How Delhi Government’s Health System Collapse May Convert Mosquito Borne Diseases To Mortuaries?

Monsoons, Mosquitoes, and a Brewing Disaster

It’s the monsoon season in Delhi, a time when the city’s streets turn into rivers and mosquitoes swarm with deadly intent. Heavy rains have once again pounded Delhi and its satellite city Gurugram, leaving roads waterlogged and traffic in chaos. In early August 2025, an eight-hour downpour submerged major intersections from Dhaula Kuan to Lajpat Nagar, as civic agencies received around 100 complaints of waterlogging in a single day.

Gurugram, the gleaming tech hub, lived up to its infamous moniker #Gurujam as entire upscale communities were marooned in floodwaters. Social media compared the scenes to a modern-day Venice. These sights, however alarming, have become an annual nightmare. Every monsoon, a single bout of heavy rain exposes the gaping holes in Delhi-NCR’s infrastructure, with knee-deep water on roads, stranded vehicles, and even casualties reported.

The flooding is more than just a traffic woe. It is a public health time-bomb. Stagnant water and overflowing drains provide perfect breeding grounds for mosquitoes, the deadliest insects in the world. As experts grimly note, the rainy season is the ideal time for these disease vectors to breed and thrive. In the stagnant cesspools left behind by the rains, incurable mosquito-borne diseases are incubating, threatening to erupt. Delhi’s own Delhi Jal Board has warned that the onset of monsoon creates prime conditions for mosquitoes that carry dengue, chikungunya, malaria etc., urging all agencies to step up anti-mosquito drives. Yet, year after year, the city’s authorities seem overwhelmed and unprepared, lagging woefully in preventing and treating these illnesses.

This year is no exception. By mid-2025, Delhi has already recorded an alarming surge in mosquito-borne infections, 246 cases of dengue and 17 of chikungunya by late July, far higher than the previous years. The capital’s Public Health Department admits it is short-staffed, with half of its mosquito control inspector positions vacant, hampering efforts to contain breeding. Meanwhile, relentless rains have dumped above-average rainfall (over 259 mm in July alone) and caused “lasting waterlogging” across the city, which is a recipe for exploding mosquito populations. “There is little excuse for not doing the basics right,” experts say, yet each monsoon Delhi’s outdated drainage collapses and citizens pay the price.

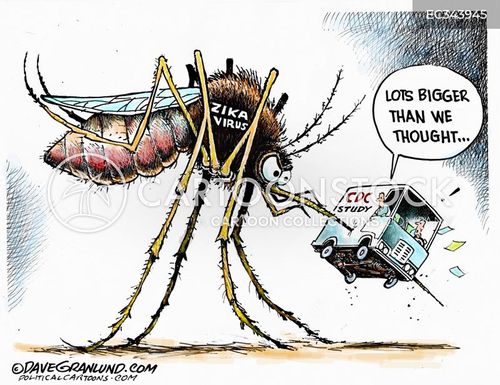

Worse still, the diseases carried by these flood-bred mosquitoes are among the most dangerous and incurable known to medicine. Chikungunya, dengue, Japanese encephalitis, Zika, West Nile, these names strike fear because there are no definitive cures or widely available vaccines. Hospitals can only offer supportive care to manage symptoms while the viruses run their course.

In Delhi, that often means overcrowded wards and panicked families, as health workers scramble to treat high fevers, agonizing pain, or swelling brains with nothing but IV fluids and oxygen. It is a disturbing scenario where the city’s infrastructure is breaking under climate stress, and in the floodwaters breed microscopic killers that break human bodies from the inside. Below, we examine each of these mosquito-borne diseases; how they “break bones” and lives – and how the broken system in Delhi is failing to address them.

Chikungunya: “Bent Over” in Agony

Chikungunya is perhaps the most emblematic of these illnesses. Its very name, from the African Kimakonde language, means “that which bends up,” describing victims contorted in pain. It is a vicious viral disease spread by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, the same day-biting pests that spread dengue and Zika. A single bite from an infected mosquito can unleash sudden high fever and savage joint pain within days. Patients often writhe with “crippling” pain in their joints, sometimes unable to stand upright, hence the “bent over” appearance. Other symptoms include headache, muscle aches, rash, and fatigue, but the defining feature is the excruciating joint inflammation that can last for weeks or months.

