Whose Fault Is It Anyway? Is The Government Shrinking Their Responsibility In Handling Cybercrime?

In this frenetic digital age, even the simplest transaction can leave your life exposed to predatory thieves. Data is looted everywhere, sometimes at the local xerox shop, sometimes through your smartphone, and the unsuspecting citizen often pays the price. Imagine walking into a tiny photocopy shop to get your Aadhaar card or some legal papers scanned, then learning later that a criminal has stolen your identity and wrecked your credit.

Tragically, such scenarios are all too real in India today. Researchers have warned that ordinary print-and-copy outlets handle “sensitive documents, including government IDs, legal papers, and confidential records,” often without adequate safeguards. Yet while India’s copy centers buzz away all day long, data privacy and accountability remain window-dressing at best. No advanced encryption protects that stack of papers beside the Xerox machine, and no audit trail tracks where each printout really goes.

Consider the Coimbatore revenue department’s sting operation in June 2020. A local photocopy shop near the tahsildar’s office was caught printing fake district e-passes for travellers. The shop simply took a legitimate pass and manually altered the personal details, but the crucial QR code didn’t match any official record. When police scanned the code, the fraud was instantly exposed. The owner was arrested, but only after a desperate man had been detained trying to travel with the forged pass. This isn’t an isolated comic-book caper, but it’s routine life in India. A casual photocopy of your Aadhaar or passport can end up in the wrong hands, and the fallout is nightmarish.

On the surface, such printing scams seem quaint, but they feed a rising tide of identity theft. Tech analysts report that con artists have actually commercialized this tactic. Hundreds of online “print-on-demand” services advertise government ID printing and laminating, but many are outright frauds. They lure customers with official-sounding promises, then collect personal data and one-time passwords under false pretenses. In effect, the victim unknowingly hands over a digital skeleton key, which is an authenticated identity.

Cloud security researchers trace these rings across states (one major network operates in western Uttar Pradesh), which impersonate well-known firms like India Post or Fino Payments Bank to sow trust. By harvesting OTPs, the scammers gain “escalated privilege” as they can mimic your accounts, apply for loans, or siphon funds with impunity. It’s a vicious feedback loop as more people avoid bankrupt print shops, they flock to unfamiliar online services, and criminal syndicates jump in to exploit the confusion.

The harm is not just abstract or financial, but there is real human drama behind each data breach. Take the case of retired bank manager Ashok, a Pune grandpa who got an alarming midnight call from someone claiming to be a Mumbai Police “encounter specialist.” The caller told him his bank account and Aadhaar were implicated in a money-laundering case. Ashok was terrified; criminals, he was warned, were watching him. For three days, fraudsters kept his phone camera on and guarded him remotely, ordering him not to speak to anyone. Cornered, he handed over details of his life savings. In the end, Ashok lost Rs 1.19 crore, and collapsed in shock, he never recovered.

His story echoes many others. A 82-year-old man lost his life (and savings) trying to clear his name from an invented crime. Elsewhere, a 90-year-old man was tricked out of over one crore rupees by fraudsters posing as Central Bureau of Investigation agents.

In Bengaluru, a 57-year-old was psychologically terrorized for six months, watching her own CCTV feed as criminals impersonated DHL, CBI and RBI officials, until she reluctantly emptied Rs 31.83 crore in bank after bank just to prove her innocence. These victims were law-abiding, ordinary people; as Maharashtra police noted, even well-educated citizens and officers are falling prey to these sophisticated scams.

