Did NIRF 2025 Ranking Blunder Exposed Indian Education System’s Low Rank In Providing Quality Education?

India’s National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF), the country’s flagship college ranking system has been hit by an embarrassing controversy. In the 2025 NIRF rankings, Banaras Hindu University’s Faculty of Dental Sciences managed to appear twice on the list of top dental colleges, at two different ranks. This bizarre double listing, with conflicting data for the same college, has raised alarm about the accuracy and integrity of India’s higher education rankings. It’s not just a one-off glitch; observers say it’s symptomatic of deeper problems plaguing the Indian education system.

A Dental College Ranked Twice: Inside the BHU Mix-up in NIRF 2025

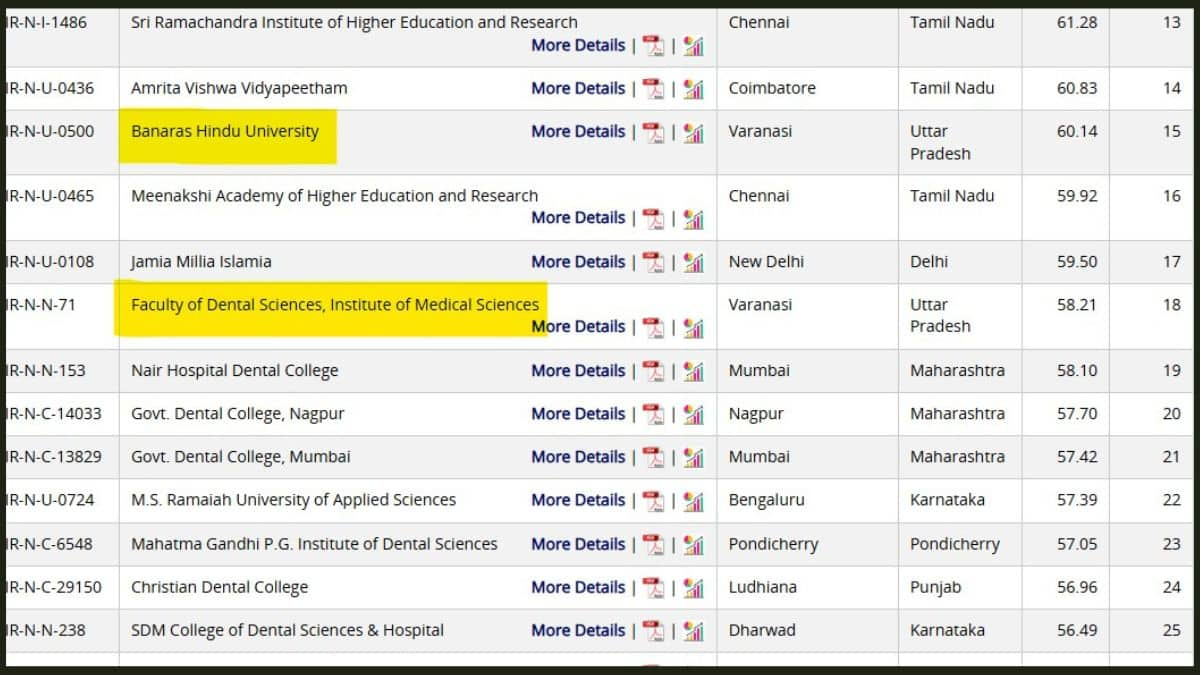

When the NIRF 2025 rankings were released (after a delay in early September), students and academics scouring the lists noticed something odd in the “Dental Colleges” category. Banaras Hindu University (BHU), one of India’s most prestigious institutions, seemed to have two entries for what appeared to be the very same college;

Rank 15: “Banaras Hindu University” (Faculty of Dental Sciences)

Rank 18: “Faculty of Dental Sciences, Institute of Medical Sciences, BHU”

Both entries referred to BHU’s dental college, yet each was listed with a different rank and score. At face value, it looked like BHU had two separate dental institutions in the top 20, which it doesn’t. This first-of-its-kind anomaly immediately cast doubt on the NIRF’s data verification process.

How could the same college be ranked twice? According to BHU insiders, the root cause was a duplication in data submission. Prof. Harakh Chand Baranwal, Dean and Head of BHU’s Dental Faculty, admitted that the college submitted its data directly to NIRF, and the central university administration also submitted data “at the last minute,” leading NIRF to treat them as two entries. Essentially, a miscommunication or overlap between the department and university resulted in two separate dossiers of data for the same institution.