There is no cure or specific antiviral treatment for chikungunya; doctors can only offer pain relievers and fever reducers to manage the agony. Most patients fortunately recover within about a week, once the fever breaks. But for a significant many, the nightmare doesn’t end there. The joint pain can linger for months or even years as a chronic disability.

In rare cases, chikungunya leads to severe complications like neurological or heart problems, especially in newborn babies or the elderly with other illnesses. Deaths from chikungunya are rare, but they do occur in the most severe cases or among vulnerable patients. Doctors recall the massive 2016 outbreak in Delhi, when over 4,000 were infected and hospitals saw an unprecedented surge of patients hobbling in on swollen limbs; several elderly patients died from complications that year.

Delhi’s experience with chikungunya underscores the failure of public health preparedness. That 2016 outbreak overwhelmed city hospitals and highlighted the absence of any antiviral drugs or vaccines. Almost a decade later, little has changed as the treatment still “focuses on managing your symptoms” and nothing more. If another chikungunya wave were to hit, Delhi’s healthcare system would again be on its knees.

Prevention is the only real defense, which means controlling mosquito breeding. Yet the city struggles mightily on that front. This year’s heavy rains have authorities worried as every waterlogged street or puddle is a potential chikungunya factory. The virus does not spread from person to person in casual contact, so the battle must be fought in the drains, sewers and stagnant pools where mosquitoes multiply.

Unfortunately, Delhi lags in this fight. Mosquito control efforts have been patchy at best. The Municipal Corporation admits it has filled barely half its insecticide-spraying and breeding-checker posts. Residents routinely complain that fogging machines come only after cases explode, not as a preventive measure. It is a tragic irony where lakhs of rupees are spent on fogging chemicals and awareness ads every year, yet basic drainage maintenance is so poor that mosquitoes get royal nurseries in our neighborhoods. With chikungunya having no cure, one would expect the authorities to treat vector control as a life-and-death priority. Instead, we get reactive, band-aid solutions, where the authorities fog the neighborhoods after people fall sick, instead of fixing the broken drains beforehand.

Chikungunya’s long-haul of joint pain is literally “breaking bones”, but Delhi’s broken system seems unable to get ahead of it. The capital’s drainage network, much of it decades-old and silt-choked, is one culprit. In fact, many of Delhi’s major storm drains date back to the colonial era and were designed for a city of the 1970s, which was a mere 60 lakh people; and not the 26 million who live here now. No wonder these antiquated drains overflow even in normal rain.

What’s truly frightening is that despite these known issues, the government’s response has been glacial. Delhi’s new drainage master plan has been stuck “in the works since 2016” with no approval, leaving the city to wade through each monsoon with an obsolete drainage design. The costs of this inaction are paid in human suffering as in each chikungunya victim clutching their swollen joints and wondering why this incurable virus still finds fertile ground in India’s capital city.

Japanese Encephalitis: Inflammation and Fatality

If chikungunya bends bones, Japanese encephalitis (JE) boils the brain. Japanese encephalitis is a highly dangerous viral infection that causes inflammation of the brain (encephalitis). It is spread by mosquitoes (typically the Culex genus) that breed in waterlogged paddies and pools. Though relatively rarer in urban Delhi, JE looms over much of South Asia, including parts of India, especially during monsoons. Experts consider it “Asia’s most common cause of viral neurological disability”, which can be termed as a scourge especially among children. There is no cure for JE. Once the virus invades the brain, it can only be treated with supportive intensive care; vaccination is the only viable way to prevent the disease in high-risk areas.

The symptoms of Japanese encephalitis start deceptively like a flu with high fever, chills, severe headache, nausea, vomiting. But in a subset of patients, the infection progresses with terrifying speed into full-blown brain inflammation. Victims may suffer seizures, lose the ability to speak or move, become confused and agitated, or slip into a semi-conscious coma. The virus effectively short-circuits the central nervous system.

The outcomes are often devastating. According to pathologists, JE kills up to 30% of those who develop the disease (mostly children), and among survivors, half are left with permanent brain damage such as paralysis, recurrent seizures, inability to speak, memory loss, or other cognitive disorders. In other words, only about one-third of JE patients ever return to full health. Little wonder that encephalitis of any kind is considered a life-threatening emergency. Medical authorities warn that once the brain swells, “inflammation can injure the brain, possibly resulting in a coma or death” and that even survivors may face months of recovery or permanent effects.

