision,” said one former MP wildlife chief. “Bundelkhand will suffer for decades to come.” (TheWire reported Chundawat’s blunt warning.) Conservatives and progressives alike suspect that this might be more about optics (water tanks and golden plaques) than actual water distribution.

Again, the numbers invite incredulity. The government’s target area and beneficiaries grew in media statements over the years – from 10 lakh ha to 10.62 lakh ha – even as on-ground feasibility dwindled. Critics note such figures “come out of thin air”. When asked if alternatives (like watershed management) were even explored, officials say “not to my knowledge.”

Independent voices like Shashi Shekhar claim the Supreme Court’s experts had recommended against it; they were overruled by political masters. The FAC and CEC had urged caution in 2017 (even calling a hydrology study); the government went ahead anyway. Some call this a classic case of confirmation bias: once the leadership decides on a flagship (Vajpayee’s “dream” project), all data is bent to fit.

From the environmental side, leading conservationists warn of long-term damage. As one ex-forest official lamented, the newly revived Panna tiger population (79 animals) would again be imperiled by an “artificial reservoir.” Without adequate corridors, shifting or confusing Tigers might lead to conflict or dispersal into farmland. Hundreds of villagers and tribals have already filed protests and petitions, claiming the link’s promised compensations are nowhere in sight (memorials to the President lament “8 Panna villages left empty”). And all this for a scheme that may not bring water where it’s needed most.

Political Stakes and Potential Beneficiaries

Who stands to gain if Ken-Betwa trundles on? Officially, 62 lakh urban and rural residents might someday sip from its flow. But skeptics see a different calculus. The ruling party (BJP) and its leaders in UP/MP have surely gained narrative value – “we’re solving Bundelkhand’s age-old crisis,” claims a triumphant caste-tinted poster. Senior party managers note that these districts have been historically neglected (even under Congress regimes).

A splashy river-link promise is a potent campaign promise: water equals votes. Conversely, any backlash (environment protests, displacements) can be downplayed as opposition propaganda or “Ravana’s narrations,” as political operatives call it. Star faces like PM Modi or Environment Minister Yadav photo-op with the site (and tribals in the background, suitably placated) serve the incumbent well.

On the financial side, the construction contracts and suppliers (think big dam builders, cement companies, dredgers) stand to profit from this ₹44k crore spending spree. Local politicians who secure contracts or slush jobs for voters will cultivate their client bases. Even international image counts: India can tout its vision of “National Water Grid”. But the dirty secret is that this “bounty” might mainly flow to engineering firms and hidden pockets, rather than thirsty farmers.

We should not jump to purely cynical conclusions; perhaps this is also a genuine belief in central planning (Vajpayee-era heritage). But the opacity is telling. Official figures of trees felled and families displaced come from Right-to-Information replies or Parliamentary Q&A. Meanwhile, when pressed, the government just repeats claims of prosperity, ignoring demands for independent audits. One could say: if Ken-Betwa succeeds, those winners are everyone – except critics. If it fails (hydrology wrong, reservoir underfilled, ecologies ruined), the winners may well be the very same: contractors who already got paid, and politicians with a campaign tale to tell (plan was “implemented in letter”), while the disadvantaged (tribals, ecosystems, future generations) bear the consequences.

The Unanswered Questions and Outlook

After four years, Ken-Betwa raises more questions than it answers. Will 62 lakh people truly get guaranteed water, or just an IRS-style promise that vanishes by summer? Where exactly will the displaced tribals be rehoused? (State rehab schemes promise a cash package, but tribals report it’s insufficient and unilaterally defined.) How will 17,000 trees replaced (if at all), especially millions more in watershed lost? And as climate patterns shift, will the rivers even behave like the planners assume?

The Central govt insists that all clearances are done and safeguards are in place – but it cannot dodge the inconvenient truths: independent experts warn that hydrology doesn’t support this scale, environmentalists warn of “irreversible harm”, and academic papers warn of disturbing monsoon impacts. The entire river-linking concept is becoming contested: even some state governments (including water-abundant ones) quietly fret that their future flows might be low-balled if interlinking is prioritized.

In the coming months, as dams begin to rise and channels dig, Bundelkhanders will see if water flows through them or if their villages drown. If the money and engineering become tangible (i.e. reservoirs actually fill in monsoons), some livelihood might improve. But if local complaints continue to be ignored, or if tributaries run dry, the project will be remembered less as “national importance” and more as a political vanity project that offered much hope but delivered more heartache. After all, linking rivers is one of the boldest ideas on paper – but in the climate-torn realities of 21st century India, it may turn into a cautionary tale of hubris.