The NIRF system, apparently lacking a safeguard to catch duplicate entries, went ahead and ranked both submissions as if they were different colleges. Even more troubling, the two entries did not have identical data or scores, suggesting some inconsistencies crept in, such as:

Conflicting placement figures: One submission (likely from the faculty) reported that 20 undergraduate students were placed in jobs in 2021-22, whereas the other (from the central admin) claimed zero students placed that year. For 2022-23, one listed 23 UG placements vs. 20 in the other.

Different salary outcomes: The median salary for graduates also diverged. For example, for 2021-22 the faculty’s report showed a median UG salary of ₹14 lakh, whereas the university’s report showed none (since it claimed no placements). Even in 2022-23, the two entries had median salaries of ₹12 lakh vs. ₹9.6 lakh.

Score discrepancies: Because of these data differences, the scores that NIRF assigned on various parameters varied widely between the two entries.

Notably, the perception score (a measure of reputation) differed by over 17 points (63.77 vs. 46.48) for what is ostensibly the same college. It’s baffling that the “Faculty of Dental Sciences, IMS, BHU” could have a much lower reputation score than “BHU”, highlighting potential flaws in how NIRF’s survey captured the name versus the institution.

Such inconsistencies are more than clerical errors; they directly affect how the college is viewed by prospective students. “Placements and salary outcomes are key decision-making factors when choosing a college,” notes an education expert, and conflicting numbers in a national ranking can severely shake the confidence of students and parents. Indeed, many Indian families treat the NIRF rankings as a trusted guide for college admissions, akin to a quality stamp. Now, with BHU’s case, students are left second-guessing that if even a top university’s data can appear contradictory, how reliable are these rankings?

NIRF Under Scrutiny: Verification Gaps and Methodology Issues

The BHU incident has prompted calls for an urgent review of NIRF’s methodology and verification process. It turns out this controversy couldn’t have come at a worse time for NIRF, which was already under scrutiny in 2025 for data integrity issues. In fact, the release of the NIRF 2025 rankings was delayed by several months due to a legal challenge in the Madras High Court.

Back in March 2025, a public interest litigation (PIL) filed by C. Chellamuthu of Tamil Nadu accused NIRF of being fundamentally flawed. The PIL alleged that NIRF relies solely on unverified data submitted by institutions, with no independent audit or fact-checking. This, the petitioner argued, had led to widespread manipulation that colleges are inflating figures to climb up the ranks. The Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court found the concerns serious enough to impose an interim stay on the release of the 2025 rankings in late March. As the court noted, if ranking scores are based on potentially false data, the entire exercise could mislead students and “harm the country’s higher education system”.

During the hearings, evidence was presented comparing some universities’ NIRF submissions with their official reports to the National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC). The findings were damning. In many cases, the numbers in the NIRF data were significantly higher than those in the NAAC-validated reports including more PhD scholars, more faculty, bigger research funds, etc. Given that NAAC involves on-site inspections and expert validation, whereas NIRF had no such verification, the implication was clear that some institutions were juicing their stats for NIRF. The petitioner pointed out that reputable public universities were often outranked or excluded while certain colleges “with subpar infrastructure and quality” managed to secure top ranks, likely by gaming the system.

The High Court’s intervention forced the Ministry of Education and NIRF’s administering body (the National Board of Accreditation) to pause and respond. By April 2025, as the case progressed, there was intense national debate on how India measures educational quality. The court effectively froze the rankings until it was satisfied with the process. (A final hearing was slated for April 24, 2025.) Though the PIL was eventually dismissed later in the year, it had already exposed major cracks in the ranking framework.

What changed for NIRF 2025? Facing scrutiny, the Ministry of Education introduced a few new measures aimed at shoring up credibility.

Negative marking for research fraud: For the first time, NIRF 2025 instituted a penalty for institutions that had research papers retracted due to fraud or plagiarism. Under the “Research and Professional Practices” metric, if a university’s papers are withdrawn from journals, it loses points. Initially the penalties are mild, serving as a warning, with promises of stricter enforcement in future editions. This was in response to criticism that universities were publishing prolifically without quality control, sometimes even in dubious journals, which is nothing but a “publish or perish” culture that led to junk research just to score points. –

Additional categories and parameters: NIRF 2025 introduced a new category on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to evaluate institutions on societal and environmental impact. This broadened the assessment beyond pure academics, possibly to discourage a narrow focus on research quantity. Also, self-citations (where colleges cite their own papers to boost counts) were removed from consideration in research metrics, and other tweaks were made to reduce gaming.