Delhi’s hospitals fortunately do not see many JE cases, but that offers little comfort as the conditions for an outbreak are increasingly present. The mosquitoes that spread JE thrive in standing water like paddy fields, marshes, and even urban sewage ponds. In 2025’s exceptional monsoon, parts of Delhi and its outskirts have been under water for days at a time, effectively creating new mosquito breeding habitats.

Public health officials are on edge because encephalitis, while rare, has no specific treatment and can overwhelm intensive care units. As one Cleveland Clinic neurologist put it plainly: “Encephalitis can be life-threatening, regardless of the cause, and most people with encephalitis require hospitalization so they can receive intensive treatment, including life support measures.” In severe cases of JE, patients need ventilators to keep them breathing and medications to reduce brain swelling, all just to give them a fighting chance to survive.

Delhi’s authorities have been distressingly slow to bolster defenses against JE and other brain-swelling viruses. A vaccination drive for JE in rural endemic regions of India has saved many young lives, but in urban centers like Delhi the vaccine is not part of routine immunization. The hope is to prevent mosquitoes from breeding and biting in the first place. However, the same civic failures that fuel dengue and chikungunya also leave the door open for JE.

Waterlogging in low-lying neighborhoods, construction sites with rainwater puddles, clogged drains; these ensure that even Culex mosquitoes (which usually prefer dirty water and rice fields) can find a niche in the city. The dire condition of Delhi’s civic infrastructure thus sets the stage for what should be a preventable tragedy. If JE were to flare up in the capital, it would be a catastrophe with a 30% fatality rate and many survivors permanently disabled, even a small cluster of cases could wreak havoc. It is deeply worrying that despite lakhs spent on health programs, the government has not eliminated mosquito breeding on the urban fringes where JE vectors lurk.

The long haul of JE is measured in lives irrevocably altered where a child is surviving encephalitis but never regaining full speech, or a parent coping with post-encephalitic seizures. And yet, Delhi’s preparedness seems limited to issuing standard advisories each year. There is little evidence of coordinated, proactive measures like clearing stagnant water from all construction sites or deploying massive rural-style fogging around wetlands.

When confronted in July 2025, after weeks of heavy rains, a senior Delhi official merely noted that the next two months will be “crucial” in tackling the spread of diseases such as dengue and malaria; JE wasn’t even mentioned by name, perhaps an oversight or a sign of denial. But ignoring the risk won’t make it vanish. Japanese encephalitis stands as a menacing specter over any waterlogged city in its range. Delhi would do well to remember that, and not wait until an outbreak forces a desperate response.

Zika Virus: A Tiny Terror for the Unborn

Among the mosquito-borne threats, Zika virus is infamous for what it does to the most vulnerable, i.e., the unborn. Zika grabbed global headlines in 2015–16 when an epidemic in the Americas led to thousands of babies being born with abnormally small heads (microcephaly) and brain damage because their mothers were infected during pregnancy.

Zika is spread by the same Aedes mosquitoes that carry dengue and chikungunya. It is a stealthy virus as an estimated 80% of infected people have no symptoms at all, and those who do usually experience only mild issues like fever, rash, joint pain, headache, and redness in the eyes. In fact, many people “don’t know they have it” or mistake it for a minor illness. So why is Zika so feared? Because if a pregnant woman catches it, the virus can pass to the fetus and “prevent the fetus’s brain from developing properly,” causing a constellation of severe birth defects.

There is no specific medication or cure for Zika virus disease. For the average healthy adult, this might not seem terrifying. You get some fever and rash, and it goes away in a week. But for pregnant women, Zika is a nightmare scenario. Doctors have to deliver the awful news that nothing can be done to reverse the virus’s damage to the fetus. Microcephaly, the hallmark birth defect from Zika, is lifelong and often accompanied by other serious problems such as vision or hearing loss and seizures. In essence, a single mosquito bite at the wrong time can derail an entire life before it even begins. It’s hard to imagine a more disturbing outcome of a mosquito bite.

