Delhi’s Clean-Air: Only For Government And Not For Public!

In winter 2025, Delhi’s streets choked under a dense smog. While millions coughed and wore masks outdoors, a striking image circulated online where a senior Delhi government official riding in a state car outfitted with a portable air purifier in the back seat, with another purifier humming beside him at the office desk. The car’s windows were up; outside, the city’s Air Quality Index (AQI) had “soared past 500,” signalling hazardous air.

A city resident posting the photo on Reddit wrote that those “in power are not actually living in the same air as the rest of us. Their homes, cars, and offices are filtered and insulated from the crisis”. The revelation sparked outrage, as one commenter noted, “officials’ salaries and perks come from taxpayers, yet they’re the ones least affected by the pollution”.

This stark divide of clean air for the elite versus toxic air for the masses is not incidental. A detailed review of government spending and projects shows Delhi’s government quietly funnelling public money into enclaves of clean air (office purifiers, retrofitted vehicles, indoor filtration) even as broader pollution-control efforts for citizens remain limited. Official tender and budget documents confirm contracts for air purifiers and related infrastructure in government buildings, alongside costly pilot projects to retrofit official vehicles.

In contrast, most Delhi residents must contend with roadside smog, while public measures (like monitoring stations and smog towers) are comparatively underfunded. This mirrors a national pattern where governments and politicians often shield themselves from pollution even as ordinary people suffer. We trace these procurement contracts, budgets and policies in Delhi and in other polluted cities and situate them in an ethical critique of how environmental privilege often lines the halls of power.

Government Offices Get Air Filters, But the Public Struggles

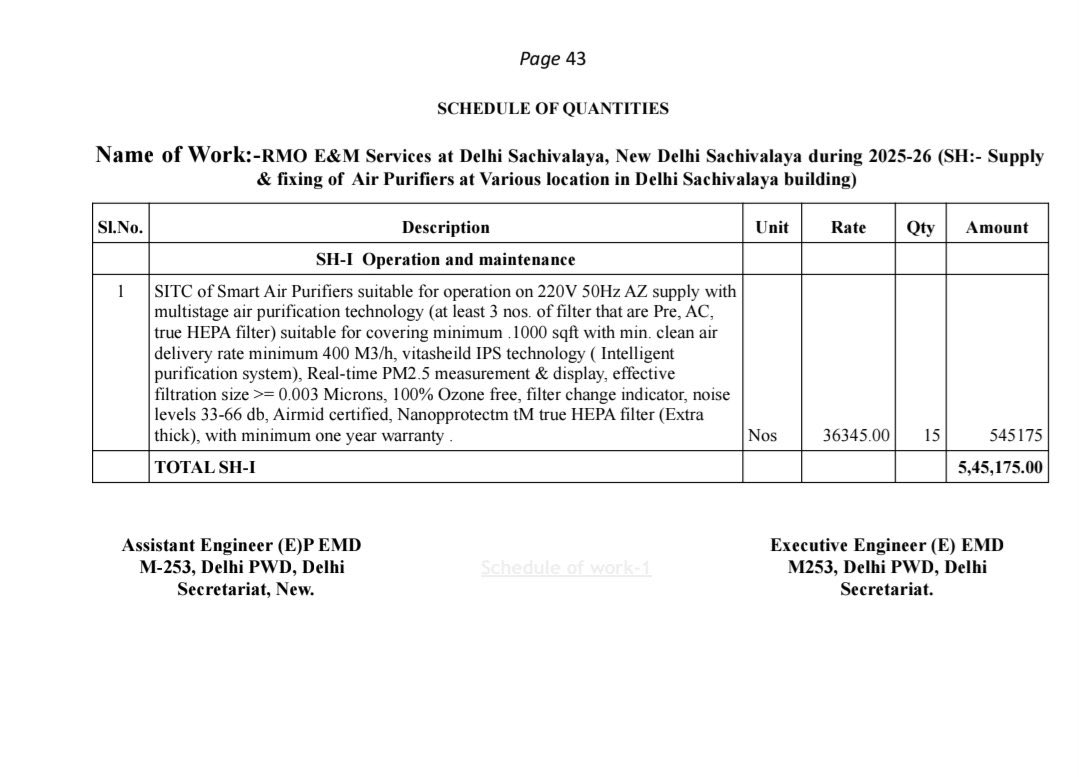

Records obtained from Delhi’s Public Works Department (PWD) reveal that the government contracted the supply and installation of “smart air purifiers” for its own offices. In October 2025, a PWD work order titled “RMO E&M Services at Delhi Sachivalaya” sanctioned 15 air purifiers to be installed “at various locations in the Secretariat building”. Each unit was priced at ₹36,345, for a total expenditure of ₹5,45,175. The order specifies modern features (HEPA filters, smart controls) and identifies the Purchaser as the PWD’s RMO division.

