FDI At 49%: India’s Bold And Risky PSU Bank Pivot. Is Foreign Capital The Answer To India’s PSU Bank Problem?

India is weighing a major rethink of public sector banking, with plans to raise FDI in PSU banks to 49% alongside a broader institutional review. While the move promises fresh capital and global scale, it also risks importing volatility without fixing governance, control, or long-pending disinvestment challenges.

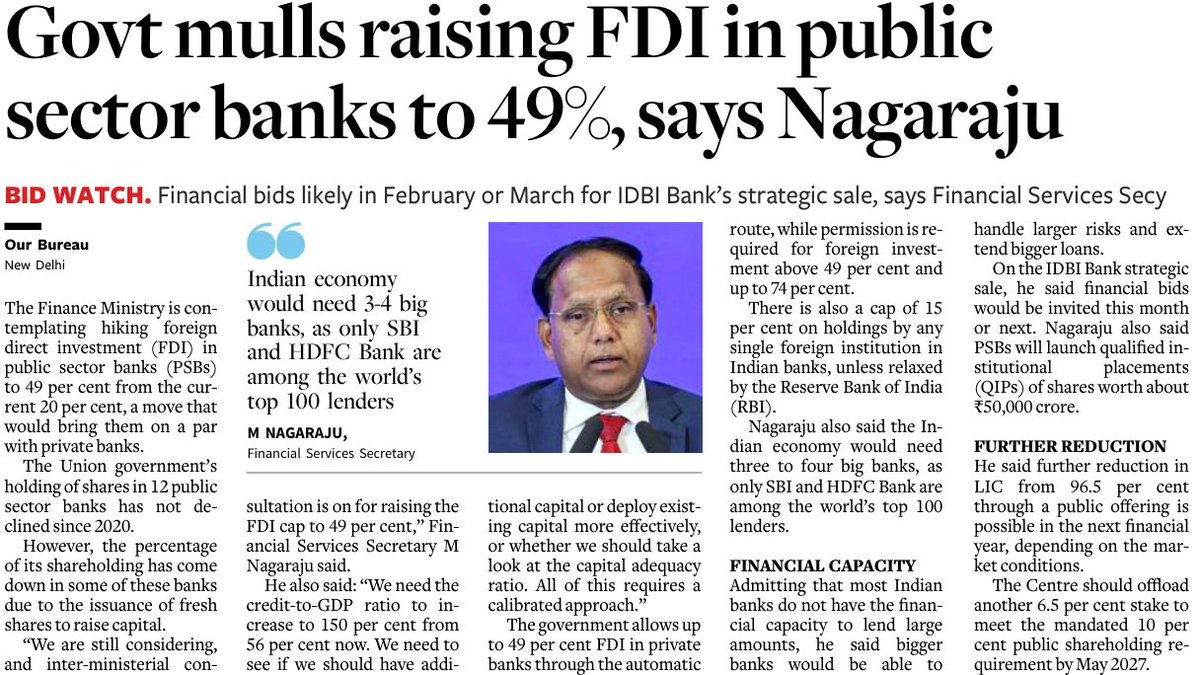

A significant recalibration of India’s banking policy appears to be underway. The government is currently engaged in inter-ministerial consultations to raise the foreign direct investment (FDI) limit in public sector banks (PSBs) from 20% to 49%, according to financial services secretary M. Nagaraju, and as widely reported.

The timing is notable. The remarks follow closely after Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s Budget announcement proposing the creation of a High Level Committee on Banking for Viksit Bharat. Taken together, these developments point to a renewed effort by policymakers to prepare India’s banking system for the scale and complexity demanded by the country’s next growth cycle, as it advances toward becoming the world’s third-largest economy.

This rethink is unfolding at a moment of relative strength for the public banking system. After years marked by stressed assets, repeated capital injections, and governance concerns, PSBs have emerged with cleaner balance sheets, improved asset quality, record profitability, and extensive national reach. A sector once defined by crisis management is now operating from a position of stability.

However, stability alone may no longer be sufficient. India’s economic ambitions are expanding faster than the capacity of its existing financial framework. The government’s long-term development blueprint, articulated through the Viksit Bharat 2047 vision, calls for sustained financing of large-scale projects across infrastructure, renewable energy, manufacturing, logistics, and technology. Meeting these demands requires banks that are not only sound, but also large, well-capitalised, and credible in global markets.

