The Ambani-ONGC Gas Game: A Billion-Dollar Fueling Of Power And Loopholes

Does big business have the muscle to bend the rules?

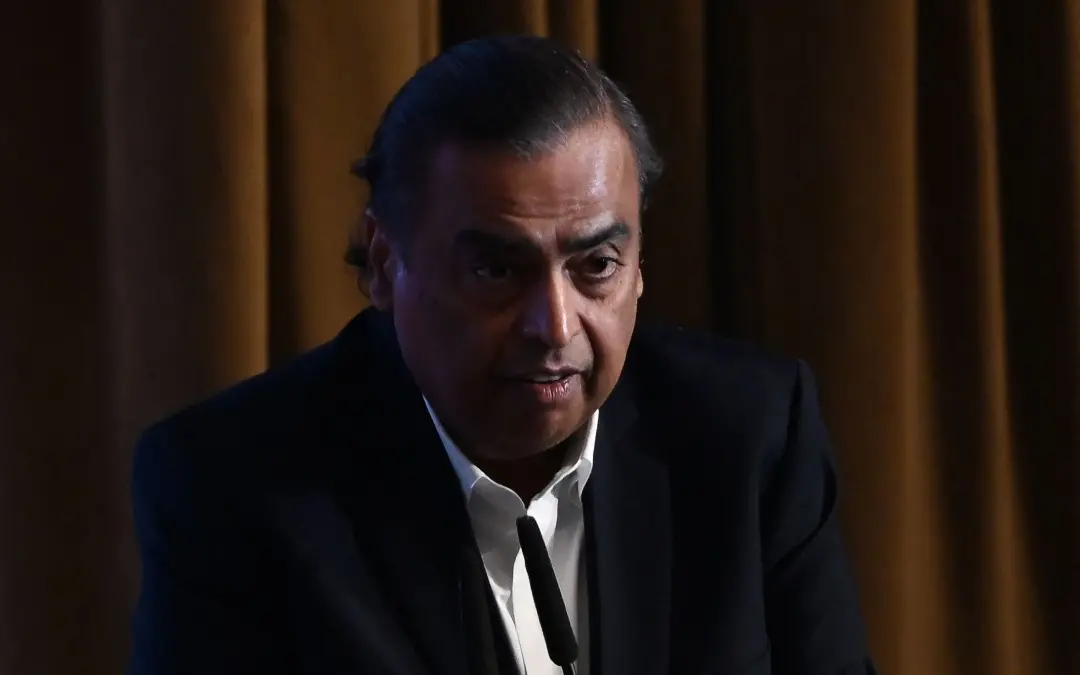

Welcome to the saga that plays out far away in the Krishna-Godavari basin, one of India’s richest offshore gas regions. This saga has all the ingredients of a modern soap: powerful industrialists, government investigators, big loans, and the age-old question of who really owns the fuel in the ground. On one side stands India’s oil behemoth, Reliance Industries Ltd (RIL), led by Mukesh Ambani. On the other stands the public Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC). And between them flows a controversy worth over $1.5 to $2.8 billion, enough to light up entire regions for decades.

The dispute, technically known as a “gas migration” or “unitisation” case, dates back over a decade. In the year 2000, under the government’s New Exploration Licensing Policy (NELP), the KG-D6 block (KG-DWN-98/3), a deep-sea gas field in the Bay of Bengal was auctioned to a consortium led by RIL (and its later partner Niko Resources). Reliance began pumping gas from KG-D6 in 2009, years before ONGC started operations in the adjacent KG-D5 and Godavari blocks (the latter awarded to ONGC in 1997).

In such subterranean fields, neighbouring reservoirs can connect unexpectedly. In 2013, ONGC scientists spotted something disturbing; the gas levels in ONGC’s wells were not behaving normally. It looked as if Reliance’s wells were siphoning gas that underlay ONGC’s blocks. In lay terms, gas was migrating underground from ONGC’s acreage into Reliance’s wells.

ONGC raised the alarm. It first asked the Directorate General of Hydrocarbons (the regulator) for data, then publicly admitted that “anomalous” flows suggested reservoir connectivity. By mid-2013, ONGC filed a petition in Delhi’s High Court seeking compensation for lost gas. Almost predictably, this news leaked and hit the media, turning “Unit KG-D6” into a household term.

Who could blame ONGC? If Reliance, having started first, had quietly drained away ONGC’s bounty, the state-owned company stood to lose billions in resource value. But was there ‘draining’, or was it a natural phenomenon?