Delhi has not reported major Zika outbreaks yet, but small clusters of cases have been detected in India (for instance, in Gujarat and Rajasthan in recent years). The concern is that the Aedes mosquito is rampant in Delhi, and with global travel it would only take one infected traveler to spark local transmission. If dengue is present, Zika could be too as they are spread by the same insect in the same environments. The only saving grace is that Zika so far has not gained a foothold in the capital. But the conditions are ripe: pooled water, inadequate sanitation, and swarms of Aedes mosquitoes buzzing around in the post-rain humidity.

The authorities’ handling of potential Zika threats in Delhi reveals the same pattern of complacency. Zika requires aggressive mosquito control and public education, especially urging pregnant women to avoid mosquito bites. There have been advisories. For example, Delhi’s health department has reminded people that the rainy season “is helpful for mosquitoes of Dengue, Chikungunya, Malaria etc. It is our duty to take care of prevention of mosquitoes breeding”. But on the ground, one sees little urgency.

Take the waterlogging issue. Every pool of water under a broken road or in an open construction pit is basically a nursery for Aedes aegypti. These mosquitoes breed in clean stagnant water like that found in discarded tires, flowerpots, or puddles. Delhi’s drainage failures ensure countless such breeding sites. In July 2025, city inspectors found over 9,100 new mosquito breeding sites in just one week after heavy rains. This coincided with above-normal rainfall and lingering waterlogging; exactly the scenario that could let Zika slip in and spread unnoticed.

Imagine the panic if even a handful of Zika cases were confirmed in Delhi. Public trust in authorities is already shaky after repeated dengue surges, which would likely collapse. In Brazil, the government had to deploy the army in 2016 to go door-to-door eliminating breeding sites during the Zika crisis. Is Delhi prepared for such a drastic measure? Given that our civic bodies struggle to achieve even 50% of their annual drain desilting targets, it is doubtful.

For instance, in 2024 the Delhi government launched a ₹400 crore desilting plan for its key drains, but by the start of monsoon only 16% of the work had been completed, leaving an estimated 115 lakh cubic metres of silt still clogging those drains. This unremoved silt means poor drainage and more standing water, and thus more Aedes mosquitoes free to breed and potentially spread Zika. The chain of official negligence could not be clearer, nor more frightening.

So far, Delhi’s unborn have been spared the horrors of Zika-induced birth defects. But it would be dangerously naive to assume we are immune. With climate change extending monsoon rains and urban flooding, the city is ever more hospitable to tropical diseases once seen as distant. Zika is a tiny virus, but its impact is generational. If the authorities do not strengthen preventive measures, aggressive mosquito control, rigorous antenatal monitoring in case of any hint of an outbreak, and widespread public awareness, a Zika outbreak could truly become Delhi’s darkest nightmare in some future monsoon.

West Nile Virus: The Silent Invader

Another incurable menace carried by mosquitoes is the West Nile virus (WNV). West Nile is a flavivirus (in the same family as dengue and Zika) that originated in Africa but is now found across the world. It is commonly spread by Culex mosquitoes (which often bite at dusk and breed in dirtier water). West Nile virus is particularly insidious because most people (around 80%) show no symptoms at all.

This allows the virus to fly under the radar. About 1/5 infected people develop “West Nile fever,” a flu-like illness with fever, headache, body aches, swollen lymph nodes, and sometimes a rash. These symptoms, while unpleasant, usually resolve within a week. The real danger lies in the rare cases where WNV invades the nervous system. Less than 1% of infections lead to severe neurological disease, but when it does, it is often devastating.

Severe West Nile infection can cause encephalitis or meningitis, which is inflammation of the brain or the membranes around the brain and spinal cord. Patients with neuroinvasive West Nile may experience intense headaches, very high fever (above 103°F/39.5°C), stiff neck, confusion, tremors, seizures, paralysis, and coma. In these cases, the virus essentially attacks the central nervous system, and it can be fatal.

There is no cure for West Nile virus infection, and no vaccine for humans. Treatment is purely supportive with IV fluids, pain control, and ventilators if needed. Some survivors of severe West Nile encephalitis are left with long-term effects like memory loss or muscle weakness. The virus’s name itself carries historical weight as it was first identified in Uganda’s West Nile district, where it was named, back in 1937.

