The Rot Within: How Sassoon Hospital Became A Breeding Ground For Corruption, Negligence, And Injustice Over 25 Years

When Healing Becomes a Business, and Dying Becomes Profitable: How Sassoon Hospital Became a Monument to India's Institutional Decay

Walk through the corridors of Sassoon General Hospital in Pune, and you will witness something profoundly disturbing; not the expected scenes of medical urgency or healing, but the casual indifference with which human suffering has been transformed into opportunity. For 25 years, this institution has perfected an art form that would make you weep: the systematic conversion of public trust into private profit, wrapped in the sterile gauze of bureaucratic immunity.

The most chilling aspect of Sassoon’s descent is not the magnitude of its corruption, though that magnitude is staggering, but the sheer ordinariness with which extraordinary evil has been normalized. Here, the theft of organs is treated as administrative oversight. The falsification of evidence becomes standard procedure. The extortion of grieving families is filed under “miscellaneous revenue.” What we are witnessing is not merely institutional failure; it is the methodical decomposition of the social contract itself.

Sassoon Hospital- The Architecture of Indifference

To understand how Sassoon Hospital became what it is today, we must first understand the psychological architecture that enables such systematic abuse. This is not a story of sudden moral collapse, but of gradual desensitization; a process by which ordinary people learn to walk past extraordinary suffering with the same emotional detachment they might reserve for checking the weather.

Consider the daily rhythm of corruption that has become as predictable as morning rounds. In 2006, Dr. Kisan Parvati Ubale was caught accepting a mere 2000 rupees for a fitness certificate. 2000; the cost of a modest dinner for a middle-class family. Yet this seemingly trivial bribe represented something far more sinister: the moment when the hospital’s administrators realized that public trust could be monetized without consequence.

The brilliance of this system lies in its incremental nature. Once you have accepted that a fitness certificate can be purchased, the logical framework for selling everything else is already in place. Blood samples can be tampered with for the right price. Disability certificates become commodities. Even the dead can be made to generate revenue through organ trafficking. Each transgression makes the next one seem reasonable by comparison.

Between July 2023 and January 2024, staff of Sassoon hospital did a theft of 4.18 crore rupees from official accounts. This was not a crime of passion or desperation, it was a calculated business operation involving 24 private bank accounts and dozens of conspirators. The precision required for such an operation reveals something deeply disturbing about the institutional culture at Sassoon: theft had become so routine that it required its own administrative infrastructure.

But let us translate these numbers into human terms, because abstract figures allow us to maintain the same emotional distance that enables such crimes in the first place. 4.18 crore represents approximately 15,000 emergency surgeries at government rates. It represents 50,000 blood tests. It represents 2,000 oxygen cylinders. It represents, quite literally, thousands of lives that could have been saved or improved while hospital administrators were busy optimizing their personal portfolios.

The most disturbing aspect of this theft is not its scale, but its timing. This money was stolen during and immediately after the pandemic, when India’s healthcare system was already fractured and bleeding in pain. This is similar to a case where an IAS, Pooja Singhal stole gigantic funds which were kept for people in MGNREGA, the poorest of the poor! While patients died in hospital corridors for lack of oxygen, while families sold their homes to pay for basic medical care, Sassoon’s administrators were perfecting techniques for embezzling public funds with the same methodical precision that should have been applied to saving lives.

Dr. Ajay Taware’s involvement in kidney trafficking displays perhaps the most disgusting and disturbing aspect of Sassoon hospital’s deep rooted corruption. As head of the Forensic Medicine department, Taware held a position of extraordinary public trust. Forensic medicine exists to speak for the dead, to ensure that even in death, truth and justice prevail. When the person charged with this sacred responsibility begins harvesting organs for profit, we have crossed a threshold from which there may be no return.

The kidney trafficking operation reveals the logical endpoint of institutional corruption: human beings reduced to their component parts, each organ assigned a market value, death itself transformed into a business opportunity. This is not merely unethical medical practice; it is the complete abandonment of the philosophical foundations upon which medicine itself rests.

What makes this particularly chilling is the casual efficiency with which such operations were conducted. Organ trafficking requires sophisticated coordination, careful timing, and complete disregard for human dignity. The fact that such operations could be conducted within a government hospital, under the noses of dozens of colleagues, reveals the extent to which moral blindness had become institutionalized and corruption is in plate of everyone, from doctor, to police, to judiciary to politician!

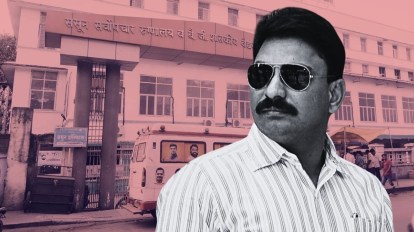

The Porsche crash case of 2024 represents perhaps the most symbolically perfect encapsulation of everything wrong with Sassoon Hospital. Two young IT folks were killed by a minor, or a spoiled rich brat from a politically connected family. In any functional society, this would represent a straightforward case of vehicular homicide, with forensic evidence playing a crucial role in ensuring justice.

