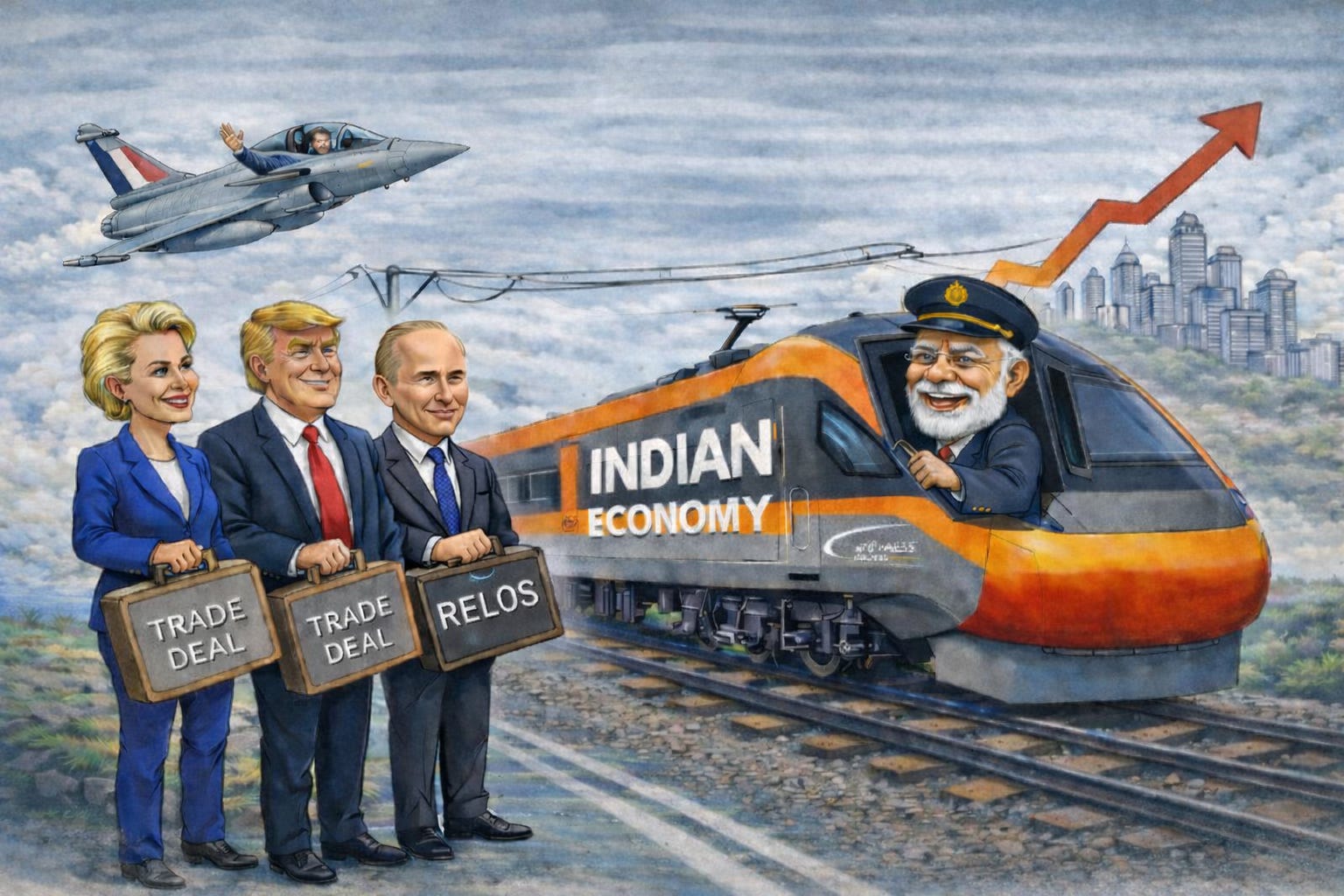

The $500 Billion India–US Trade Deal: Has India Truly Gained? Access Restored, Autonomy Tested

When the United States and India unveiled their interim trade framework, the headline number dominated the conversation: American tariffs on Indian goods, which had climbed to a punitive 50%, would now fall to 18%. For exporters battered over the past months, the relief was immediate. Markets responded positively. The rupee steadied. Industrial lobbies breathed easier.

