Chor Ke Ghar Se Chori, That’s Indian PoliceGiri: How Seized Hawala Cash Vanishes In Uniformed Pockets!

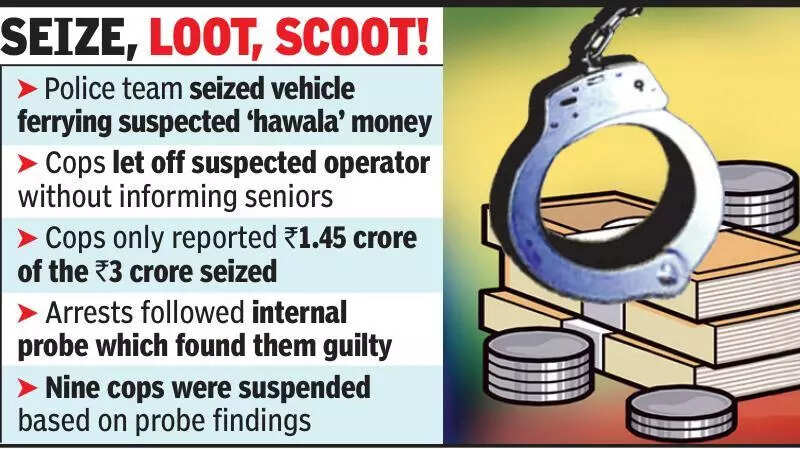

In mid-October 2025, a major corruption scandal exploded in Madhya Pradesh. Police in Seoni had intercepted a car carrying ₹3 crore in hawala cash, allegedly bound for Maharashtra. But instead of logging the entire haul, the story goes, the officers “transferred the cash into their own vehicles” and reported only ₹1.45 crore the next morning. Chief Minister Mohan Yadav quickly ordered a probe, and within days eleven officers were booked and six arrested.

Media reports detail a sordid “50-50” deal where the police supposedly planned to keep ₹1.5 crore and return the rest, until the hawala operator discovered ₹25.6 lakh missing from the returned sum.

The case even spurred a habeas corpus petition when the complainant’s wife alleged her husband was illegally detained by police to suppress the truth. As one anguished official put it, “when the protectors of law become its destroyers, such betrayal will not be tolerated”. In other words, the thieves were robbed.

Is this an aberration or the norm? In India’s long history, the answer depressingly leans toward the latter. Similar stories have surfaced across states in recent years, painting a grim picture of cops flaunting the law rather than enforcing it. For example, just a year earlier in Mumbai a Government Railway Police inspector was caught red-handed demanding a ₹10 lakh bribe to go easy on an extortion case. The Anti-Corruption Bureau (ACB) nabbed him via a lawyer’s wallet and ₹4.5 lakh was seized en route to the officer’s pocket.

Commentators noted that “GRP has been under a cloud of corruption” with police using fake baggage checks to shake down passengers. In Punjab, an Assistant Sub-Inspector ran an extortion network in cahoots with overseas gangsters, collecting ₹83 lakh in cash and even buying himself a Toyota Fortuner with the loot. The SSP explained that the ASI’s American-based sons helped funnel protection money to him, illustrating how deep the rot can run.

Far from isolated, corruption in the police has been rising. Delhi Police data show criminal cases against officers nearly doubled from 15 in 2022 to 29 in 2023. Disturbingly, the types of crimes include extortion, fraud and custodial abuse. The NCRB report confirms this. In 2023 Delhi recorded 19 corruption cases (a 72% jump over 2022), mostly misconduct and bribery.

But convictions lag woefully as only 5 officers were ever convicted despite 16 arrests. The upshot is that bribe-taking, even of money meant for government coffers, has become alarmingly common. India’s police seem to have invented a “fanciful 50-50 banking system” during seizures; keep half and remit the rest, evidently an accepted practice rather than a dereliction.

Other recent scandals underline the trend. In Chandigarh, two police sub-inspectors were arrested by the CBI for demanding ₹5 lakh in a GST case; a full ₹2.5 lakh of it captured on video as they pocketed bribe. Nationwide, even the offices of bureaucrats and enforcement agencies have become synonymous with graft. Chennai-based freight firm Wintrack last month abruptly shut down India operations, publicly citing “harassment and bribery demands” from customs officials. In fact, the company’s founder named customs officers on social media, alleging ₹50,000 payoffs were taken to clear shipments.

