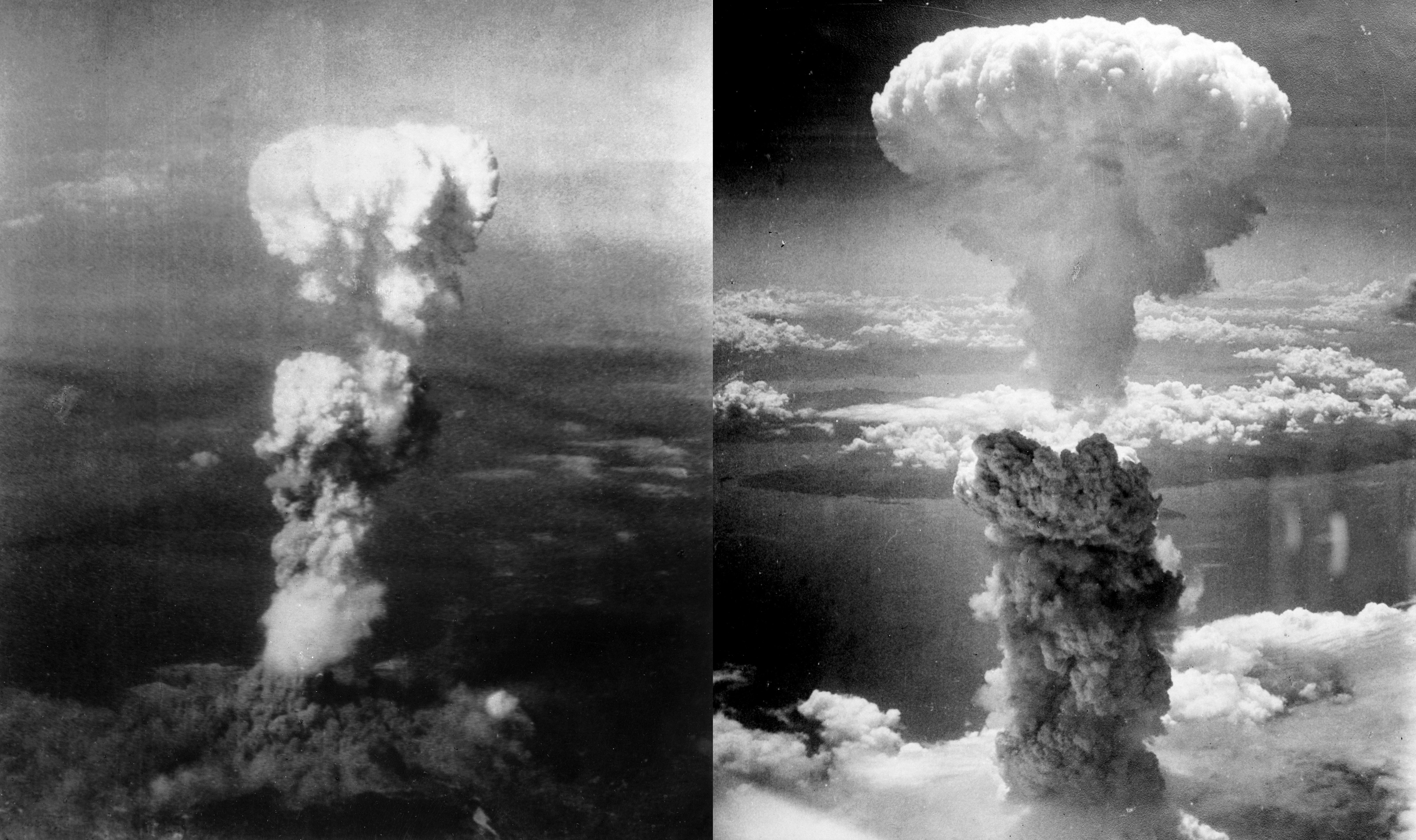

It has been 75 years since two atomic bombs ravaged Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Survivors claim to learn from history in the face of threats from nuclear weapons. In the wake of Beirut port explosion, the capital of Lebanon on Tuesday, we explore the the most devastating explosion in the history.