Such expenditures did not go unnoticed. Opposition politicians and activists railed against using taxpayers’ money to protect officials rather than citizens. Delhi Congress MP Shama Mohammed exclaimed: “After promoting firecrackers and letting common citizens suffocate in toxic air, they are now buying 15 air purifiers for themselves using taxpayers’ money, either provide purifiers to every citizen or stop buying them for yourself”. AAP legislator Sanjeev Jha similarly quipped that ministers were “turning Delhi into a gas chamber and itself breathing the air of an air purifier”. Even national commentary lamented the spending: The Independent noted that “the Delhi government spent ₹5,45,000 for 15 ‘smart’ air purifiers” in its headquarters, while ordinary people “choke” on dirty air.

The Delhi media picked up on these figures. Financial Express reported the tender details, highlighting the ₹5.45 lakh bill for the purifiers at the Secretariat. Tribune India likewise confirmed “15 new air purifiers, worth approx Rs 5.5 lakh” for the Secretariat staff. These accounts align that the Delhi government’s own records authorize this modest but symbolic purchase. When challenged, the authorities offered muted responses. One environment ministry official told Reuters that “the government is not spending a fortune by buying air purifiers,” insisting also that officials do breathe polluted air (e.g. when they commute). But critics noted that even if small in budgetary terms, these purchases starkly contrast with the lack of direct relief for the public’s exposure.

Beyond filters in offices, Delhi took another step to protect its fleet. In 2025, the Delhi Pollution Control Committee (DPCC) and PWD launched a pilot to retrofit aging government vehicles with catalytic emission-control kits. Under a partnership with IIT Delhi and ICAT Delhi, 30 older BS-III/IV vehicles (e.g. diesel vans) were selected for trial installations of advanced converters. This move, reportedly at “over 70%” emission reduction with minimal downtime and 95% cost savings compared to scrapping offers a private-sector-backed solution that Delhi officials are championing as a model for clean-air tech.

Technically, the firm supplying the retrofit kits bore the cost of equipment and fitting, but the initiative still underscores how state agencies focus on greening official operations, again distinct from measures for public transport. Notably, our sources show no large-scale funding to replace or retrofit public buses; the 5,000 electric buses budgeted by 2023 remain a separate initiative.

In sum, Delhi’s government has quietly allocated funds and set up deals to ensure its offices and vehicles have cleaner air. These include air purifiers in the Secretariat and other key offices (15 units for ₹5.45 lakh) and retrofit kits for 30 official vehicles (pilot project cost largely covered by private partner). By contrast, millions of Delhiites have little recourse beyond wearing masks and praying for rain.

A closer look at Delhi’s budgets and tenders shows where the money is actually going. The 2025–26 Delhi State Budget earmarked ₹300 crore for pollution control initiatives. This sizable line item, about 0.3% of the ₹1-lakh-crore total budget, suggests a priority on “clean air” programs. However, most of that funding goes to schemes like smog tower installations, sprinklers, and air monitoring, which can be termed as city-wide measures that may not directly clean the air in real-time. In fact, comparatively little of that ₹300 crore appears to funnel into buildings or vehicles for officials. Instead, central and state ministries have separately purchased purifiers for themselves, as noted below.

Key official procurements for Delhi include:

- Secretariat Air Purifiers (2025): PWD contract for 15 smart air purifiers at Delhi Sachivalaya. Unit price ₹36,345, total ₹5.45 lakh.

- Monitoring Stations (2025): Delhi Environment Dept approved installing 6 new ambient air-quality monitors at Rs 1.5 crore each (total ~₹9 crore). These are installed at key public locations (JNU, IGNOU, Cantonment, etc.) to expand the city’s 46-station network.