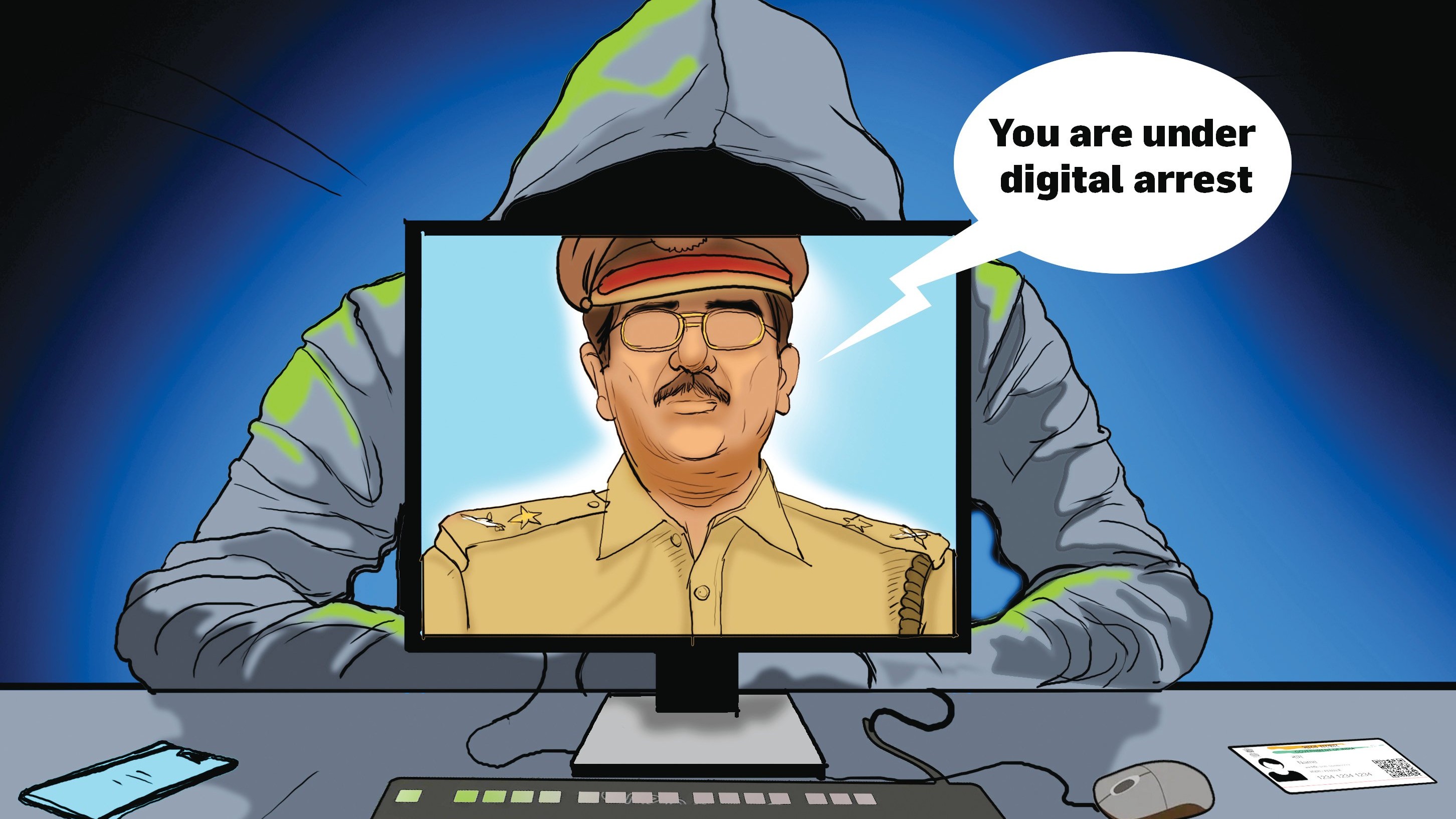

What makes the “digital arrest” scam so devastating is the combination of fear and impersonation. Victims are told, in a stern voice, that they are suspected of drug trafficking or terrorism. They are usually kept on call with someone posing as an officer, with fake uniforms and ID cards flashed on camera, often in a setting mimicking a police interrogation room.

The fraudster insists the victim is under digital custody and threatens imminent jail. Desperate, victims comply with instructions to transfer money under the guise of “proof of funds” or legal fees. CERT-In, India’s computer emergency response team, put it bluntly in October 2024: crooks masquerading as investigators “exploit people by stealing money and private data”. Importantly, CERT-In reminds us that no legitimate agency uses WhatsApp or Skype for real investigations, but that warning often comes too late. By the time a rational thought returns, thousands of rupees have vanished.

The government has not been silent on these issues. In fact, it has launched a barrage of awareness initiatives like newspaper ads, radio bulletins, social media campaigns, even a special Mann Ki Baat segment to alert citizens about digital arrest scams. The Telecom Department began airing a “cybercrime awareness” caller tune repeatedly (8–10 times a day) on all mobile phones, for several months. DoT and the Home Ministry’s Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C) claim to track down these fraud networks: by late 2024 they reported blocking over 7.8 lakh SIM cards and 2,08,469 device IMEIs linked to scams. They even devised systems to block incoming spoofed calls from abroad that mimic Indian numbers.