By the early morning of August 6, 1945, few had been able to rest well in Hiroshima.

The air raid sirens had sounded at least twice. The city of 350,000, built on a river-lined plain and surrounded on three sides by mountains, was tense: it was the only large city, along with Kyoto, that had not yet been bombed by American planes in the throes of the World War II. That it was, its inhabitants feared was a matter of time.

By eight in the morning, its streets were already in a frenzy of activity. The offices and shops had opened, the employees were at their posts. In the centre, about 8,000 high school students demolished entire streets of traditional wooden and tile houses to open a firebreak that would alleviate the worst effects of this bombing.

Koko Tanimoto’s mother, an eight-month-old baby, was holding her daughter, dressed in a small pink robe, before the arrival of a visit home. Outside, Keiko Ogura’s father, an eight-year-old elementary school student, had woken up with a bad feeling. The girl better not go to the school that day. Keiko’s 13-year-old older brother and other classmates were helping, near the mountains north of the city, to harvest potatoes to feed the population. The day, they would later recall, was one of extraordinary clarity.

At 8.15 a.m. a US B-29 escorted by two other planes was flying over the city. The safe siren had just sounded: the operators had interpreted the dots on the radar as a reconnaissance mission. Keiko’s brother looked up at the sky at that exact moment and saw a point detach from the bomber. As he turned around, a blinding light filled everything. The Enola Gay, piloted by Paul Tibbets and with Robert Lewis as co-pilot, had dropped Little Boy, the first atomic bomb in history, and unleashed hell under the mushroom cloud that was beginning to form.

About three meters long and four tons in weight, the bomb that carried 50 kilos of uranium took 43 seconds to drop. Its explosion at about 580 meters above the city centre caused a fireball 28 meters in diameter and a temperature of 30,000 degrees Celsius. The force of the blast collapsed buildings, trapped thousands of people under rubble, dumped bodies in grotesque positions.

The heat cast permanent shadows on the little that was left standing, melted eyes and skin; fires started. Many survivors would speak after rivers full of floating corpses; of voices beneath the ruins that begged for help as the flames approached; of floods of ghostly-looking wounded, some with their eyes on their hands, others with their arms raised so that their tattered skin would not touch the ground.

70,000 people died immediately, including 3,600 of the schoolchildren demolishing homes. Another 70,000 would die before the end of the year, from their injuries or from radiation. Until August 2019 there were 319,816 deaths over the years as a result of that bomb and the one that the US Air Force would drop three days later, on August 9, 1945, in Nagasaki.

“Water water!”

A mile from the hypocenter, the Tanimoto family’s house had completely collapsed on little Koko and her mother. “Over time, my mother told me that she spent a while semi-conscious. She heard a baby cry, it sounded very far away. Finally, she realised that it was me who was crying. I was under her and I was suffocating, she was trapped in the rubble.

She dug through the rubble as best he could, orienting herself by a line of clarity, to get us out “, explains by phone from her home in Japan Koko, now 75 years old and with the surname Kondo, that of her husband.

In the street, complete darkness: the cloud from the bomb had turned the bright day into the dark night. Mother and daughter, miraculously unharmed, would manage to get out of the ruins of their house just in time: the fire, fuelled by the wood of the buildings, was already approaching.

It would even jump over rivers and, due to its extreme virulence, unleash a very strong wind.Outside, the shock wave from the blast had knocked Keiko Ogura, who was playing in the garden, to the ground, knocking her unconscious. Upon awakening, a shed in front of her was on fire. There were tiles and rubble everywhere.

Almost groping, in the dark, she entered her house, standing but without a roof. Her brother, with burns, ran in. “From the field where I was, I had seen that Hiroshima had been completely destroyed. That fire had started. And that a river of injured people came from the centre to the area where we were, where there was a shrine,” Ogura recalls in a videoconference organised by the Foreign Press Center of Japan.