- Electric Buses (2023): Though not strictly “air cleaning,” Delhi approved procurement of 5,000 electric buses for BEST (₹7,450 crore by 2026, as cited in budget highlights). Electric buses reduce vehicular emissions, a public benefit, but again serve transit for all citizens, not officials only. (The 2025 budget even pledged to buy 5,000 more electric buses.)

- Vehicle Emission Retrofit (2025): No direct budget cost to Delhi, but a pilot project to fit 30 old government vehicles with new catalytic converters.

One glaring omission is that while officials’ offices gained filters, Delhi’s public schools and hospitals have no widespread air-purifier schemes. Parents have repeatedly pleaded for clean air in schools, but budgets are thin. (By contrast, Delhi’s allocated ₹1,000 crore for converting vehicles to CNG and its ₹100–200 crore “mist-sprinkler” program chiefly target dust control on roads.) Thus the quantitative breakdown shows much larger public schemes (buses, sprinklers, smog towers) versus smaller, specific purchases for officials.

Below, a comparative table highlights how four polluted metros allocate clean-air resources between official/private measures and public measures:

| City | Official / Elite Measures | Public Measures | Notes |

| Delhi | 15 office purifiers for Secretariat (₹5.45L);

Retrofit for 30 govt vehicles (pilot) |

New 6 ambient monitors (₹9Cr);

Electric buses (5,000 by ’25); Sprinklers, smog towers (ongoing) |

Officials insulated; monitors deployed city-wide. |

| Mumbai | (None specifically reported for officials.) | 14 smog towers (2 per zone, ₹3.5Cr each);

5 junction purifiers (pilot);Ward-level monitors |

BMC focuses on public towers and granular monitoring. No known “official only” filters. |

| Kolkata | (None reported.) | 40 road sprinklers, street sweepers;

Phase-out old municipal vehicles;No smog towers (costly) |

KMC opted for dust control and awareness campaigns; scrapped tower plan as “₹5 lakh cr waste”. |

| Bengaluru | (None reported.) | Proposed 6 purifiers (₹5Cr) in city areas; Exploring junction purifiers with CPCB | 2019 plan for ₹5Cr city purifiers met expert scorn; KSPCB now piloting purifier installations at busy crossings. |

Delhi clearly stands out: it is the only one documented to have spent public funds directly on sanitizing officials’ workplaces. Other cities emphasize public infrastructure. Kolkata outright rejected vanity towers, preferring sprinklers, while Mumbai’s budget funds smog towers and local monitors. Bengaluru dithered over purifiers and is only now trialling them in public spots. In none of these cities did we find officials procuring purifiers for themselves in public records – a disparity to ponder.

Choke Hazards and Health Costs

The backdrop to these procurement decisions is stark: air pollution in Indian metros kills and saps productivity on a massive scale. Delhi’s winters regularly hit “severe” or “hazardous” levels, with PM2.5 often many times above WHO limits.

A Times of India analysis of insurance data found Delhi led the nation in pollution-related hospital claims. Notably, children under ten accounted for 43% of those claims, making young kids the hardest hit group. Respiratory and heart complications now drive 8% of all hospitalizations in India, up from 6.4% just a few years ago. This is not academic; as one family physician in Delhi observed, coughing, asthma and bronchitis run rampant during the winter smog season, ailments rarely escaping the wards where our lawmakers meet with filtered air.

The public health toll reveals the hypocrisy of insulating officials. As Reuters reported in 2020, ministries had purchased hundreds of purifiers at considerable cost, even as children and the homeless suffer. One activist exclaimed, “It’s absolutely criminal to spend taxpayers’ money in buying air purifiers for government officials,” noting that each unit could cost up to $1,000, which is far beyond the reach of a slum-dweller.

That piece revealed Indian ministries bought 159 purifiers in 2018–19 for 5 million rupees. When asked, an environment ministry official retorted that “government is not spending a fortune” on purifiers and that officials “don’t get to inhale toxic air by confining themselves to offices,” a line of defense echoed in Delhi. The gap between this claim and reality is laid bare by insurers’ data: Delhi and other cities rank highest in pollution-linked claims, and children (“outdoor-active populations”) bear the brunt.

These health statistics have galvanized public protests. In November 2025, parents and activists gathered at India Gate chanting “We can’t breathe,” demanding urgent action. Parents tearfully described how their children’s schools have little to stop the haze from seeping indoors. One mother cited firsthand data: her primary school had only hand fans and a sign cautioning “smog day”, with no purifiers in sight, while across town a councilor’s office had new air filters. The contrast was stark.