Tighter rules (in principle): The Education Ministry claimed it had put stricter rules and “additional evaluation parameters” in place for 2025. However, the true test is in implementation and as the BHU episode showed, even basic data deduplication might have slipped through.

Despite these changes, the medical college category in NIRF 2025 was almost dropped entirely due to data integrity concerns. There were rumors in August 2025 that NIRF would omit ranking medical colleges that year because of “persistent data discrepancies” in that field. (Medical institutes had been under a cloud after some were caught misreporting data in earlier years.) In the end, NIRF did publish a medical colleges ranking for 2025, with AIIMS Delhi at 1, but only after additional scrutiny. The very consideration of skipping a whole category underscores how widespread the data problem is. This shows that if you can’t trust the numbers colleges report, you can’t honestly rank them.

The BHU dental college fiasco further cements the impression that NIRF’s verification is lax. In Prof. Baranwal’s words, an internal inquiry is now looking at “how such conflicting entries slipped through NIRF’s verification mechanisms”. Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan, who unveiled the rankings, has not publicly addressed the BHU mix-up yet. But education experts are blunt. In other words, the credibility of NIRF, painstakingly built since 2016, is at stake.

Gaming the Rankings: An Open Secret

Those in academia often quip that “university rankings are a game, and everyone’s playing it.” The NIRF ranking scandal is shining a light on just how that game is played in India. A cottage industry of consultants and strategists has sprung up in recent years, all promising colleges help in improving their NIRF scores (often in ethically dubious ways). With government funding, student admissions, and prestige tied to rankings, the temptation to fudge the numbers has grown.

According to one estimate, over 10,000 institutions participated in NIRF 2024, and consultants typically charged ₹3–5 lakh per institution to boost their ranking metrics. That implies a ₹400-500 crore “ranking improvement” industry operating in the shadows. What do these consultants do? Insiders and whistleblowers reveal a menu of data manipulation tactics:

Inflating faculty count: Some colleges list guest lecturers and adjunct faculty as full-time faculty in their NIRF data. Since NIRF values a low student–faculty ratio and a high proportion of PhD-qualified teachers, padding the faculty roster (even temporarily during the data collection period) is a common trick. There have been instances of institutes hiring faculty on paper or borrowing faculty from sister institutions just to meet the NIRF deadline.

Exaggerating research output and funding: NIRF’s research score (RPC) counts publications and research income. To game this, colleges have been known to split one research grant across multiple departments (counting it multiple times) and report higher total funding. Likewise, a culture of “publication inflation” exists, where faculty is pressured to crank out papers in bulk.

A 2020 audit found a substantial number of Indian research papers in predatory journals, arguably a direct result of institutions chasing NIRF points for publication count. In extreme cases, there have been “authorship marketplaces” where one can literally buy a co-authorship on a research paper for a fee, just to pad resumes and NIRF data. This commodification of research undermines academic integrity. “When scholarship is reduced to a transaction, the foundation of academic credibility is shaken”.

Phantom students and placements: Graduation Outcomes (GO) is another key metric. It looks at how many students graduate on time, how many get jobs or go on to higher studies, and what their median salaries are. Here too, institutions can mislead. There have been cases of inflating placement numbers and salaries without proper documentation.

One consultant described a scenario where a university client fretted their patent count was too low compared to a rival; the consultant coolly replied: “Just make it 100… If NIRF checks, which they don’t, we’ll buy some patents. I’ll arrange it.”. This illustrates the brazenness where data is treated as malleable since audits are unlikely. As a result, some lesser-known colleges have reported surprisingly high placement salaries or near-100% placements, raising eyebrows among recruiters.

Manipulating perception surveys: NIRF includes a “peer perception” component, which is a reputational survey among academics and employers. While harder to directly fake, there have been reports of institutions lobbying their networks to rate them highly, or even attempts to flood the survey with positive responses. The weight of perception (10% in many categories) has been criticized as unduly subjective and biased towards older, well-known institutions. Yet paradoxically, new colleges try to game it by aggressive branding and even ad campaigns touting their (perhaps inflated) accomplishments to sway opinions.