Instead, Sassoon Hospital became the site of an elaborate conspiracy to subvert justice. Blood samples were tampered with, alcohol traces were removed, evidence was falsified. Dr. Ajay Taware and Dr. Shrihari Halnor were arrested for their roles in this conspiracy, while Dean Dr. Vinayak Kale was sent on compulsory leave; a punishment roughly equivalent to giving a serial killer a stern talking-to.

The profound cynicism of this operation cannot be overstated. Hospital staff took the blood of mother and used it to protect her son from the consequences of his actions. They transformed a mother’s love into an instrument of injustice. They took the most sacred aspects of human relationships, family bonds, parental protection, medical care, and weaponized them against the very concept of truth itself.

What emerges from this case is not merely corruption, but a complete inversion of moral categories. The hospital, which should serve as a sanctuary for healing, became an instrument of deception. Doctors, who should preserve life and seek truth, became accomplices to murder. The blood that should have provided evidence for justice was replaced with blood drawn from love itself.

The case of extortion involving a 17-year-old boy reveals perhaps the most psychologically disturbing aspect of Sassoon’s transformation: the complete normalization of predatory behavior toward the most vulnerable. A senior resident doctor demanded 24,500 rupees from the mother of a sick teenager, threatening her when she refused to comply with his payment scheme.

Let us pause to consider the psychological architecture of this crime. A trained medical professional, someone who had taken an oath to “first do no harm,” looked at a desperate mother and saw not a fellow human being in crisis, but a revenue opportunity. The teenager’s illness became leverage. The mother’s love became a weakness to be exploited. The doctor’s position of authority became a weapon.

This is not aberrant behavior by a single corrupt individual; it is the logical outcome of a system that has learned to extract profit from human suffering. When an institution consistently rewards predatory behavior while punishing integrity, it inevitably produces predators.

The most chilling aspect of this extortion is its casual nature. The doctor did not seem to view his demands as particularly unusual or risky. This suggests that such practices had become routine, that the extortion of desperate families had become as normalized as taking vital signs.

The arrest of a physiotherapist for demanding 60,000 rupees in exchange for a disability certificate represents the complete moral bankruptcy of Sassoon’s institutional culture. Disability certification exists to protect society’s most vulnerable members, ensuring they receive the support and accommodations they need to participate in social and economic life.

When hospital staff begin selling disability certificates, they are not merely engaging in fraud; rather they are destroying the social mechanisms designed to protect the powerless, aka the common man of India. They are transforming disability itself into a commodity, creating a marketplace where suffering must be purchased rather than acknowledged.

The psychological cruelty of this crime cannot be overstated. The physiotherapist was asking a disabled person to pay for official recognition of their own suffering. This represents a form of double victimization: first by the condition that created the disability, then by the institutional system that should have provided support.

Recall The case of Lalit Patil, who operated a drug cartel from his “hospital bed” at Sassoon while supposedly serving time at Yerawada jail, reveals the complete breakdown of institutional boundaries.

A hospital became a criminal headquarters. A place of healing became a distribution center for substances that destroy lives. Medical facilities became cover for illegal operations. What is most disturbing about this case is not the individual criminality involved, but the institutional incompetence that made it possible. How does a convicted criminal establish and operate a drug distribution network from a hospital bed? How do dozens of hospital staff members fail to notice ongoing criminal activity in their workplace?

The answer lies in the culture of willful blindness that institutions develop when corruption becomes endemic. When everyone is complicit in something, no one is responsible for anything. When the normal boundaries between legal and illegal, ethical and unethical, have been systematically eroded, everything becomes possible and nothing becomes shocking.

Understanding the rot in Sassoon Hospital is equal to understanding the principles that push us towards institutional corruption. Like any ecosystem, corrupt institutions develop their own internal logic, their own food chains, their own mechanisms for maintaining equilibrium.

At the bottom of this ecosystem are the patients, the primary producers, if you will, whose suffering and desperation generate the raw materials that feed every other level. Their pain becomes profit. Their trust becomes currency. Their desperation becomes leverage.

Above them are the frontline staff, nurses, technicians, junior doctors, who learn to extract small amounts of value from each patient interaction. A few hundred rupees here, a minor favor there, gradually building tolerance for increasingly serious transgressions.

Next come the department heads and administrators, who organize and systematize the extraction process. They create the frameworks that allow individual corruption to become institutional policy. They establish the procedures that transform theft into standard operating practice.

At the top are the political and bureaucratic figures who provide protection and legitimacy to the entire system. They ensure that investigations are delayed, that evidence disappears, that consequences are minimized.

This ecosystem is remarkably stable because each level depends on every other level for its survival. No one can expose the corruption without exposing themselves. No one can reform the system without destroying their own position within it.