But beneath the celebrations lies a far more complex and uncomfortable reality.

This is not a conventional trade agreement between two sovereign equals recalibrating tariffs for mutual gain. It is a conditional restoration of market access – one tied explicitly to geopolitical alignment, energy sourcing decisions, and ongoing compliance monitoring by Washington.

The 25% punitive duty linked to India’s purchases of Russian oil was rescinded only after U.S. President Donald Trump issued an executive order stating that India had “committed to stop directly or indirectly importing Russian Federation oil.” Simultaneously, the U.S. Commerce Secretary was tasked with monitoring India’s compliance, with authority to recommend reinstatement of tariffs if India “resumes” oil imports from Russia.

That is not free trade. That is conditional access. To an older generation of Indians, the structure feels eerily familiar. In 1991, India turned to the International Monetary Fund during a balance-of-payments crisis. Access to capital came with conditions – reforms, restructuring, oversight. The difference then was necessity. The difference now is agency.

In 1991, India negotiated with a multilateral institution to survive an economic emergency. In 2026, India appears to have accepted bilateral monitoring in exchange for tariff relief, where the framework restores access. But it also introduces leverage that now sits firmly in Washington’s hands.

The question, therefore, is not whether tariffs fell from 50% to 18%.

The question is: at what structural cost?

The Tariff Reset – Relief, But With Strings Attached

At first glance, the reduction of U.S. tariffs on Indian goods from 50% to 18% appears decisive, offering long-awaited relief to exporters hit by months of punitive levies. But the significance lies not in the number, but in the conditions attached to it.

The earlier escalation (a 25% reciprocal tariff followed by an additional 25% levy tied to India’s purchases of Russian crude) had pushed duties to nearly 50%. The rollback now removes the oil-linked component, yet only conditionally. President Donald Trump’s executive order frames the relief around India’s commitment to curb Russian imports and authorises monitoring with the possibility of reinstating tariffs if imports resume. In effect, market access has been restored but tethered to compliance.

Market Access

Alongside tariff recalibration, India has granted selective access to its domestic market.

Industrial equipment, certain computer-related products, and advanced medical devices will now enter at reduced or zero duties. Data-centre hardware (critical for India’s expanding AI ambitions) has also received concessions. While this aligns with India’s digital growth strategy, it also deepens reliance on U.S. technology supply chains.

In agriculture, the openings are more politically sensitive. Distillers Dried Grains with Solubles (DDGS), soybean oil, selected fruits, tree nuts, and certain wines and spirits will receive tariff concessions.

The government has emphasised that core staples – rice, wheat, maize, millets – remain protected. Genetically modified crops will not be allowed. Dairy, poultry, meat and ethanol sectors have been insulated.

The calibration appears deliberate. Yet interim agreements often set precedents that shape future rounds of negotiation.

Export Gains

On the export front, India has secured zero-duty or preferential access for key sectors including generic pharmaceuticals, gems and diamonds, smartphones, and certain aircraft components.

Labour-intensive industries are expected to regain competitiveness in the U.S. market, potentially stabilising employment and export volumes.

However, significant exclusions remain. Section 232 tariffs – imposed under U.S. national security provisions – continue to apply to steel, aluminium, copper, and segments of the automobile industry. These sectors, which account for billions in exports, will still face duties ranging between 20% and 50%.

Thus, the relief is meaningful but not universal.

The $500 Billion Commitment

The most consequential aspect of the framework is India’s stated intention to purchase approximately $500 billion worth of American goods over five years.