Looking out into the street again, little Keiko saw a Dantesque sight. “Many people! With terrible wounds and burns, with singed hair, disfigured, with skin that slipped in shreds from their hands. They huddled on the floor, sprawled on the stone stairs to go up to our house. Nobody said anything, only moans and the words ‘Mizu, mizu‘ (water, water) could be heard ”.

“I started to bring them water from the well. Some, while drinking, simply fell dead. Later they told me that the wounded should not be given water, but then I was horrified. I thought I had killed them. I had nightmares for a decade” he recalls.

The fire took three days to burn out and was stopped a short distance from his home. But the heat it generated unleashed a hurricane wind first. Then came a radioactive fallout, of abnormally large drops, the “black rain”. “The next day was awesome. Simply, Hiroshima had volatilised” recalls Ogura. Twelve square kilometres of the city had been completely razed. 70% of the buildings had collapsed.

The vast majority of the victims died without any help: 90% of the medical personnel had died or were too seriously ill to work; 42 of the 45 hospitals in the city had been completely destroyed. “For days and days, the only thing that could be done was to incinerate the dead. My father helped with the ceremonies that were held in a park near my house. About 700 bodies were buried there, ” explains the hibakusha, as the survivors of the bomb are known in Japanese.

Three days later, on August 9 at 11:02 a.m., another B-29, Bockscar, dropped another bomb, this time of plutonium, at Nagasaki. That city was not the original target: the attack was planned against Kokura, where the Japanese troops kept a large arsenal. But the sky over that town was cloudy, and the bomber crew opted for the second on the list.

Fat Man, as it was called, generated a much larger blast wave – equivalent to 22,000 tons of trilite, compared to 15,000 for Little Boy – but the bomb did not fall in the centre of the city, but in an industrial suburb; the mountains offered some protection against impact. Still, 40,000 people perished then, 30,000 more before the year was out. Another 75,000 were injured, tens of thousands with sequelae that still drag today. A third part of the city was devastated.

“That bomb not only claimed lives, decimated families and caused enormous destruction,” explains current Nagasaki mayor Tomihisa Taue, in a talk with foreign journalists. “It also left deep wounds on the bodies and minds of those who survived.”

“That second demonstration of the power of the atomic bomb apparently caused panic in Tokyo, since the following morning brought the first indications that the Japanese empire was ready to surrender,” wrote US President Harry Truman in his memoirs. On August 15, the Japanese heard for the first time on the radio the voice of their tenno, their emperor: Japan capitulated. The surrender would be signed on September 2. The war was over.

But hell was not over for the victims: the radiation would take tens of thousands more people before the end of the year, leaving tens of thousands with consequences. A medical student – the only care they could have – recommended to Koko’s parents that they prepare to lose their daughter, a victim of severe diarrhoea. “Fortunately, I got over them,” she laughs now.

His first memory: “He was two or three years old. My father was a Protestant reverend (his story is told in Hiroshima, by the journalist John Hersey, who in 1946 told the world about the consequences of the bomb) and many orphans, street children, came to the parish.

They treated me like their little sister. Many could not see their faces, they were disfigured. I had no memory of the bomb, I knew something terrible had happened but also that I shouldn’t ask. One day one of these girls was combing my hair. I turned to look at her, wanted to see how she did it. The girl had the fingers of her hands fused together ”.

So it was common not to talk about what had happened. Many hibakushas did not want to declare themselves as such: for decades they faced discrimination from their fellow citizens and the stigma of having experienced radiation.

It was difficult for them to find work because of its aftermath and many families refused to allow their children to marry survivors, for fear that their descendants would be born with congenital problems. “We ourselves had this fear, but we could not talk about it. It’s a kind of trauma, ”says Ogura, who had two children.

Kondo says he discovered that it was all due to the bomb from the conversations he heard from the orphans. “As a child, she had a deep hatred for those who had cast her. I promised myself that when I was older I would look for the culprits and beat them, bite them and spit on them ”.