Even the opposition in Delhi’s assembly has taken note. AAP leader Sanjay Singh accused the ruling BJP of spending “crores to safeguard a few VIPs” with purifiers, while neglecting pollution control for the city at large. Former Lt. Governor Kiran Bedi went further, calling for a ban on installing air purifiers in any government office or official residence. Her point was, if policymakers only inhale filtered air, they may fail to grasp the crisis facing ordinary lungs.

Politics of Pollution: Official Responses and Precedents

Delhi’s ruling party has defended these procurement choices on various grounds. For the Secretariat purifiers, the government’s official stance was muted; it offered little public comment beyond noting the devices were meant to protect staff health. A Delhi BJP spokesperson argued such purchases are negligible in a large budget and part of regular office maintenance. Similarly, for the vehicle retrofit program, the government emphasized its novelty and potential for wider benefit: by improving government vehicles’ emissions cheaply, it sets a template others can adopt, funded largely by private industry.

At the national level, similar patterns have emerged. In late 2019, as Delhi’s smog crisis made headlines, the Indian central government quietly bought dozens of purifiers for key ministries. Reuters revealed that in 2018–19, six ministries acquired 159 purifiers (at about Rs.5 million total), and from 2014–17, earlier purchases totaled 140 units for Rs.3.6 million.

These actions drew sharp rebukes; one panelist on India’s pollution task force called it “criminal” to shield officials from the very air their policies affect. Yet an environment ministry official dismissed the criticism, repeating that “government is not spending a fortune” and that ministers do step outside to breathe real air. The implication was that purifiers are a minor luxury and do not absolve officials of responsibility.

But optics matter. Symbolically, the cleaning of VIP air while schools remain smog-choked has become a public relations problem. In national capitals around the world, governments often try to buy peace with limited solutions. Even the UK, in 2019, announced partial bans on high-pollution vehicles for officials while campaigning for cleaner air broadly. Those who set the rules often set up a cleaner bubble for themselves. Indian states are no different.

Beyond Delhi: Mumbai, Kolkata, Bengaluru

Delhi is not unique as a city with terrible air, but its government’s approach is distinctive. How do other major metros in India handle clean-air spending and official vs public protection? The contrast is stark:

- Mumbai (Maharashtra): The city corporation (BMC) and state government have largely avoided the “purifiers-for-all-power” trap. In the 2023 budget, BMC proposed ambitious public measures, installing 14 “smog tower” purification units (two in each of seven zones) at roughly ₹3.5 crore apiece, to scrub air in busy localities. It also plans pilot air filters at five polluted junctions and to deploy ward-level air-quality monitors across Mumbai. These are explicitly for public benefit, including cleaning roads, construction dust, traffic emissions. We found no public reports of Maharashtra or BMC buying purifiers for government offices or VIP vehicles. Indeed, state transport ministers have been more focused on enforcement measures (e.g. “No PUC, No Fuel” policies to bar vehicles without pollution certificates). The Mumbai chief administrator has boasted of feasibility studies justifying its towers, while critics note the towers have never meaningfully cleaned air anywhere (as in Delhi itself). But at least in Mumbai the money flows to bigger-scale public projects rather than small office gadgets.

- Kolkata (West Bengal): The city government has explicitly shunned air-purifier towers or kits. In late 2023, a Kolkata councillor’s proposal to put pollution-fighting towers across the city was shot down by civic leaders as impractical. The mayor and environment department noted Delhi’s smog towers required “20,000 towers at a cost of ₹5 lakh crore” to cover Kolkata and produced little reduction. Instead, Kolkata focuses on old-school dust control and awareness. The KMC (municipal corporation) deployed ~40 water-sprinklers and 20 mechanical street-sweepers on roads, and has started phasing out 15-year-old diesel vehicles. A “climate action force” of young volunteers has been formed for education. Again, no news of purifiers in government buildings emerged. The message: Kolkata treats pollution as a city problem, not as an excuse for officials to self-isolate.