Energy products, defence hardware, aircraft, advanced technology, chips and servers, coking coal, precious metals – the scale spans nearly every strategic sector.

To contextualise: total bilateral trade between the two countries in 2025 stood around $130 billion. U.S. exports to India were approximately $42–45 billion. A $500 billion commitment over five years implies a near doubling of annual imports from the United States.

This is not incremental trade balancing. It is structural reorientation. The economic arithmetic of such a commitment warrants deeper scrutiny, particularly for a country already running a substantial trade deficit.

Energy Realignment

Energy flows have already begun shifting.

Russian crude (once accounting for nearly 40% of India’s oil imports) has fallen sharply. Imports from the United States have risen significantly. Indian Oil Corporation has diversified procurement toward West African and Middle Eastern grades.

Officially, these adjustments reflect market logic and evolving price dynamics. Unofficially, the timing aligns closely with Washington’s tariff rollback. Whether commercial recalibration or diplomatic compliance drove this pivot may remain debated. What is indisputable is that energy behaviour now intersects directly with trade access.

Regulatory Alignment

Beyond tariffs and purchase commitments, the framework also envisages cooperation on non-tariff barriers – standards alignment, medical device regulations, digital trade protocols, and conformity procedures.

Such clauses appear technical. Yet regulatory harmonisation can gradually reshape domestic policy space, influencing how industries evolve and how sovereignty is exercised in practice. Taken together, the interim framework restores access, opens markets selectively, and commits India to significant import expansion – all within a compliance-sensitive architecture.

On the surface, it is pragmatic. But once we examine the monitoring mechanism and the snapback provision, the deeper nature of the arrangement becomes harder to ignore.

Trade Deal – Conditional Access, Not Contractual Certainty

A traditional trade agreement rests on reciprocity. Tariffs are reduced in exchange for market access, quotas are negotiated, and dispute resolution mechanisms are institutionalised. Once signed, businesses operate with predictability.

The interim framework between India and the United States departs from that logic.

The rescinding of the 25% punitive tariff linked to Russian oil purchases is not permanent relief. It is suspended enforcement. The executive order explicitly authorises American officials to monitor India’s energy imports and recommend reimposition if India is deemed non-compliant.

That transforms the character of the arrangement.

Indian exporters are no longer operating under a fixed tariff regime; they are operating under a conditional regime. Market access now depends not only on trade performance but on geopolitical alignment.

This is the first structural shift.

The Snapback Clause

The snapback mechanism embedded in the oil-linked tariff is the most consequential element of the framework.

Under its terms:

- The United States retains unilateral authority to assess India’s compliance.

- The 25% duty can be reinstated if India “resumes” direct or indirect imports of Russian crude.

There is no multilateral adjudication process governing that determination. In effect, one party holds discretionary leverage over the tariff environment of the other.

Contrast this with Southeast Asian arrangements, where specific consignments suspected of rule violations are targeted. If a Vietnamese exporter is found to be rerouting Chinese goods, that exporter or shipment is penalised.

In India’s case, the monitoring structure potentially applies to the entire trade relationship. For Indian exporters, this architecture introduces a new layer of risk.

If tariff relief depends on India’s aggregate energy behaviour, firms in textiles, jewellery, or engineering goods may face compliance demands unrelated to their own supply chains. American buyers (particularly large retail chains) may seek contractual protections against sudden tariff reversals.

Affidavits, supply-chain tracing declarations, snapback clauses in contracts, and pricing contingencies could become standard practice. Operational uncertainty raises costs even when tariffs are lower. An 18% rate that may revert to 43% overnight is not the same as a guaranteed 18%.

This is where the IMF analogy begins to crystallise.

)

Trade Deficit Expansion – The Math Problem

If India were to import an additional $100 billion annually from the United States without a proportional expansion in exports, the trade deficit arithmetic changes materially.

Assume no immediate export surge.

India’s existing trade deficit (already substantial) would widen significantly. Even if part of the $500 billion reflects substitution (replacing imports from other countries with U.S. suppliers), concentration risk increases.

