Mulund Tragedy Is Not An Exception. It’s A Pattern India Refuses To Fix.

A metro slab collapse in Mumbai’s Mulund has once again exposed the fragile underbelly of India’s infrastructure sprint. As inquiries and fines follow, a deeper question emerges: are these isolated accidents and for how long will innocent, unsuspecting citizens continue to pay the price?

On Saturday afternoon, a portion of an under-construction pillar of Mumbai Metro Line 4 collapsed onto vehicles on LBS Marg in Mulund West, killing an autorickshaw driver and injuring three others. The incident occurred around 12:20 pm near the Johnson & Johnson and Oberoi premises, when a concrete parapet slab fell from the elevated metro structure during ongoing construction work.

Emergency teams – fire brigade personnel, Mumbai Police, metro officials and 108 ambulance services – rushed to the site. The injured were shifted to nearby hospitals. Traffic was disrupted, panic spread, and within minutes, visuals from the accident began circulating widely on social media.

What intensified public anger was the timing. Just days earlier, a user on X had flagged visible cracks on a metro pillar near Mulund’s LBS Marg and urged authorities to intervene before tragedy struck. The post went viral. The Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) had acknowledged the post at the time and stated that the visuals were misleading and not linked to structural risk. After Saturday’s collapse, MMRDA clarified that the earlier viral images were from a different pier and location, and that the Mulund incident involved a parapet portion, not the cracked pillar shown online.

A high-level inquiry has now been ordered. Construction on the affected stretch has been halted. MMRDA imposed a fine of ₹5 crore on the contractor and ₹1 crore on the general consultant. Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis described the incident as unfortunate and said strict action would follow if lapses were found. Local political leaders visited the site, met the injured, and assured residents that accountability would be fixed.

But the larger question lingers: is this merely an isolated construction accident or a symptom of something deeper?

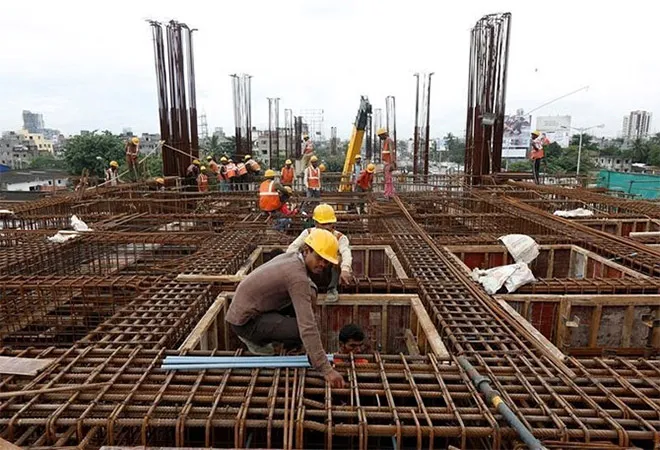

India’s Infrastructure Sprint

Over the past decade, the government has aggressively expanded capital expenditure, positioning infrastructure as the backbone of economic growth. Annual capital outlay in recent Union Budgets has crossed ₹10 trillion, with infrastructure development accounting for more than 3% of GDP. A 2023 analysis by Crisil projected that India’s cumulative infrastructure spending between 2023-24 and 2029-30 could reach ₹143 trillion – more than double the previous seven-year period.

Airports, expressways, metro networks, railway corridors, freight terminals, bridges and highways have been built at record pace. The ambition – transform logistics, reduce bottlenecks, attract manufacturing, and project India as a global growth engine.

Speed has become a central feature of governance. Deadlines are tight. Announcements are frequent. Projects are fast-tracked. But speed without supervision is a risk multiplier.

A Pattern That Refuses to Disappear

Mulund is not an isolated episode.

According to data from the National Crime Records Bureau, 1,630 structures collapsed in 2021 and 1,644 in 2022 — the latest year for which comprehensive records are available. A 2020 research paper by the Central Road Research Institute found that between 1971 and 2017, over 2,100 bridges in India collapsed either during construction or before completing their design life.

Recent years have seen airport canopies cave in during heavy rainfall, newly constructed bridges collapse within months of inauguration, expressways develop structural damage soon after opening, and urban flooding overwhelm freshly built roads.