Reliance insisted the gas was migratory by nature, meaning it naturally flowed across the porous rock, granting them a lawful claim. ONGC shouted foul that if gas from one field flows into another, they deserved restitution from the one exploiting it.

A bitter legal war ensued. ONGC commissioned a detailed study by independent expert DeGolyer and MacNaughton (D&M) in 2015. The conclusion was that the reservoirs were connected and “gas had indeed migrated” from ONGC’s block into Reliance’s. In other words, Reliance’s rigs had sucked up ONGC’s gas. Next, the government itself convened a panel under former Delhi HC Chief Justice Ajit Prakash Shah.

This committee threw out any claim of outright theft but still ruled that Reliance had benefited unfairly. Since Reliance’s KG block had yielded roughly $1.7 billion worth of gas that should have belonged to ONGC, the government declared that RIL should pay back $1.55 billion in “restitution”. (One might call this the Ambani family getting their oil soaked in, and the government demanding their cut.)

Reliance fought back, not in court but in arbitration, a parallel legal track. In 2018, a friendly international tribunal ruled in Reliance’s favour. Essentially, the arbitrators said (pun intended)- Sorry, India, you can’t make Reliance pay – it’s Reliance’s gas, since they were producing it under the permits they held. The award went so far as to grant compensation to Reliance (a puzzling twist in media reports), effectively wiping out the government’s claim. Reliance breathed a sigh of relief and started boasting that the case was settled.

But the Indian government refused to give up. They went to the Delhi High Court. In May 2023 a single judge shockingly upheld the arbitration award. In bureaucratic jargon, the court said the tribunal’s view was a “possible view” and did not offend public policy. In plain terms, it meant Reliance had won again. The onslaught of demands seemed to be ending.

Enter Twist II: In February 2025, a full division bench of the Delhi High Court did an about-face. It set aside the earlier May 2023 order, branding the arbitration award “contrary to settled law” and against public policy. Suddenly, the government was back in the game. In a blow to Ambani’s empire, the bench effectively agreed that the arbitrators had erred. While Reliance officials were reportedly likely to appeal to the Supreme Court, for the moment, the ruling stands that Reliance might owe money back to India.

And how much money? Here’s where the figures spiral into the stratosphere. Initially, the Shah committee’s $1.55 billion demand was the headline number. But now, with interest and penalties, the Petron ministry has slapped a whopping $2.81 billion demand notice on Reliance and its partners. That sum lumps in the interest on the unpaid share (almost $175 million reported) to the original $1.55b, plus potential fines. It is, by one estimate, about Rs. 2.8 lakh crores, or nearly a year’s entire budget of some Indian states. Imagine if Ambani’s companies are suddenly on the hook for an amount that could fund scores of highways, or several years of rural development, or, for that matter, a presidential election campaign.

No surprise, Reliance’s official statement was defiant. In an exchange filing, the company said it has been “legally advised” that the Delhi Court’s demand and judgment are unsustainable, and that it will challenge both up to the Supreme Court. A routine PR line about “no expected liability” now doubles as a promise to dig in for one more fight. After all, they argue, the DHC has overturned the tribunal only on a narrow technicality of law, and in the mean time, this pending appeal means “no money will actually be paid until the case is finally decided.”

Yet critics are having none of it. They note that Reliance and the Ambani family have for years been among the most powerful players in India’s political economy. Is it mere coincidence that Reliance first won two rounds of arbitration in distant Singapore, then won the High Court in 2023, and only lost when a fresh panel was empanelled under a different bench?

Skeptics point out that government ministers and former mandarins once took top Reliance salaries or seats on Ambani’s boards. They suggest that Reliance may have exploited loopholes and leverage, i.e., the complexity of international arbitration, a sympathetic judge, or backchannels to stall actions until the political climate favoured them. After all, Reliance did manage to get the case dismissed repeatedly over the years, even as evidence piled up.

Indeed, even the legal record can be read as a slow-motion cat-and-mouse game. When ONGC first filed a writ, the court didn’t punish Reliance immediately; it simply told the government to investigate and decide. The Shah panel found nothing criminal, but it did outline an astronomically large restitution. Reliance then “arbitrated and won” (in its favour) before the government even moved.

The Ministry kept pressing, but each time it seemed to run into legal roadblocks. In 2016, it issued the $1.55b claim; arbitrators threw it out. In 2023, a single judge sealed Reliance’s victory. The demand of $2.81b only came after the division bench turned the tide in 2025. Over eight years, Reliance skillfully navigated between tribunals and courts, perhaps hoping that with each passing ruling, the outrage (and pressure) would fade.