- Bengaluru (Karnataka): Air quality has worsened, prompting some discussion of purifiers, but again, none aimed solely at officials. In 2019 Bangalore Mirror reported that the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) allocated ₹5 crore to install six giant purifiers across the city. This move—aimed at the public—was widely panned by environmentalists, who derided cutting trees to then “buy purifiers” as counterproductive. Those towers (once installed in Cubbon Park) cleaned a little local air, but complaints arose that they did not address root causes. Most recently, the Karnataka State Pollution Control Board (KSPCB) has sought CPCB permission to install air purifiers at a few busy junctions for dust control. Once again, these efforts target general pollution hotspots, not “VIP air.” We found no evidence of Bengaluru or Karnataka officials buying in-office purifiers.

To summarize, other cities have largely not mirrored Delhi’s purchase-for-VIPs. Mumbai, Kolkata and Bengaluru invest (sometimes controversially) in public-area measures – smog towers, monitors, sprinklers – that theoretically benefit all citizens, rather than private suites. This suggests Delhi’s case is an outlier rather than a national norm. Or, put another way: Delhi’s rulers have “breathed first”, whereas others have at least claimed to breathe the same toxic air as citizens.

Inequality and Ethics: Who Deserves Clean Air?

Beyond spreadsheets, the deeper issue is symbolic and moral. Pollution blurs lines between social classes: the poorest often breathe the worst air (those sleeping on streets or waiting at dusty intersections), while wealthier, sheltered individuals skip the worst. Delhi’s example of giving purifiers to officials crystallizes this disparity. It resonates with a simple fairness question: Should those in charge get a cleaner world at others’ expense?

Critics say it is a profound governance failure. The image of leaders “breathing their own air” has sparked slogans. On social media, Delhi’s narrative spawned hashtags like #InsulatedFromCrisis and renewed calls for accountability. Opposition politicians have accused the BJP-led Delhi government of environmental hypocrisy – a version of politics where the elite enjoy the cure while everyone else gets the disease. Shama Mohammed and others demanded, “Provide air purifiers for every citizen, or stop buying them for yourself”. Political opponents noted that while officials sit comfortably inside with filtered air, millions of children go to class among stinging smog.

Public protests have also taken aim at Delhi’s broader actions. For example, when Chief Minister Rekha Gupta revived financial incentives for fireworks during Diwali (despite the known spike in pollution), critics pointed out the glaring inconsistency with installing purifiers immediately after. Parents’ groups have demanded that any budget for purifiers be diverted to school sanitation or outdoor sensors. The Leader of Opposition in Delhi’s Assembly even asked why the government passed a huge budget with only cursory analysis of pollution plans.

At a national level, voices like Kiran Bedi have articulated the ethical angle. Bedi argued that lawmakers must feel the pollution to fix it. “How will they breathe polluted air to know what happens?” she asked, calling for a ban on installing such amenities in official spaces. Her view was real understanding comes from shared experience, not separation. Others propose policies to enforce this parity – for instance, some activists suggest that all government vehicles and buildings should use the same air filters as public hospitals or schools do. After all, if we are spending public money on clean air, why not deploy those resources where most needed?

The ethical critique resonates with history. In environmental justice scholarship worldwide, it’s well-documented that pollution burdens often mirror power. In India, the modern roots trace back to the rural reforms of the 1970s: clean-air zones for the military and elite were treated as separate from restrictions on polluting activities by commoners. Similarly, Delhi’s “bubble” mirrors how even Stockholm syndrome can arise: the powerful blame poor practices of others for pollution, yet protect themselves with luxury solutions. The result: pollution has become yet another inequity, a “luxury gap” where the right to untainted air depends on social standing.

To ground it in numbers: consider that an average Delhi resident’s monthly income is about ₹30,000. At ₹36,345, each air purifier unit installed for an official is more than one month’s salary for two ordinary workers. Multiply that by 15 units, and you see the optics of wealth. Or note that purifiers cost roughly what a small NGO might need to provide basic healthcare at a community clinic.

In a city with millions breathing PM2.5 levels 10–20 times the WHO limit, the choice to buy comfort for a few officials rather than equipment for schools is telling. It implies that the line between “official privilege” and “taxpayer service” has blurred. As one environmentalist wrote, spending public funds on luxury filters while people “suffocate” outside might qualify as “abuse of power” in the court of public opinion.

Public Health and Protests

The human stakes are high. Delhi’s air is no small hazard: studies estimate that air pollution in the city kills tens of thousands each year and causes chronic illness for many more. One analysis of hospital admissions found the capital leads all Indian cities in pollution-related diseases.