All of this has happened largely because NIRF operated on an honor system. “Institutions upload their data. No audit. No validation. No consequences, until now,” wrote education columnist Dr. Deepessh Divakaran, describing the ranking framework as a “house of cards built on spreadsheets.” Unlike NAAC accreditation, where teams physically verify documents and campus facilities, NIRF historically trusted colleges to be truthful. That trust, many argue, was naïve. “This system, designed with noble intent, has mutated into a mechanism that rewards manipulation over merit,” Dr. Divakaran lamented.

The results of these games are evident in some ranking outcomes. The Policy Circle reports an example where a college in Karnataka soared in the NIRF 2024 rankings despite glaring inconsistencies between its NIRF data and its NAAC-audited data. Educationists had flagged the case as suspicious as the college’s meteoric rise did not align with any known improvement on the ground, suggesting that creative data reporting was at play.

It’s also telling that no institution has ever been penalized for misreporting data to NIRF so far. In theory, submitting false information is grounds for disqualification, but enforcement has been absent. The Madras High Court’s stay on NIRF 2025 was the first real comeuppance for this trend, and it has forced authorities to consider verification seriously.

Students and honest academics have been the collateral damage of rank fraud. When rankings turn into a numbers game, colleges feel incentivized to “teach to the ranking”, focusing on metrics that boost scores rather than genuine educational quality. For instance, a university may invest in churning out numerous low-impact research papers (because NIRF counts them) instead of improving teaching methods or mentorship (which NIRF doesn’t directly measure). “We need mentors, not paper-pushers chasing metrics. What message are we sending when dubious research is rewarded over genuine student engagement?”. The obsession with rankings reduces education to “a numbers game, driven more by manipulation than improvement”.

For students, a fraudulent ranking can lead to heartbreak. Consider a student who chooses a college because it was ranked, say, in the NIRF top 50, only to graduate and find the education sub-par and the degree not valued by employers. There are real human costs. A recent exposé found dozens of institutions falsely claiming accreditations or rankings, which led students to enroll under false impressions. In one case, a family spent ₹10–15 lakh on an MBA at a B-school that trumpeted a European accreditation status, only to later find it was merely a membership, not a full accreditation.

Graduates from that program struggled to get jobs at top firms, and felt cheated. In another instance, a university in Uttar Pradesh advertised a NAAC “A+” grade while it actually had a much lower B grade, duping students until media investigations exposed the truth. The University Grants Commission eventually named and shamed over 50 such institutions in 2024 for making false claims about rankings or accreditation. But by then, the damage to student trust was done.

Accreditation Scandals: When Quality Assurance Is Compromised

Parallel to the ranking shenanigans, India’s system for accrediting colleges, which is meant to assure quality, has had its own credibility crisis. The National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC), which gives colleges and universities quality grades (like A++, A+, etc.), was rocked by a corruption scandal in recent years. In early 2023, a Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) probe alleged that some NAAC peer reviewers (evaluators) were accepting bribes from institutions in exchange for high grades. One high-profile case involved Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation (KLEF), a deemed university in Andhra Pradesh. CBI investigations suggested that during a NAAC inspection visit, assessors solicited a ₹1.00–1.80 crore bribe to ensure KLEF received the top grade.

The fallout was swift and significant. By February 2025, NAAC’s leadership undertook a drastic purge, removing nearly 900 peer assessors from its roster amid concerns about compromised evaluations. This was almost 1/5th of all accredited assessors, an enormous churn aimed at cleansing the system. An internal review found that some evaluators had insufficient data or suspicious patterns in their past assessment reports, while others had direct complaints against them. NAAC’s director, Ganesan Kannabiran, was quoted emphasizing that “integrity is not a line item, it is the very foundation of trust in the system”. He sent letters to every remaining assessor underscoring that their work is a “nationally important assignment,” not a mere formality.

In addition to firing tainted assessors, NAAC overhauled its evaluation process:

For colleges, NAAC stopped physical campus visits entirely. Instead, assessments would be done in an online mode, to eliminate the chances of hospitality and bribery influencing scores. (Under the old system, there were reports of some colleges wining and dining NAAC teams, even offering lavish gifts or “hospitality” packages to sway them. NAAC’s new guidelines explicitly warn institutions and assessors to avoid any such “elaborate” treatment and report undue inducements.)