Furthermore, defence purchases and energy imports are capital-intensive outflows. They do not immediately generate offsetting export earnings. Technology and semiconductor imports may build capacity over time, but the balance sheet impact is immediate.

An additional $100 billion annually requires either:

- A dramatic export acceleration,

- A compression of imports from other countries, or

- A widening deficit.

Each option carries consequences.

Concentration Risk – From Diversification to Dependency

For decades, India’s external economic strategy has rested on diversification. Energy from Russia, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and the United States. Defence equipment from multiple suppliers. Trade agreements with ASEAN, Europe and beyond.

A commitment that potentially channels over half of incremental imports toward a single country introduces concentration risk. In an era where trade policy is increasingly weaponised, concentration reduces strategic flexibility.

The past year alone has demonstrated how tariffs can be deployed to advance geopolitical objectives. If a future disagreement emerges – on technology standards, digital taxation, defence offsets or regional politics – dependence limits negotiating space.

Energy Substitution

Energy constitutes a major portion of the proposed expansion.

Indian imports of Russian crude surged after 2022 because discounts were steep and commercially rational. At their peak, Russian supplies accounted for nearly 40% of India’s oil imports. More recently, those imports have declined sharply – partly due to narrowing discounts and partly due to tightening sanctions enforcement.

The interim framework accelerates this pivot.

Substituting discounted Russian crude with U.S. energy may align diplomatically, but it also alters pricing dynamics. Even modest differences in per-barrel costs translate into billions annually when scaled to India’s consumption levels.

Energy is not merely a geopolitical variable. It is a fiscal one. If procurement shifts are driven primarily by external pressure rather than commercial calculus, the cost is borne domestically – either through higher subsidy burdens or elevated retail prices.

Defence and Technology

A substantial share of the $500 billion commitment is expected to flow into defence hardware and advanced technology.

On the surface, such purchases enhance capability. Aircraft systems, defence platforms, semiconductor equipment and AI infrastructure can strengthen India’s technological base.

However, capital-intensive imports do not automatically translate into domestic value creation. Unless accompanied by meaningful technology transfer, domestic manufacturing integration and supply-chain localisation, large-scale procurement risks deepening dependency rather than reducing it.

The tension between “Buy American” and “Make in India” becomes acute here.

If high-value defence and tech contracts increasingly anchor production and research within the United States, India may gain equipment but lose ecosystem depth. Long-term industrial policy hinges not just on what is purchased — but where value accrues.

Fiscal Implications

India’s total expenditure in Budget 2026–27 stands slightly above ₹53 lakh crore. A $500 billion import commitment over five years (roughly ₹45 lakh crore at current exchange rates) approaches the scale of an entire annual Union Budget.

While the imports will be distributed across public and private actors, the fiscal ripple effects are real:

- Higher defence allocations

- Greater energy procurement exposure

- Potential pressure on the current account

Unless export growth accelerates dramatically, financing such scale may require increased borrowing or capital inflows. The markets may celebrate tariff relief today. But structural deficits are not solved by sentiment.

The Illusion of Balance

Supporters argue that the $500 billion commitment will reduce the U.S. trade deficit with India, thereby stabilising bilateral relations. That may be true. But bilateral balance does not guarantee national balance.

If India reduces surplus with the United States by increasing imports without expanding total exports, the deficit does not vanish – it shifts.

The question is not whether Washington’s numbers improve. The question is whether India’s external stability strengthens or strains. The arithmetic of this framework reveals something deeper: tariff relief has been exchanged for import expansion. That exchange may buy short-term stabilitym but likelynot preserve long-term autonomy.

Agriculture, The Domestic Fault Line

Few sectors in India are as politically sensitive as agriculture. It sustains nearly half the population directly or indirectly, shapes electoral outcomes across large states, and has repeatedly demonstrated its capacity for organised mobilisation.