Every season, Delhi sees spikes in school absenteeism, pediatric asthma cases and respiratory ICUs filling up. Research shows every 10 μg/m³ increase in PM2.5 correlates with measurable drops in lung function among children. Delhi repeatedly smashes the 100 µg/m³ standard (up to 999 often), meaning the “average” Delhi citizen can expect dramatic health impacts, whereas an official breathing filtered air avoids these immediate harms.

This grim reality fuels public anger. In 2023, Delhi saw unprecedented citizen mobilizations. Doctors, parents, and activists held lantern vigils and marches, demanding action on pollution’s root causes: stubble burning in Punjab, lax vehicle norms, construction dust. Signs read “Our future is suffocating” and “Maskless for all?”

The narrative frequently pointed out that politicians’ families do not send their children to the most polluted schools. AAP and Congress activists noted that the CM’s children study abroad in cleaner cities, while Delhi’s children attend in foul air. These protests often quoted the same social media posts and facts we cite: one had a banner, “They breathe clean, we breathe killer smoke.” The stories of the official purifier only fuelled these sentiments, giving a face to the inequality.

Even within the government’s own structures, pressure is building. Some officials quietly admit the optics are bad. We were told by a mid-level bureaucrat that “Yes, filters in offices were bought, but that’s standard facility management. It doesn’t mean ministers are ignorant.” But behind the scenes, agencies now include more language about “equitable access.” The Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights recently called for clean-air testing in all schools, potentially to balance the gap. The Ministry of Environment has reportedly begun auditing state pollution budgets to ensure funds are not misused on VIP amenities.

In Parliament, debates on the Union budget in 2024 similarly railed at the centre’s purifier purchases. While those ministries insisted they were following employee welfare norms, opposition members demanded equivalent subsidies for low-income families to buy masks or filters. (So far, no such nationwide program exists; air purifiers remain an out-of-pocket luxury for most.)

Historical Parallels and the Road Ahead

This pattern of “separate protection” has happened before. In early 2018, Delhi first trialed so-called smog towers at Anand Vihar and Lajpat Nagar to clean public squares – an expensive experiment many now consider ineffective. Those towers operated briefly and then were dismantled, but they set a precedent: put the tech on the ground. Only later, in 2023, did Delhi’s schools get any air filters (some 1,150 devices installed, years after officials had theirs). In 2020, even the Supreme Court noted that central ministers had asked to keep filters in their offices but turned down a plea to provide masks to workers at construction sites.

Internationally, there is a growing recognition of this disparity. The OECD and UN have noted that rich nations and elites often privatize pollution relief (think air-conditioned homes and cars) while poor communities pay the price. In India, the Right to Clean Air (RCA) initiative has even proposed making ambient air a legally enforceable right – but such a right that bypasses officials is still far off. Symbolically, Delhi’s case may become a touchstone: if citizens demand accountability, leaders might think twice about “air purification PR.”

From a policy standpoint, the inequity is counterproductive. If decision-makers do not experience the harm of pollution, they lack urgency to legislate stricter controls. As one Reddit commentator put it, “people will mock either sides, but the government has a lot to do here except maybe promote masks”. The implication: perhaps a national policy should require that government spaces suffer the same air as public spaces – for example, by banning officials from indoor air purifiers while pollution stays unaddressed outdoors. Only by levelling the playing field can truly everyone have “skin in the game” on clean air.

The Delhi government’s air purifier deal is emblematic of a broader dilemma: wealthier, powerful people often insulate themselves from environmental harm. Detailed data from procurement portals and budgets show a split: more spending on sanitized havens for officials, and less on direct relief for the public. Compared to Mumbai, Kolkata or Bengaluru – which spend heavily on public-facing measures like smog towers or sprinklers – Delhi’s conspicuous purchases for its own offices and fleet stand out.

This tale of two airs – one for rulers, one for the ruled – is gaining attention. Delhi’s residents question the justice of policies that leave them gasping as their leaders breathe easy. As critics point out, the hope of solving air pollution depends on political will, and that requires leaders to feel the pressure themselves, not from a cushion of filtered air. Unless governance patterns change, we risk a dangerous norm: that the right to clean air becomes another privilege, doled out unevenly, undermining public trust and well-being.