India has not documented large West Nile outbreaks, but sporadic cases have been reported. Given that Culex mosquitoes are abundant (they are the same genus that transmits JE), it’s likely that West Nile virus is circulating quietly at a low level. During monsoons, with stagnant water everywhere, Culex populations can boom. One must consider that if even a handful of those mosquitoes carry WNV, people could be getting infected without knowing it, chalking it up to “viral fever.” Only if someone develops encephalitis would the alarm bells ring, and by then it might be too late for that patient. This is the silent threat of West Nile as its symptomless spread allows it to lurk undetected.

Delhi’s public health surveillance would have a hard time catching West Nile unless they specifically test encephalitis cases for it. It’s not part of routine screening in most hospitals. This adds to the worry, because our city could be blindsided. If ever there were a cluster of unexplained brain inflammation cases, how quickly could our labs identify West Nile?

The past gives little confidence as in multiple emerging disease outbreaks, we have seen delays in diagnosis and confusion. Now consider the backdrop: Delhi’s civic authorities are barely keeping up with known diseases like dengue. Each year thousands of dengue cases are reported (6,391 cases in 2024, and a staggering 9,266 in 2023). When we struggle to contain a familiar foe like dengue, one doubts there is bandwidth to proactively hunt an occult threat like West Nile.

The infrastructure failures aggravating this risk cannot be overstated. When drains overflow and sewage mixes with rainwater, the resulting foul pools in neighborhoods become prime breeding sites for Culex mosquitoes. In Gurugram, citizens pointed out that drains built at high cost have not prevented flooding. For instance, a ₹2 crore drain in Dundahera village failed to stop about a dozen houses from getting submerged in water this monsoon. Across the region, it’s the same story that crores spent on drainage, yet waterlogging persists.

Gurugram’s municipal corporation alone spent a staggering ₹503 crore on the city’s drainage infrastructure over the past nine years, but as one frustrated resident said, “Nothing has changed since 2016” as the city still succumbed to flooding after a heavy rain. Delhi too pours money into de-silting and pumping operations every year, yet key underpasses and colonies go underwater in every big downpour. This is not just wasteful; it directly contributes to health hazards.

When the waters finally recede, they leave behind puddles and muck where mosquitoes breed, and sometimes even floating garbage and carcasses that attract pests. The public outrage is palpable: people are asking where these crores of taxpayer funds went, as they wade through filthy water with mosquitoes buzzing around their faces.

In such an environment, the West Nile virus can quietly propagate. The worrying tone here is not hypothetical. In other countries, West Nile has caused serious outbreaks when conditions align. In the United States, for example, a single wet summer in 2012 led to hundreds of neuroinvasive West Nile cases and dozens of deaths, catching cities off-guard. Delhi must not be complacent simply because West Nile is less well-known locally. The prudent approach would be to drastically improve mosquito control across the board, which, again, loops back to fixing drainage and waterlogging.

Yet on that front, progress is crawling. The PWD Minister in Delhi recently claimed some success in clearing 35 out of 45 chronic waterlogging sites quickly with mission-mode teams. But in the same breath he acknowledged several problem areas that still flood badly, often due to broken or insufficient drains. The truth is that until the systemic issues are resolved, aging drains, encroached drainage channels, poor desilting practices, and lack of coordination, Delhi will remain a petri dish for mosquito-borne infections old and new. And West Nile, the silent invader, will be among them.

Dengue Fever: The Ubiquitous Menace

No discussion of mosquito-driven disease in Delhi is complete without dengue fever, the perennial scourge of the tropics. Dengue is so common in the capital these days that it hardly makes headlines unless an outbreak is severe. But it is exactly this normalization that is dangerous. Dengue is caused by any of four related viruses (DENV-1 through DENV-4), carried by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that thrive in dense urban environments.

Each year, typically between July and November, Delhi sees a spike in dengue cases as these mosquitoes proliferate in the post-monsoon period. Dengue fever usually manifests with sudden extremely high fever (often ~104°F), intense headaches, bone-rattling pains in muscles and joints (it’s nicknamed “breakbone fever” for a reason), pain behind the eyes, nausea, vomiting, and a red rash. These symptoms set in about 4–10 days after the mosquito bite and can last 3–7 days.