What allows ordinary people to participate in such extraordinary evil? The answer lies in understanding how moral boundaries are gradually eroded through a process psychologists call “moral disengagement.”

The first step is moral justification: “Everyone does it.” “The system is already corrupt.” “If I don’t take advantage, someone else will.” These justifications allow individuals to reframe obviously unethical behavior as reasonable responses to unreasonable circumstances.

The second step is euphemistic labeling: theft becomes “unofficial fees,” extortion becomes “processing charges,” evidence tampering becomes “procedural flexibility.” By changing the language, participants can avoid confronting the moral reality of their actions.

The third step is advantageous comparison: “At least we’re not as bad as private hospitals,” “At least we’re not killing people directly,” “At least we’re providing some medical care.” By comparing themselves to even worse examples, participants can maintain a sense of relative virtue.

The fourth step is displacement of responsibility: “I was just following orders,” “This is how the system works,” “I didn’t create these problems.” By diffusing responsibility across the institution, individuals can avoid personal accountability.

The final step is dehumanization of victims: patients become “cases,” families become “complainants,” suffering becomes “medical challenges.” By reducing human beings to administrative categories, participants can avoid empathy and moral connection.

What Is The Cascading Effect of Institutional Failure?

Sassoon Hospital’s corruption creates ripple effects that extend far beyond its walls. When a major public hospital becomes unreliable, the entire healthcare ecosystem suffers. Poor families, who cannot afford private healthcare, are forced to accept substandard or predatory treatment. Middle-class families exhaust their savings trying to avoid public hospitals. Trust in all medical institutions decreases.

The psychological impact on healthcare workers throughout the system is equally devastating. Young doctors and nurses, who enter the profession with genuine desire to help people, quickly learn that idealism is professionally disadvantageous. They learn to accept corruption as inevitable, competence as optional, and cynicism as realistic.

Perhaps most disturbing is the impact on patients and their families. When seeking medical care becomes a process of negotiating bribes, avoiding scams, and protecting yourself from the very people who should be protecting you, the fundamental social contract breaks down. Citizens learn that they cannot trust the institutions designed to serve them.

The most chilling aspect of Sassoon Hospital’s 25 decline is how completely the unthinkable has become routine. Organ trafficking, evidence tampering, systematic theft, extortion of vulnerable families; none of these practices seem to surprise anyone anymore. They have become administrative details, background noise in the daily operations of institutional medicine.

This normalization process is perhaps more dangerous than the corruption itself. When extraordinary evil becomes ordinary business, society loses its capacity for moral outrage. When systematic abuse becomes expected behavior, reform becomes impossible.

The staff at Sassoon Hospital do not see themselves as criminals or monsters. They see themselves as practical people working within a flawed system, making the best of difficult circumstances. This self-perception is both psychologically necessary for them and absolutely terrifying for the rest of us.

Every scandal at Sassoon Hospital represents not just financial theft or professional misconduct, but the destruction of something far more valuable: the social trust that makes civilized society possible. When public institutions become predatory, when help becomes harm, when protection becomes exploitation, the entire foundation of social cooperation collapses.

The ultimate victims are not just the patients who have been directly harmed, but all of us who must live in a society where such institutions exist. We all become a little more cynical, a little more suspicious, a little less willing to trust or be trusted. The corruption of public institutions corrupts the entire public sphere.

Since 2006, Sassoon Hospital has generated an impressive record of scandals: bribery, embezzlement, organ trafficking, evidence tampering, extortion, fraud, criminal conspiracy. Yet the institutional response has been remarkably consistent: a few arrests, some administrative reshuffling, lots of promises, and an inevitable return to business as usual.

This pattern reveals something important about the nature of institutional accountability in contemporary India. Accountability has become theater; a performance designed to create the appearance of consequences without the reality of change. Arrests are made, but convictions are rare. Officials are suspended, but they often return to similar positions. Investigations are announced, but their findings rarely see sunlight.

The mathematics are simple: when the cost of corruption is less than its benefits, corruption will continue. When the probability of punishment is low and the severity of punishment is minimal, rational actors will choose corruption. Sassoon Hospital has learned these lessons well.

Sassoon Hospital is not an aberration; it is a mirror. It reflects the broader transformation of Indian society over the 25 years, the gradual replacement of public service with private opportunity, the systematic conversion of social institutions into revenue streams.

What we see at Sassoon is happening throughout the public sector: schools that exist to generate fees rather than education, police stations that function as protection rackets, courts where justice is auctioned to the highest bidder. Sassoon Hospital is simply a particularly clear example of a much larger phenomenon.

This is why fixing Sassoon Hospital matters far beyond healthcare policy. It represents a test of whether Indian society retains the capacity for institutional reform, whether we can still distinguish between public service and private profit, whether we can recover the moral clarity necessary for genuine democracy.

The question is whether we still possess the social antibodies necessary to fight this infection, or whether we have become so weakened by cynicism and indifference that we can only watch while our institutions consume themselves from within.