Face to face between the co-pilot of the ‘Enola Gay’ and his victims

On May 25, 1955, when she was 10 years old, Koko’s way of thinking took a drastic turn: “I will never forget it,” she emphasizes. The American occupation of Japan had ended three years ago. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were advancing in their reconstruction.

Her father, famous in the United States for his role in Hersey’s book and for his campaign to obtain treatment in that country for girls disfigured by the bomb, appeared that day on the television program This is Your Life. The whole family had travelled to the studios to participate in that live recording, without knowing who the rest of the guests were.

“I knew most of the people on the set, but there was one man I had never seen before. I asked my mother who it was, and she hesitated. I didn’t know how I was going to react, ”explains Kondo. “She finally told me. It was Robert Lewis, the co-pilot of the Enola Gay ”.

“I was petrified. I wanted to hurt him, but I knew that in the middle of filming I couldn’t go after him. And then they asked him what he felt that day. I saw tears in his eyes when he recounted what he had written in the log. I was startled: I realised that this man was not the monster I had imagined; he was a human being ”.

“Without the cameras seeing us, I touched her hand: it was my way of offering forgiveness. He grabbed mine very hard” he continues. “At that moment I learned one thing: if I am to hate something, it must not be a specific person. I just hate the war itself ”.

Goodbye to the weapons?

Many hibakusha have dedicated their lives to activism for victims and against nuclear weapons. The Korean War (1950-53) and the United States’ nuclear tests in the Pacific forced them to reflect that their own suffering had not been enough to convince the world of the need to abolish this weapon and that they should then disclose their experiences to avoid any temptation to use the pump in the future, explains Ogura.

She herself has founded the NGO Interpreters of Hiroshima for Peace, which helps to spread what happened in August 1945 and the anti-nuclear message to foreign tourists visiting Hiroshima.

In the case of Kondo, who for years did not want to identify herself as a survivor, a long process of listening to her father’s experiences finally convinced her to follow in the footsteps of the reverend in his aid campaigns; He is currently collaborating with ICAN, the International Campaign for the Abolition of Nuclear Weapons, which in 2017 won the Nobel Peace Prize.

“It is not easy to achieve change, but little by little, transmitting the message from person to person, one day we will achieve it. This is what my father told me, and my sincere hope” says Kondo. The mayor of Nagasaki agrees. “If a third nuclear bomb has not been dropped in these 75 years, it has been largely due to the efforts of the hibakusha, their contribution in making known the stories of what happened under the atomic cloud,” he says.

His city proposes the creation of a “nuclear-weapon-free zone” in Northeast Asia, including North Korea, South Korea and Japan (the latter two countries are currently protected by the US nuclear umbrella). “We know it will take time, but the goal is worth it,” explains Taue.

Time is short. The average age of the 130,000 hibakushas alive, 75 years after the bombs, is 83 years. A survey published by the Asahi Shimbun newspaper found that, although 86.9% of those over the age of 80 still clearly remember what happened that August 6, that proportion falls to 14.8% among survivors in their 70s. Among the hibakusha of that age, 44.8% confessed not having any memory of the bomb.

Regardless of their age, most view with concern the limited progress made in eliminating nuclear weapons. From the campaign launched for this purpose by US President Barack Obama during his tenure, only a few months remain until the New START treaty between the United States and Russia expires in February 2021. 62.1% of The Hibakusha believe that in the last five years the risk of a nuclear bomb being used again somewhere in the world has increased.

The only positive development since then has been the approval, in July 2017, of the UN Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. But for its entry into force, the signature of 50 countries is necessary. So far only 40 have subscribed; Japan is not even among them, since it enjoys US nuclear protection. The government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, which offers itself as a bridge between the nuclear countries and those that are not, considers that a ban is still “premature”, to the discomfort of the survivors.

“We get older and we don’t know when our time will come when we will meet our relatives in the afterlife. That is why we want to see nuclear weapons eliminated while we are alive”, explains Ogura. His voice shaking with emotion, he adds: “We want to be able to tell you that we made it. It is something that I wish and for which I pray every day: to eliminate nuclear weapons as soon as possible so that I can tell it to those who died in vain because of the bomb.