These failures occur not decades after commissioning, but often alarmingly soon after completion – sometimes even during construction. The issue is no longer whether India can build fast. It is whether it can build safely.

Norms Exist. Enforcement Does Not.

India does not suffer from a shortage of rulebooks.

The National Building Code of India 2016 lays down detailed standards. The Indian Roads Congress prescribes comprehensive technical guidelines. There are established Indian standards for construction materials and structural safety. In many cases, these standards are aligned with global norms.

The problem is not the absence of engineering frameworks. The problem is adherence. When structures collapse prematurely, the failure is rarely because there were no guidelines. It is because oversight mechanisms failed to ensure compliance.

In case after case, inquiries identify lapses in execution, supervision, or quality control – not the absence of codes. Hence, norms are not the problem. Enforcement is.

The L1 Procurement Trap

A structural flaw lies at the heart of public infrastructure procurement: the dominance of the L1 model – awarding contracts to the lowest bidder.

In theory, this ensures cost efficiency. In practice, it often incentivises aggressive underbidding. Contractors operating on razor-thin margins may then attempt to recover profitability by cutting corners — on materials, on supervision, on safety protocols.

Layered onto this is a public procurement ecosystem where corruption allegations are not uncommon. When bids are driven primarily by cost rather than technical robustness or track record, quality risks multiply.

The system structurally rewards winning cheaply, not building durably.

Unless procurement models evolve to prioritise lifecycle cost, safety compliance and technical evaluation, tragedies will continue to emerge as periodic shocks rather than systemic wake-up calls.

Design and Oversight Gaps

Beyond procurement, there are deeper institutional weaknesses.

Government departments awarding large infrastructure contracts do not always possess adequate in-house technical expertise to evaluate complex designs thoroughly. Independent third-party audits are not consistently embedded at every stage – from design vetting to material certification to real-time execution monitoring.

Site supervision can be fragmented. Preventive inspections are often less rigorous than post-disaster investigations.

A reactive governance model dominates: action intensifies after collapse, then fades as headlines recede.

In Mulund, questions are already being asked about whether traffic movement below the structure should have been temporarily restricted during installation of the parapet section. Such site-level precautions are basic safety considerations in elevated construction.

If these are overlooked, the problem is not merely technical. It is managerial.

The Familiar Script After Every Collapse

Public infrastructure disasters in India tend to follow a predictable script.

- An accident occurs.

- A life is lost.

- An inquiry is announced.

- A contractor is fined or blacklisted.

- Junior officials may face suspension or transfer.

- Statements of regret are issued.

Then, gradually, the system resets.

Blacklisting often proves ineffective, as new entities emerge under different names. Administrative penalties rarely travel upward in the hierarchy. Political accountability remains diffuse. Structural reforms in procurement or oversight are seldom sustained with urgency once public attention shifts.

This cyclical response breeds institutional complacency.

When consequences are limited and accountability rarely reaches decision-making levels, deterrence weakens.

The Real Crisis: Accountability

India’s infrastructure drive is economically justified. Roads, metros, bridges and airports are essential for long-term growth. Large-scale capital expenditure can stimulate demand, reduce logistics costs and strengthen manufacturing competitiveness.

But infrastructure is not merely about pouring concrete. It is about governance.

- It is about inspection regimes that function.

- It is about engineers empowered to halt work if standards slip.

- It is about procurement systems that do not prioritise price over safety.

- It is about transparent audits and real-time monitoring.

- It is about consequences that are credible.

When a slab falls in Mulund after a viral warning about cracks circulates online, even if technically unrelated, public trust erodes. Citizens begin to question whether early warnings are acted upon seriously. They question whether oversight is proactive or performative.

An infrastructure model that prioritises rapid commissioning without equally strengthening accountability mechanisms creates structural risk.

The Last Bit, Back to Mulund

In Mulund, a man lost his life. Three others were injured. A fine has been imposed. An inquiry has been ordered. Safety audits have been promised.

These are necessary steps.

But unless the accountability framework travels beyond contractors to the broader architecture of decision-making and oversight, similar headlines will recur – in another city, on another project, under another agency.

India’s infrastructure ambition is undeniable. The question is whether the governance model supporting it is evolving at the same speed. Because without accountability embedded into every layer of the system, the race to build faster may continue but the cracks will widen.