For universities, NAAC moved to a hybrid model, mostly remote evaluation with a few targeted on-site checks for verification. This selective approach aims to catch irregularities while reducing opportunities for cozying up to inspectors. NAAC also indicated a shift toward greater data analytics and comparison. For instance, if an institution challenged its grade and sought re-evaluation, NAAC would compare the reports from different teams. In some cases, they discovered large discrepancies, suggesting one of the teams had been overly lenient or compromised, leading to those evaluators being blacklisted.

Despite these reforms, the damage to NAAC’s reputation was considerable. Accreditation, which is supposed to be a rigorous vetting of academic standards, had been reduced to something some colleges felt they could buy. Indeed, the larger theme emerging is that Indian higher education is struggling with accountability on multiple fronts. If rankings can be gamed and accreditations can be bought (or faked), the entire signaling system that students and stakeholders rely on becomes meaningless. “Fake accreditations and flawed rankings damage the future of students as well as India’s global standing in education.”

It’s telling that only 22 Indian business schools have obtained the esteemed AACSB international accreditation as of 2025 (a very rigorous process). For the vast majority, NAAC and NBA (National Board of Accreditation) are the benchmarks, and those need to be above reproach. The NAAC scandal and NIRF controversies have prompted the Union Education Ministry to consider a major revamp of the quality assurance framework.

There are talks of replacing NAAC’s system with a “NAAC 2.0” that relies more on data and less on human discretion, and even of merging multiple regulators into a new Higher Education Commission (as envisaged by the National Education Policy 2020). But policy changes are slow; in the meantime, students and parents are navigating a minefield of potentially misleading claims.

Voices of Concern As Students, Educators Demand Accountability

The ongoing controversies have elicited strong reactions from across the academic community, from students and faculty to policy experts. Students feel betrayed. Many students preparing for college admissions or competitive exams say their faith in the system is eroding. “Our time, money, and crucial years of preparation are being wasted. Who is answerable for that?” lamented one aspirant after repeated glitches in a government recruitment exam. This sentiment resonates in the college rankings context too. “We relied on these rankings to choose a good college,” says Radhika, an MBA student, “but now I wonder if some colleges just faked their way to a higher rank.” The trust deficit is real.

On social media, hashtags like #NIRFIntegrity and #ReformEducation have popped up alongside trending tags such as #SSCMisManagement that highlight exam fiascos. It’s as if students are collectively saying that please give us a system we can trust. Academics and experts are calling for transparency. Education experts argue that NIRF and accreditation agencies must be far more open about their processes. For instance, NIRF could publish the raw data of all institutions and highlight anomalies. “NIRF should publish exactly how it tallies retractions and give institutions a way to appeal,” wrote one commentator, noting that clarity in methodology would build trust.

A director of a private university (who asked not to be named) shared: “Each year we wait for NIRF like it’s an entrance exam result. There is pressure from the top management to improve our rank. Yes, we hired a consultant. Yes, we worked backwards from the criteria. But we never lied on data, that line we won’t cross.” His words illustrate the fine line many walk that delves around optimizing for the ranking versus outright falsification.

The BHU dental dean’s frank admission of a mistake is rare, more often, institutions go quiet when caught in a controversy. In this case, BHU at least initiated an inquiry. “That call on removing one of the duplicate entries NIRF will have to take as it is not in our hand,” Prof. Baranwal said, subtly suggesting that the ranking body should correct the record.

Even some government voices have hinted at concerns. The Vice-Chairman of the Tamil Nadu State Council for Higher Education, in a column, questioned “whether a ranking system modeled on global frameworks is relevant in the Indian context.” He noted NIRF’s bias toward research output and elitism, pointing out that it often overlooks colleges that do great work in uplifting underprivileged or first-generation learners, because such colleges might not excel in publishable research or fancy infrastructure.

This is an important perspective as a pure quantitative ranking might inadvertently sideline the very institutions that are doing the heavy lifting of social inclusion and teaching-focused education. “The obsession with global-type rankings,” he argued, “can reduce our institutions to chasing metrics rather than fulfilling their core mission”.

Broader Implications Are “Is India’s Education System at a Crossroads?”