It is against this backdrop that the proposed High Level Committee on Banking is expected to play a pivotal role. The panel is likely to examine the financial system in its entirety – including ownership structures, governance norms, and the feasibility of building fewer but significantly larger banks. The broader objective is to create lenders with balance sheets capable of supporting complex, capital-intensive projects comparable to those financed by leading global institutions.

Over the past few years, the government has already pursued consolidation among public sector banks, reducing their number to 12 through a series of mergers. While further consolidation remains an option, size achieved through mergers alone does not automatically translate into deeper capital pools or international standing. This is where foreign investment is increasingly being viewed as an additional lever.

Why Opening The Door To Foreign Capital Matters

Increasing the FDI limit in PSBs to 49% would mark a clear departure from India’s historically conservative stance on foreign ownership in state-run lenders. While the government plans to retain majority ownership and strategic control, allowing a substantially larger foreign shareholding could broaden access to long-term, non-government capital.

Public sector banks account for more than half of India’s total banking assets, giving them a central role in determining the pace and breadth of credit growth. Their ability to raise capital efficiently is therefore closely linked to the wider economy. Higher foreign ownership thresholds could reduce dependence on periodic government recapitalisation, easing fiscal pressures while enabling banks to expand lending in line with economic needs.

The proposal would also move PSBs closer to the ownership norms that already apply to private banks, where foreign investment of up to 74% is permitted under specified conditions. Aligning public banks more closely with this framework signals an intention to place them on a more level footing in the competition for capital.

Such a shift could attract long-term institutional investors – including global banks, sovereign wealth funds, and pension funds – who bring more than just funding. Exposure to international standards in governance, risk management, and technology could, over time, strengthen operational efficiency and modernisation within public sector banks.

Building Banks For A Globalising Economy

India’s objective of creating at least two banks that can compete on a global scale is closely intertwined with its broader development goals. Financing large green energy projects, smart infrastructure, logistics corridors, and advanced manufacturing ecosystems requires lenders with the capacity to deploy capital over long horizons and absorb complex risks.

Foreign investment can help PSBs expand their balance sheets to meet these requirements while enhancing their credibility in international markets. Better-capitalised banks are more likely to access overseas funding, participate in cross-border financing arrangements, and support Indian firms as they expand beyond domestic borders.

If implemented with care, higher foreign ownership limits could generate wider economic benefits. Greater capital availability can support stronger investment activity, job creation, and productivity growth. Reduced reliance on taxpayer-funded recapitalisation may also allow public resources to be redirected toward social and infrastructure priorities.

Crucially, the move to raise FDI limits is not being framed as an isolated reform. It is part of a broader attempt to reimagine India’s banking system for its transition toward developed-economy status. Alongside institutional review through the High Level Committee, continued consolidation, and an emphasis on governance and efficiency, the proposal reflects an acknowledgement that domestic capital alone may not be sufficient to fund India’s long-term aspirations.

Where The Policy Stands Today

At its core, the government’s approach seeks to widen the capital base of public sector banks while retaining strategic control, in order to align the financial system with the scale of India’s economic ambitions.

Whether this approach can deliver durable reform or whether it merely postpones deeper structural choices – remains an open question. That debate, however, lies ahead.

The Risks Beneath The Headline Reform

Raising FDI and FII limits in public sector banks without parallel reform carries risks that go well beyond market volatility. At its core, the strategy risks importing capital without importing accountability, weakening the public-policy role of PSBs without making them genuinely competitive, postponing hard decisions on governance and disinvestment, and increasing systemic exposure without addressing operational shortcomings.

The issue is not whether foreign capital can enter India’s banking system; it already does. The question is whether the form in which it enters strengthens the system or merely flatters it in the short run.

Passive Foreign Capital Is Not Stable Capital

The most immediate and least discussed risk lies in the nature of the inflows themselves. Much of the capital expected from a higher FDI/FII ceiling is unlikely to be strategic or long-term. Instead, it is expected to be passive, index-linked money, driven by benchmark mechanics rather than conviction.

Global indices such as MSCI determine weights based on available foreign ownership headroom. Raising the cap automatically increases that headroom, forcing index funds to buy PSU bank stocks regardless of fundamentals. While this can lift valuations quickly, the same mechanism works in reverse during global risk-off cycles.

The Reserve Bank of India, across multiple Financial Stability Reports, has repeatedly flagged the destabilising potential of volatile portfolio flows in the banking sector. Banks, unlike other corporates, sit at the centre of the credit cycle. Sudden inflows can inflate balance sheets rapidly, while sudden exits can amplify stress precisely when stability is most needed.