Yet in spite of all this noise, scammers continue to rake in crores. The sheer scale of losses suggests many doubts about these “victories.” Awareness tunes and prime-time broadcasts can only do so much when the average citizen’s defenses are so thin. The fraudsters have money and patience; the well-intended public service announcements have a shelf life of a day.

In practice, millions of unsuspecting people still answer those belligerent calls. In October 2025, by the way, the Supreme Court had to remind government: digital arrests have no legal basis. Officials emphasize that “anyone can be duped”, citing those human-interest stories of shock and loss, and they urge victims to report quickly. But for many, reporting feels too late, and justice too slow.

Meanwhile, another theme has emerged: it seems like the government shifting the blame onto citizens themselves. Notice the tone of the latest Department of Telecom advisory: citizens are repeatedly warned to beware of tampered devices and fraudulent SIMs.

The government’s ministry states flatly that if a SIM issued in your name is misused, you may be held liable for any crimes committed with it.

The advisory explicitly warns against “procuring SIM cards through fake documents, fraud, or impersonation” and “transferring or giving their SIM cards to others who misuse them”. If your grandson borrows grandpa’s phone and commits fraud, the original owner may find himself at the end of a criminal case, as the DoT says, “the original user may also be held liable as an offender” in such scenarios.

This is a remarkable reversal. The message is: “If someone steals your SIM or uses it with your identity, you are the offender.” One can sympathize with officials, after all, SIM cards are meant to be tied to real people, but the policy feels Kafkaesque for ordinary citizens. An elderly man may not even realize a thief has cloned his SIM. Yet under current rules, he must prove his innocence rather than have the state track down the actual culprit. It’s as if traffic police fined the car’s registered owner whenever someone else crashed it. The government essentially says as if guard your phone better than your home or bank accounts.

Worse, the DoT simultaneously tells us not to use apps that can “modify the Calling Line Identity” (CLI) or other network identifiers. That means no fakery of your own phone number when you call others. The implicit logic could be, if you’re offering tools that might help criminals spoof numbers, avoid them. But here we ask- why such apps are not banned yet? They remain freely downloadable on Android and iOS app stores. The government only advises caution, rather than outright prohibition.

So rogue apps propagate widely (often under benign names like “fake call maker”). This is akin to warning people not to drink bleach, without removing bleach from the supermarket. The secretary of telecom says that citizens should just decide not to use these number-spoofer apps, while in the same breath they leave them on the marketplace. Isn’t this a classic case of putting the burden on the public by saying “Don’t use dangerous things,” rather than actually stopping those things!

From a citizen’s perspective, this is maddening. If the government truly knows these caller-ID modifiers are harmful tools in the wrong hands, why are they not blocked or at least flagged? Why must an citizen, who is a user play tech detective, sifting through app descriptions to figure out which could be lethal? The current approach is half-hearted. It’s as if police posted flyers warning of robberies, but left the bank doors unlocked. Meanwhile, a common man must live in fear that if their own number’s identity is faked, how could they possibly trace or prevent the misuse in time?

To add insult to injury, technology meant to protect us is moving at a glacial pace. Take the Sanchar Saathi portal, the government’s flagship telecom safety platform. It is supposed to allow any citizen to verify all SIMs issued in their name, check device IMEIs, block stolen phones, etc. The telecom secretary calls it an “AI-powered” game-changer, and boasts that over 6 lakh lost phones have been recovered through Sanchar Saathi’s “block my stolen phone” feature. In theory, every Indian can log in, type in a number, and see precisely which SIMs and devices are active in their name, which is a safeguard against unauthorized usage.

Yet in practice, the portal barely keeps pace with a snail. Try this at home: a fresh install, good-speed Wi-Fi, reputable browser, and brace yourself. Each query is like waiting for a grass to grow. Fifteen seconds? A minute? More. By the time Sanchar Saathi finally loads your data, your cup of tea has gone cold. Any elderly user, already anxious to confirm their phone’s status, might think they’ve been abandoned in a workshop vacuum. Meanwhile, the scammer next door is probably using half that time to double-charge your bank account.