Meanwhile, a separate front has opened. In November 2025, an activist petition in the Bombay High Court demanded a CBI criminal probe into Reliance and Mukesh Ambani himself. The petitioner, Jitendra Maru, alleged a “massive organised fraud” from 2004–2013, accusing RIL of illegally drilling into ONGC’s wells and siphoning gas worth over $1.55 billion. He cited the D&M and Shah findings as evidence, and even got the court to issue notices to the CBI and Union of India to investigate. If such a probe were to go ahead, it would mark a seismic escalation, crossing from contractual compensation into criminal liability.

Reliance’s defense, on file, is the same as ever, that the gas was “migratory,” and digging at the reservoir edge is legal. (That it took an independent D&M study to show RIL “tapped gas without authorization” is an inconvenient fact.) But for millions of ordinary Indians, these distinctions are abstruse. They see a petrol pump operator selling fuel at one location, while people pay for it thinking it came from elsewhere. That churned the voters in some street cafes that how can we be asked to pay for this oil-drainage stunt?

Beneath the data and contracts lies a stark question of power- does big business have the muscle to bend the rules? For years, Reliance enjoyed a reputation of having virtually any entitlement at its fingertips. It mounted a years-long challenge in arbitration. Even when the government’s interest on the gas pile grew to Rs. 7,887 crores (as the Shah report noted), no punitive fine was immediately enforced.

The appellate route, of first arbitration, then high court, meant Reliance spent years not paying a rupee, all the while continuing to sell their KG-D6 gas. Well, this is not a single case, where Ambanis have exploited the loopholes and taken advantage by dodging the taxes, they have done it earlier as well. Each delay meant more profit and interest for them, and more frustration for ONGC.

As the Bombay HC petition hints, many ordinary observers smell a whiff of privilege. Why else would such a colossal theft allegation linger unresolved for over a decade? And why was no action taken when an ostensibly valid claim was ignored? These lines of questioning echo a familiar theme in critics’ pens; does corporate clout allow Ambani’s firm to navigate legal loopholes that small players could not? Reliance will argue this is a fair legal fight. Skeptics will say the scales were tilted. The truth probably lies in between where powerful companies do have resources to hire top lawyers and lobby quietly, and they usually survive until the system bleeps them out.

For now, however, one thing is clear, that the courts have given India’s government a lifeline. The February 2025 judgment marks the first time an Indian tribunal put the onus back on Reliance to justify its billions of gains. “We are setting aside the arbitral award, as it is contrary to settled position of law,” read the Feb 15 order. The fight now surely moves to the Supreme Court, where Reliance’s lawyers are said to be polishing their arguments. Either way, this case is far from over.

In this gas game, the losers so far have been ONGC and the taxpayers. ONGC’s staff first blew the whistle, only to see years of legal wrangling. With each passing year, ONGC’s reservoir quietly shrank while bills and analysis mounted on a shelf. Now the government too has to pick up the tab for investigating and litigating. And if Reliance escapes having to pay, it will be a bitter admission that no legal warp is too big for India’s richest.

Yet this saga also represents something more ominous for Indian democracy; where a test of whether rule of law truly applies at the highest levels. If Ambani’s empire can use its clout or the slowness of courts to buy time, what message does that send to ordinary citizens and smaller businesses? Already, dozens of bankers, contractors and small scientists are wondering if they, too, might one day need political shelter to safeguard their interests.

The tale is not finished, but in the interim it’s clear to see who’s been “drinking the milkshake” here. The phrase comes from There Will Be Blood, and it fits all too well: if RIL’s rigs could stretch a metaphorical straw to their neighbour’s reservoir, Reliance drank up the gas while ONGC got a dry well. Whether the judiciary will force Ambani to return a part of that drink remains uncertain, but at least some hope has bubbled to the top.

In the end, the Ambani-ONGC gas dispute is not just an arcane oil story – it’s a snapshot of power dynamics. It exposes how the country’s richest group can parry well-funded accusations with legal finesse. It raises uneasy questions about regulatory oversight, since even the regulatory arm (DGH) was apparently unaware of the connectivity when approving Reliance’s plans. And it underscores how political change can only go so far when the courts and arbiters are navigating these waterlogged depths.

Whether through appeals or protests, the government and ONGC are clearly not letting go. But until the final chapter is written, perhaps high up in the Supreme Court, this game will continue to be played out with India’s energy, economy and rule-of-law watching anxiously. If the common man is left to foot the bill, or worse, to view this as “business as usual,” then the powerful will keep asking, “how do you like your milkshake?”, and hoping the answer is still firmly in their own cup.