The interim framework acknowledges this sensitivity. The government has publicly asserted that core staples (rice, wheat, maize, millets) remain insulated. Dairy, poultry, meat and ethanol have been excluded. Genetically modified food crops are not permitted entry.

Yet the agreement does open the door selectively.

Distillers Dried Grains with Solubles (DDGS), soybean oil, tree nuts, certain fruits, wines and spirits have received tariff concessions. These categories may appear marginal relative to staples, but their cumulative impact cannot be dismissed.

Trade liberalisation in agriculture rarely begins with staples. It begins with derivatives, feed products, edible oils, and processed categories, gradually altering price signals across supply chains.

The Subsidy Asymmetry

The more fundamental issue lies in structural asymmetry.

The United States subsidises its agricultural sector heavily – estimates for 2025 place direct and indirect support north of $40 billion annually. These subsidies enable American producers to export at price levels often below full market cost.

India, by contrast, relies on a politically delicate Minimum Support Price (MSP) system and input subsidies to protect small and marginal farmers. The system is already fiscally strained and administratively contested.

Opening segments of the agricultural market to subsidised imports risks compressing domestic price realisation – particularly in oilseeds and feed categories where margins are thin.

Soybean oil provides a telling example. India already imports substantial volumes of edible oils, including palm oil from Indonesia and Malaysia. Increased concessional imports from the United States could further weigh on domestic oilseed cultivation – undermining long-standing efforts toward self-sufficiency. The concern is not immediate collapse. It is gradual erosion.

The Political Memory of Farm Protests

India’s recent history is indicative how sensitive agricultural reform can be.

The farm law protests of 2020–21 demonstrated the organisational strength of farmer unions and the political cost of perceived market exposure without adequate safeguards. Even when reforms are economically rational, if they are perceived as favouring large corporations or foreign interests, resistance intensifies.

Any expansion of agricultural imports under a U.S. framework will inevitably be interpreted through that lens.

India withdrew from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations in 2019, citing concerns over protecting farmers, dairy producers and MSMEs from import surges.

That withdrawal was framed as a defence of domestic producers against subsidised competition (particularly from China and Australia) The interim U.S. framework raises a natural question: what has changed?

If India could step away from a multilateral Asian trade pact to safeguard agriculture, why accept selective openings under a bilateral arrangement with the United States?

The government may argue that the scale and calibration differ. That may be accurate in technical terms. But politically, the contrast will be noted.

The United States views expanded agricultural access as a win for its rural economy. Statements from American officials emphasise lifting farm prices and reducing the U.S. agricultural trade deficit with India.

From Washington’s perspective, this is rational policy. From New Delhi’s perspective, the optics are delicate. India’s rural electorate has historically wielded disproportionate influence relative to its share in GDP. Even modest disruptions to price stability can trigger wider unrest.

The interim framework may be economically manageable in its current form. But agriculture is not governed by spreadsheets alone. It is governed by perception, trust, and political memory.

The Geopolitical Reorientation

At the most immediate level, the interim framework de-escalates a troubled phase in U.S.–India relations.

Over the past year, tariff escalation had strained ties between two countries that describe each other as “strategic partners.” The reduction from 50% to 18% lowers temperature, restores predictability for exporters, and signals that neither side is willing to let economic friction derail broader cooperation.

For Washington, India remains a pivotal counterweight to China in the Indo-Pacific. For New Delhi, the United States is its largest export market, a major technology partner, and an increasingly important defence supplier.

In that narrow sense, the framework consolidates alignment.

But alignment comes in degrees.

The China Variable

Much of the strategic logic underpinning U.S.–India cooperation rests on shared concern over China’s rise.

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, involving the United States, India, Japan and Australia, has gained renewed emphasis. Defence exercises have expanded. Technology collaboration has intensified.

The trade framework strengthens that axis indirectly by encouraging energy diversification away from Russia and deeper technological integration with the United States.