Zooming out, these episodes, the NIRF ranking duplications and data fudging, the NAAC bribery scandal, frequent exam paper leaks and procedural failures, are all symptoms of a larger malaise. India’s education system, from school to university to professional training, is often criticized for being compromised by systemic issues.

Regulation vs. capacity: India has seen an explosion of new colleges and universities in the past two decades. Regulating quality at over 1,000 universities and 40,000+ colleges is a Herculean task. Oversight bodies (NAAC, NBA, UGC, etc.) have struggled with capacity and perhaps vigilance. When oversight is lax, unscrupulous practices find space. The rise of “deemed-to-be universities” and private institutions, some of which operate as businesses first and educational institutions second, adds pressure on regulators to ensure standards aren’t diluted in the profit chase.

High stakes exams and their pitfalls: The fixation on entrance exams and government job exams in India means any flaw in those processes triggers outrage. In the past few years, paper leaks and technical glitches have plagued exams from the school level (board exam leaks) to medical and engineering entrances, to recruitment tests. For example, the NEET (medical entrance) paper leak in 2023 led to arrests and an ED (Enforcement Directorate) investigation, and the 2024 NEET-UG saw an alleged scam involving impersonators and leaked answer keys.

The Staff Selection Commission (SSC) exam protests in 2025 (where students faced center cancellations and even reported being met with police batons when protesting) illustrate how mistrust is boiling over. In one protest, a student angrily noted, “The government awarded the tender to a blacklisted company. How can a company with such a background be trusted with exams that determine our future?”. That plea echoes the sentiment around colleges that “How can we trust institutions that are caught misrepresenting themselves?”

Policy and implementation gaps: The Indian government has not been idle. The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 lays out an ambitious roadmap to reform both school and higher education, emphasizing critical thinking over rote learning, holistic multidisciplinary colleges, a new regulator (the Higher Education Commission of India) for transparency, and an overhauled accreditation approach. However, policy is only as good as its execution. The controversies suggest a lag between intent and reality. While NEP talks of “light but tight” regulation (meaning fewer forms of regulation but stricter enforcement where it exists), we are seeing either “light but loose” (rankings with no checks) or “tight but porous” (accreditation with corruption) scenarios.

Public vs private tensions: Some observers point out that many data manipulation allegations involve private institutions eager to make a mark, whereas venerable public institutions (the IITs, IIMs, central universities) have reputations that don’t depend on NIRF as much. This isn’t a private=bad, public=good binary; there are excellent private universities and underperforming public ones, but it does raise the question of how to create a culture of integrity across the board. If government funding or approvals are linked to rankings (which they increasingly are; for instance, a good NIRF rank can be a prerequisite for some grants or the Institution of Eminence tag), then the government itself has a stake in ensuring those ranks mean something real.

At stake is not just the fairness of a list or the bragging rights of colleges, but the future of millions of students and India’s global educational reputation. As one policy analyst put it, “India has the world’s largest youth population. If we fail to equip them with the right skills and mindset, it would be a missed opportunity”. Right now, too many graduates are leaving college with degrees that employers question.

A 2023 study by Aspiring Minds (an employability assessment firm) found that over 40% of Indian MBA graduates were underemployed, many working in jobs that didn’t require a postgraduate degree. Part of the reason, analysts suggest, is the “glut of dubious credentials”, when every other new private college is “Top Ranked” or “Internationally Accredited” on paper, it’s hard for recruiters to trust any of it. In the long run, if Indian institutions gain a reputation abroad for exaggerated claims, it could hurt opportunities for tie-ups and for graduates wanting to study or work overseas.

At The End, Restoring Trust and Moving Forward Is What We Demand…

The twin tales of a dental college listed twice and a court stepping in to halt rankings have served as a wake-up call. They reveal that India’s higher education system, while brimming with potential, has been undermined by a race for rankings and approvals at any cost. This is a moment of reckoning, but also an opportunity to set things right.

As the dust settles on the NIRF 2025 controversy, one hopes it leads to a stronger, cleaner framework in 2026 and beyond. Trust, once broken, is hard to rebuild, but not impossible. India’s education system stands at a crossroads. It can either continue on the path of chasing ranks at any cost, or turn the corner towards authentic quality and accountability. The choice made now will profoundly shape the nation’s future, because the education of its youth is nothing less than the education of its destiny.