In simple terms, passive capital tends to be generous on the way up and ruthless on the way down. For institutions as large and systemically important as PSBs, that volatility is not a trivial risk.

As things stand today, foreign participation in PSBs remains modest – the largest six state banks had foreign institutional holdings mostly in the single digits as of mid-2025, despite private banks allowing much higher foreign stakes.

This suggests that simply raising the statutory limit may not automatically attract deep foreign capital unless accompanied by governance and control reforms. Even more tellingly, when the government clarified there was no imminent plan to hike the FDI cap, PSU bank stocks slid sharply, indicating how investor sentiment around ownership mechanics can drive volatility independent of fundamentals.

Regulatory constraints also persist, with approvals required for meaningful overseas stakes and voting rights caps still in force, showing that capital access alone does not rewrite governance structures.

Ownership Without Control Creates A Governance Vacuum

The government has made it clear that while ownership limits may be relaxed, control will not be. Voting rights are likely to remain capped at 10%, and government shareholding will stay above 51%.

The result is a structural contradiction. Foreign investors will bear economic risk without possessing meaningful influence over key decisions – from CEO appointments and board composition to lending discipline and risk appetite. Political interference, where it exists, remains untouched.

This produces a worst-of-both-worlds structure: PSBs become less purely state-controlled, raising market expectations, but stop well short of true market governance, leaving accountability diluted. Several analysts have described this model as one that socialises risk while privatising capital volatility – an equilibrium that has historically proven unstable.

Dilution Delays The Real Reform: Disinvestment

There is an uncomfortable reality policymakers have long struggled to confront: India does not require a dozen public sector banks with majority government ownership.

Committees and policy documents over the years – including the PJ Nayak Committee, successive Economic Surveys, and internal deliberations within NITI Aayog – have broadly converged on the same conclusion. Strategic disinvestment in non-core PSBs is unavoidable, with government control best retained in a limited number of systemically critical or development-focused lenders.

Raising FDI limits risks postponing that reckoning. Higher market valuations reduce the urgency for politically difficult reforms. Familiar arguments about protecting national assets resurface. Temporary market comfort replaces structural change.

In this context, foreign capital risks becoming a painkiller; relieving symptoms without addressing the underlying condition.

Public Mandate Versus Foreign Capital Expectations

Public sector banks are not commercial entities in the narrow sense. They are still expected to lend counter-cyclically, support MSMEs during downturns, absorb policy shocks such as farm loan waivers, and maintain branches in regions where profitability is structurally limited.

Foreign investors, even those with a long-term horizon, price these obligations as risks rather than virtues. The tension is unavoidable. It often manifests in persistent valuation discounts, pressure to limit social lending, and frustration over returns that trail private-sector peers.

No amount of capital can resolve this contradiction on its own. It is a political and policy choice, not a financial one.

Uneven Benefits And Market Distortions

Another underappreciated risk lies in how index-driven capital allocates itself. Larger banks – such as State Bank of India – already have substantial foreign ownership and index representation. A higher cap may marginally alter their position.

Smaller PSBs, however, with low existing FII holdings, suddenly gain disproportionate foreign headroom. Index mechanics can funnel capital toward weaker institutions simply because they offer more room for foreign ownership, not because they are stronger or better governed.

Globally, such distortions have often delayed consolidation and prolonged the life of inefficient institutions, complicating eventual restructuring.

Global Precedent Offers Little Comfort

International experience provides sobering lessons. Countries that opened state-owned banks to foreign capital without parallel governance reform – notably parts of Latin America in the 1990s and Eastern Europe in the early 2000s – often experienced a familiar sequence: rapid inflows, stress during global downturns, and eventual forced restructuring or privatisation. The takeaway is consistent: foreign capital works best when control, accountability, and incentives move together. India’s current proposal shifts only one lever.

The Political Economy Risk

As foreign ownership approaches 49%, market sensitivity increases and policy decisions come under greater global scrutiny. Yet government influence over lending and management remains. This combination can create policy paralysis, reputational risk, and heightened sensitivity to global sentiment.

In extreme scenarios, it could even constrain the government’s ability to use PSBs counter-cyclically – the very justification for retaining control in the first place.

What a more credible path could look like

- A stronger strategy would acknowledge these risks upfront:

- Raise FDI limits selectively rather than across the board

- Link higher foreign ownership to clear governance milestones

- Proceed with strategic disinvestment in weaker PSBs

- Retain majority control only in systemically critical lenders

- Fix board vacancies and leadership gaps before inviting large-scale capital