For many patients, dengue is miserable but not life-threatening. However, a significant number, about 1/20 by some estimates, progress to severe dengue, also known as dengue hemorrhagic fever. In severe dengue, as the initial fever abates, the patient can suddenly develop dangerous warning signs: severe abdominal pain, frequent vomiting, bleeding gums or nose, blood in vomit or stool, and sudden extreme fatigue or restlessness. This heralds internal bleeding and shock, which is a medical emergency. Severe dengue is a life-threatening condition that can be fatal if not treated in time.

According to experts, it causes a form of haemorrhagic fever where blood vessels leak and organs can fail; without prompt care, patients can succumb to internal bleeding. There is no specific antiviral cure for dengue either as doctors provide supportive care like IV fluids, electrolyte management, blood transfusions if needed, and oxygen support. A vaccine exists but is not widely used due to safety concerns for those not previously infected. For all practical purposes, dengue remains incurable and must be prevented, not cured.

Delhi’s dengue situation is a barometer of the city’s public health performance, and it’s not a flattering one. In 2023, Delhi officially recorded 9,266 dengue cases with 11 deaths, a dramatic rise from 4,469 cases in 2022. Even 2024 saw 6,391 cases, showing that dengue has firmly entrenched itself. And 2025 seems poised to continue the trend: by July 28, the city had 277 cases, the second highest in the last five years for that point in the year (only 2024 had slightly more by that date).

This spike is attributed directly to the heavy rains and waterlogging in July. Delhi received 259.3 mm of rain in July 2025 against a normal of ~210 mm, and the standing water left behind created a bonanza for mosquito breeding. Indeed, in one week of July, over 9,000 new breeding sites were detected and destroyed by MCD teams, and officials noted that the above-average rainfall “likely contributed” to the surge in dengue and malaria cases.

The frustration among citizens is that dengue is a known annual enemy, yet the authorities seem to mount the same ineffective defense each time. There are public awareness drives (“10 minutes every Sunday, check your home for standing water” and so on), there are fines on households for mosquito breeding, there is periodic fogging, and still the numbers rise. Why? Because the fundamental issues of infrastructure are not fixed.

Drains remain clogged with silt and garbage. A survey found many of Delhi’s major drains still choked, posing a clear threat of waterlogging as the monsoon set in. The MCD has claimed progress. For instance, by late July 2025 they said they cleared over 1.93 lakh metric tonnes of silt from drains (about 92.5% of their desilting target).

Yet the floods on the streets suggest even a small fraction of uncleared silt is enough to cause blockages. The problem is exacerbated by fragmented responsibility as multiple agencies in Delhi manage different drains and often work at cross-purposes. Only recently were 22 major drains consolidated under one department to try to solve the coordination problem. But as of the 2024 monsoon, that initiative had a slow start as only ~16% of the planned de-silting of those key drains was accomplished before the rains. The result? Massive waterlogging at underpasses and arterial roads due to drains still choked with an estimated 115 lakh cubic metres of silt. In other words, despite plans and budgets, execution faltered badly.

This systemic failure means dengue will keep exacting its toll. Every monsoon, hospitals fill with dengue patients on drip lines, some struggling as their platelet counts drop and fluids seep out of their blood vessels. The city’s major hospitals like AIIMS, LNJP, GTB, and others brace themselves each year with additional dengue wards and reserved beds. In 2025, the MCD directed several hospitals (Hindu Rao, Swami Dayanand, Kasturba Hospital, etc.) to reserve over 150 beds collectively for mosquito-borne disease patients. That kind of preparation is prudent but also telling that it is an admission that we expect significant outbreaks, as if they are as inevitable as the rains.

And what about the lakhs and crores spent to improve infrastructure and prevention? By official accounts, huge sums have been allocated to upgrade drains and mitigate flooding. Gurugram, as noted, spent over ₹500 crore on drainage since 2016. The Delhi government earmarked ₹400 crore to desilt major drains over 2024–2026. The Union government announced ₹2,517 crore in 2023 to expand water bodies and drainage in urban areas to control floods.

These numbers are staggering and yet each heavy rain seems to render them meaningless. In Gurugram, crucial drainage projects remained unfinished despite crores poured in, leaving spots like the Southern Peripheral Road and Dwarka Expressway as annual waterlogging hotspots due to incomplete works. Residents talk openly of “bureaucratic hurdles, financial mismanagement, and possibly corruption” impeding these projects. It is hard not to be disturbed by the thought that while public money disappears, public health deteriorates.