The fallout was immediate as Congress MP Shashi Tharoor branded the episode “truly dismaying,” noting that corruption is “rampant” and that businesses often pay bribes as the “price of doing business” in India. Infosys veteran Mohandas Pai echoed the outrage, scolding the government: “You have failed to stamp out systemic corruption in our ports… we need a bribe-free, hassle-free system.”. The customs saga even reached Parliament, highlighting how extortion by enforcement (police, customs, regulators) has undermined faith in India’s business environment.

This endless string of exposes has tarnished the image of law enforcement and governance. Transparency International ranks India 96th out of 180 countries on the 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index (score 38/100), reflecting widespread perception of official venality. India also tops the charts for actual bribery rate in Asia (39%), with 89% of citizens saying corruption is a “big problem”. The World Justice Project’s 2024 Rule of Law Index ranks India 79th of 142 countries, specifically calling out our “very low score in the absence of corruption”. (By contrast Singapore, ranked 3rd globally, scores near-perfect on anti-corruption and enforcement.)

In India’s latest index results, the absence of corruption dimension placed us 97th out of 142, reflecting the sub-par policing and chronic graft underscored by cases like the Seoni hawala heist and Wintrack affair. A World Justice Project chart on the Rule of Law Index dramatically illustrates India’s slide into low rankings on corruption and enforcement, whih is a sign of glaring weakness.

The economic implications are dire. Corruption isn’t just a moral outrage; it “takes away potential resources” and hobbles growth. Studies estimate bribery drains more than 5% of global GDP. Every rupee funneled into corrupt pockets is a rupee not invested in schools, roads or industry. Specifically for developing economies like ours, research shows that rising corruption sharply cuts growth. A 1% rise in corruption is associated with about a 0.7 percentage point drop in GDP growth. For India, this is material as we’ve seen how payroll expenditures under the NREGA have been gutted by graft (one study found 79% of funds vanished in on-site bribes).

Big businesses know this, and some are voting with their feet. The Wintrack shutdown is just the latest symbol of an “ease of doing business” facade masking on-the-ground hassles. Despite official claims of better business reforms, entrepreneurs complain of endless clearances and “arbitrary enforcement.” In the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index 2023, India ranked 38th of 139 countries (improving), but still lags behind China (19th) and many peers.

Many firms recount horror stories: an exporter told media that without paying bribes, “your consignment can sit indefinitely… If you protest, they’ll delay it further.” Shashi Tharoor’s phrase, that bribes are now the “price of doing business”, is echoed by countless frustrated traders and even public finance officials. As one industry leader grimly tweeted during the Wintrack saga, “Bribery is the only ease of doing business in India.”

It goes without saying that a weakened rule-of-law and rampant graft erode investor confidence. Surveys (from TI’s Global Corruption Barometer to local chambers) regularly find 60–70% of firms admitting to paying bribes just to get routine work done. India’s CPI decline over the past year (-1 point in 2024) and our stagnant business rankings reflect precisely these institutional failures. A formal CII report notes that despite removing many regulations on paper, India still saddles businesses with 1,536 Acts and 69,233 compliance conditions; corruption and delay are what foreign investors really face.

In short, the “chorgiri” we’re talking about is not victims robbing thieves, but our own police and officials robbing us. It taints every honest cop who silently obeys the law, and undermines public trust. It also shrinks the tax base (stolen hawala money never sees Treasury, and bribes reduce government revenue). For the economy, corrupt cops and babus are a double-whammy as they extort businesses, spook investors, and divert funds that could have built infrastructure or jobs.

The recent exit of Wintrack is a stark warning: if a humble cargo firm can be pushed out, what of our higher ambitions for growth? Without systemic reform, full transparency in seizures and prosecutions for errant officers, such scandals will keep recurring. As MP CM Yadav vowed, “Those found guilty… will face strict legal action.” One can only hope the promise is kept, else India will keep losing not only crooks’ money, but also its reputation and economic momentum.