However, a closer U.S.–India embrace also narrows India’s room to manoeuvre.

India has historically practised multi-alignment – engaging Washington, Moscow, Brussels and even Beijing where necessary. The strength of that strategy lay in flexibility.

If trade access becomes tied to geopolitical alignment, flexibility compresses.

In an era of intensifying U.S.–China rivalry, India’s greatest asset is its autonomy. The more dependent trade flows become on a single relationship, the harder that autonomy is to exercise.

Russia. Quiet Repercussions

Russia has long been a key defence partner and energy supplier for India. Even after the Cold War, military hardware, spares and technology transfer formed the backbone of bilateral ties.

The surge in Russian crude imports after 2022 was not ideological; it was commercial. Discounted oil supported domestic price stability and fiscal management.

The interim framework accelerates India’s drift away from that energy dependence. While Russian imports had already begun declining due to pricing and sanctions pressures, the explicit linkage between oil sourcing and tariff access alters the political context.

Moscow will read the signal. A sustained pivot could prompt Russia to deepen its reliance on China or recalibrate defence cooperation terms. That may not rupture ties, but it alters equilibrium within the broader BRICS grouping.

The BRICS and Global South Optics

India has positioned itself as a leading voice of the Global South – advocating reform of multilateral institutions, promoting south-south cooperation, and emphasising sovereignty in global governance.

Developing economies observe how major powers negotiate with each other. If India – often portrayed as a champion of strategic autonomy – appears to accept conditional trade access linked to geopolitical behaviour, it may alter perceptions of its independence.

The United States, Transactional Statecraft

The framework also reflects a broader shift in American statecraft under President Trump.

Trade is no longer treated as a standalone economic instrument. It is a lever – deployed to advance security, energy, and foreign policy objectives. Tariffs are used not merely to protect industries, but to influence behaviour.

In this context, India is not unique. Allies and competitors alike have experienced similar transactional pressure. The difference lies in scale and precedent.

The interim framework undoubtedly strengthens U.S.–India economic ties in the short term. It prevents industrial disruption and stabilises a strategically important partnership.

But it also tightens the bilateral axis at a moment when India’s long-term strength lies in diversified engagement – with Europe, ASEAN, Africa, West Asia, and even calibrated engagement with China.

Democratic Process and Transparency

One of the more striking features of the interim framework was not its content, but its communication.

The announcement emerged first through social media posts and executive statements, while Parliament was in session. Details of the agreement filtered through press briefings, foreign executive orders, and interpretative commentary — rather than a structured parliamentary presentation.

Trade agreements are not routine administrative decisions. They shape fiscal flows, influence sectoral viability, and intersect with foreign policy. Historically, such frameworks have been debated, scrutinised, and contextualised before the legislature — even when Parliament does not formally ratify them.

The absence of detailed parliamentary briefing creates informational asymmetry.

The Last Bit,

The question is not whether engagement with Washington is desirable. It is whether engagement is evolving into concentration.

India’s historical strength has lain in diversification – of energy sources, defence partners, trading blocs and diplomatic relationships. Strategic autonomy was never isolation; it was flexibility.

The 1991 reforms were born of crisis and tied to structural transformation. Conditionality then was accompanied by a reform dividend. The present framework emerges not from collapse, but from pressure. Its dividend is stability. Its cost is potential narrowing.

If India can leverage expanded imports into domestic capacity – localise defence production, deepen semiconductor ecosystems, convert energy procurement into technological partnership – the long-term gains may justify the present alignment.

If, however, import expansion widens deficits, concentrates dependency and conditions access on geopolitical compliance, the arithmetic and precedent may prove constraining.

India today stands at no precipice. It faces no IMF queue, no emergency airlifting of gold. It negotiates from strength, not desperation.

Which makes the central question sharper: Is this framework a calibrated recalibration within a multipolar strategy or the early architecture of strategic compression?

Access has been restored. Autonomy has been tested but history will decide which mattered more.