For dengue specifically, breaking the cycle requires political will and community action on a war footing. Singapore, for instance, managed to reduce dengue for years through rigorous enforcement of anti-breeding rules and smart urban design. In Delhi, laws exist but enforcement is inconsistent.

One week you see domestic breeding checkers issuing hundreds of legal notices; the next week, heavy rains wash silt and trash right back into the very drains that were cleaned, or new construction leaves trenches that fill with water. The system seems broken at every level, from urban planning (where drains and flood zones are afterthoughts) to maintenance (which is reactive rather than preventive) to healthcare (which is stretched to capacity each year by outbreak after outbreak).

The cumulative effect on citizens is a deep sense of worry and anger. With climate change making monsoons more erratic and intense, many Delhi residents fear that each year could be worse than the last as there may be more rain, more flooding, more mosquitoes, and more disease. The term “long haul” is apt; diseases like chikungunya can cause long-term pain, and the city’s fight against these diseases has itself become a long, grinding haul with no end in sight.

What Is The Way Forward: From Disturbing Present to Preventive Future!

Delhi’s current trajectory with incurable mosquito-borne diseases is undeniably disturbing. The combination of broken bones and broken systems has created a public health crisis in slow motion. Chikungunya leaves patients stooped in pain while infrastructure remains stooped in dysfunction. Japanese encephalitis and West Nile lurk as unspoken threats, ready to strike if we continue neglecting the basics. Zika threatens the next generation even before birth. Dengue, the old foe, exploits every crack in our defenses to infect thousands each year. And through it all, the authorities’ response has lagged, characterized by complacency, poor planning, and post-disaster scrambling instead of pre-emptive action.

Yet, it does not have to be this way. The knowledge and tools to address these challenges exist. What Delhi needs is a drastic shift to preventive governance. This means investing in resilient infrastructure, completing drainage projects on time, using modern engineering (as the Indian Road Congress guidelines outline) to ensure roads and drains are built scientifically to channel water away.

It means updating that 1976 drainage master plan to reflect 2025 realities and population loads. It means restoring natural water bodies and floodplains that act as sponges, instead of letting every inch be paved over. It means enforcing building regulations so that new developments include proper storm drainage and rainwater harvesting, rather than just adding to runoff and burdening old drains.

Crucially, it means tackling corruption and apathy that have led to the current mess. When ₹503 crore results in hardly any improvement, there must be accountability. Citizens’ voices, like the Gurgaon residents who decried the “shameless” neglect of duty after multiple officials were transferred and projects left half-done, should be heeded. Public health cannot be held hostage to red tape and graft.

On the health front, a truly preventive approach would drastically scale up mosquito control before the rains hit. Imagine if by May each year, every construction site in Delhi was inspected and cleared of standing water, every drain desilted 100%, and every community marshaled to remove or cover any water-holding trash. Instead of half-measures, the city would mount a full-court press on mosquitoes. The technology even exists for early warning. For example, trapping mosquitoes and testing them for viruses, so we know if West Nile or Zika is present in an area before human cases erupt.

So far, Delhi’s approach has been symptomatic as much like giving paracetamol to a dengue patient and hoping for the best. The symptoms here are waterlogging and disease; the disease is poor governance. Without curing that, the prognosis is grim. Already, climate experts predict heavier downpours and more urban flooding events in coming years. If the system doesn’t improve, we could see a perfect storm: a record flood, followed by a record dengue outbreak, or worse, an emergence of something like Zika or a mutant virus in our midst.

Sounding the alarm is the first step to action. Delhi, and urban India at large, must recognize that public health security is intertwined with infrastructure and the environment. The citizens of Delhi deserve better than to live in fear every monsoon; fear of stepping out into waterlogged streets, fear of a tiny mosquito deciding their fate, fear that the next fever could be something incurable.

The long haul of chikungunya and these other diseases will continue until bold steps are taken. The money has been spent, and more will be, but it must yield results on the ground, like dry homes and streets during rains, fewer mosquitoes, cleaner drains, and stronger healthcare support for those who do fall ill. Until then, Delhi’s monsoons will remain a season of dread, which is a calamitous period when nature’s fury meets human negligence, and the weakest among us pay the price with their health or lives. It is a future we must strive to avert, starting now.