This chronic sluggishness is no accident of nature. It stems from outdated infrastructure and perhaps misplaced incentives. We ask, who was awarded the contract to build Sanchar Saathi? If tens or hundreds of crores of public money went into this portal, where did it disappear? Government procurement often hides tangled webs of middlemen and commission. Every delay or bug in these “citizen services” raises suspicions of bureaucratic inertia, or worse, kickbacks from shoddy vendors. After all, one man’s bloated software project is another’s golden opportunity. The citizen just sees an hourglass symbol, the lobby boy sipping chai.

Think of the irony. The government warns you about fast-moving cyber threats, yet its own “weapon” (Sanchar Saathi) can barely turn on. The slogan “Digital India” rings hollow when our portals are lethargic and opaque. Time is money for ordinary folk. Who compensates a daily wage earner for the minutes wasted waiting for a login? And more cynically, if taxpayer funds are meant to fuel e-services, why have they produced a system slower than many private apps? One begins to wonder if the value was ever on speed, or mostly on lining pockets.

In practical terms, the inadequacy of Sanchar Saathi hurts exactly the people who can least afford it. Imagine you are an elderly farmer who suspects your SIM is misused. You log onto Sanchar Saathi to check, but the site spins endlessly, as if it may as well have a “gone fishing” notice. After waiting and failing, you give up. Meanwhile, fraud continues on someone else’s dime. If a scammer cloned your number tomorrow, you might never know until the police knock on your door. At that point, the only evidence you have is the lagging memory of a failed web request.

The government’s own data undercuts its complaint-driven stance. On one hand, they block millions of dubious SIMs every year. On the other, they admit citizens are still getting scammed by relatives or hired hands using their SIMs, which the government insists is the owner’s fault. This contradiction screams policy misalignment. In a logical world, the state would clamp down on all avenues of fraud. It can arrest the criminals, wipe out the rogue apps, shore up security at copy shops, and fund lightning-fast verification tools. Instead, it often amounts to cat-and-mouse games that leave citizens running bewildered.

Nor is the reality much improved by education campaigns. The government’s big play is this mantra: “Stop, think, and verify”. It’s the same advice for romance scammers and loan sharks. To an extent it’s sound as “yes, everyone should question unexpected claims of arrest or lottery”. But telling a frightened grandfather in rural India to “calm down and check a government site” isn’t empathy, it’s blaming the victim. By the time he has any presence of mind, the money is gone. Our cybercrime coordination cell’s motto should perhaps be: “Awareness is great, but arrests are better.”

The disconnect between talk and action leaves citizens outraged. Why, many wonder, can a crafty youngster still download “Call ID Faker 2025” from the play store, spoof numbers with impunity, and ruin someone’s life with a few taps, when the telecom minister knows full well what’s happening? If these apps are illegal, why isn’t the state yanking them offline, or suing their developers?

Why are senior citizens told “don’t use them” as if that magically makes them vanish? And what of compensation? If a SIM is fraudulently obtained, shouldn’t the nation’s telecommunications network (which had increased it’s tariff rates) or at least the party that issued it without verification, share the burden? Right now, the poster child seems to be the citizen’s own irate face, watching helplessly as the law shrugs and says- “You should have been more careful.”

As for Sanchar Saathi, it remains a hallowed idea with shaky execution. It was trumpeted that the portal has helped over 6 lakh victims recover stolen phones, as if flashing a victory badge. But ask an actual user and you’ll hear only one number: fifteen thousand (milliseconds) between request and stall, which feels like an eternity.

A portal’s success isn’t just measured in bureaucracy’s bulletins but in user trust. If the flagship system is sluggish and buggy, why should a common man trust a government warning about suspicious calls? The epistemic dissonance of preach vigilance, but make your own tools vexing, erodes faith in all official advice.

In the end, India’s cyber-safety battleground is littered with contradictions. We are told identity theft is a priority, yet a xerox shop can shred your life and walk free. We are told to beware of digital arrests, yet conmen keep calling. We are threatened with prison for SIM fraud, yet see no help in blocking stolen numbers swiftly. Every scam reported paints a damning picture of gaps in enforcement: crowded market squares where pickpockets run free.

The one thing that remains certain is this, that the blame falls unevenly. Criminals and shady businesses run rings around enforcement, and the common man, especially the vulnerable and the elderly, endures the fallout. Over the din of government assurances, you can almost hear their urgent question echo: Who will take responsibility for all this? For now, the answers and the fixes remain as elusive as a blacked-out caller ID.